Does possessing enough nuclear weaponry to make great power wars the potential cause of humanity’s extermination make such wars obsolete? Unfortunately, history tells us that, far from being obsolete, such wars may be unavoidable, and they grow in likelihood as the competitive international environment becomes increasingly militarized. A better question might be to ask if future wars can be fought below the level in which one side feels compelled to initiate an extinction event. Here, there is room for some optimism: History is replete with examples of great powers fighting prolonged, near-total wars but maintaining them below the existential level, in which one side is utterly ruined and the other is often little better off.

As Rod Lyon has written:

Is a great-power war between [the United States] and China possible? I think we could answer that question directly: possible, yes; likely, no. Great powers, especially nuclear-armed ones, don’t go to war with each other lightly. But sometimes wars happen. And they aren’t accidents. They’re about international order . . . and the life and death of states. And the principal reason for fighting them is that not doing so looks like a worse alternative.1

If a great power war does break out, the single overarching strategic imperative is to keep the conflict below the threshold in which one side views risking a world-destroying nuclear exchange as conceptually viable. The most crucial factor in achieving this outcome is that each party entering a conflict seeks only objectives it can walk away from without facing further catastrophic impacts. Several centuries ago, the European great powers discovered how to manage this existential problem, and their basic concepts likely could help prevent a war today among great powers from becoming one of annihilation. Still, given the possibility—some would claim probability—that any great power conflict will escalate into the nuclear arena, policy-makers should always view a military conflict as something best avoided.

Cabinet Wars: The Advent of an Idea

One solution can be found in what the Germans called Kabinettskrieges—“cabinet wars”—which flourished in the wake of the unconstrained bloodletting and destruction of the Thirty Years’ War. That conflict, which left much of Central Europe ruined and its population decimated, was a wake-up call for rulers within the nascent state system rapidly taking root. The war ended in the Treaty of Westphalia, which remade the European international order. But even in this new system, the most powerful European states did not give up their expansionary ambitions, and those not looking to expand were kept busy defending their territory from those that did. In short, European powers never lacked reasons to go to war. What changed was that states were shifting their aims from total victory and subjugation of the loser to more limited objectives, such as seizing a coveted province or colony.

In fact, this shift was coming into view long before the Treaty of Westphalia was negotiated. For example, Sweden’s King Gustavus Adolphus was just as interested in securing the Baltic, and turning it into a Swedish lake, as he was in destroying Catholicism within the Holy Roman Empire.2 By 1635, the war had lost so much of its religious dimension that Armand Jean du Plessis—better known as Cardinal Richelieu—felt free to bring Louis XIII’s overwhelmingly Catholic France into the war on the Protestant side for raisons d’etat (“reasons of state”)—primarily, limiting the growing power of the (Catholic) Hapsburg Empire.3 But Richelieu was never interested in the much larger aim of destroying the Hapsburg Empire; a goal that certainly would have been the ultimate, if unachievable, objective of earlier rulers.

Cabinet Wars in Modern History

Propelled in no small way by the horrors unleashed by the marauding religiously inspired armies of the Reformation era, rulers, generals, and the educated elites who advised them made sustained and serious attempts to professionalize their armies and regulate warfare. It was the Age of Enlightenment, and although civilians still suffered appalling ordeals wherever armies tread and atrocities took place frequently enough as to be considered unremarkable, states and militaries made huge strides in reducing the impact of war on wider society.

Professional armies even began paying more than lip service to concepts such as extending the rule of law to the battlefield, and books such as Hugo Grotius’s The Rights of War and Peace were garnering huge numbers of readers.4 Moreover, as military forces became more professional, they systematized their logistical operations, making it possible for armies to sustain themselves without ravaging the countryside—though that remained an oft-used emergency option. However, the most crucial factor in limiting the effects of war on engaged societies was that conflicts were now mostly fought for specific and limited political objectives—reasons of state.

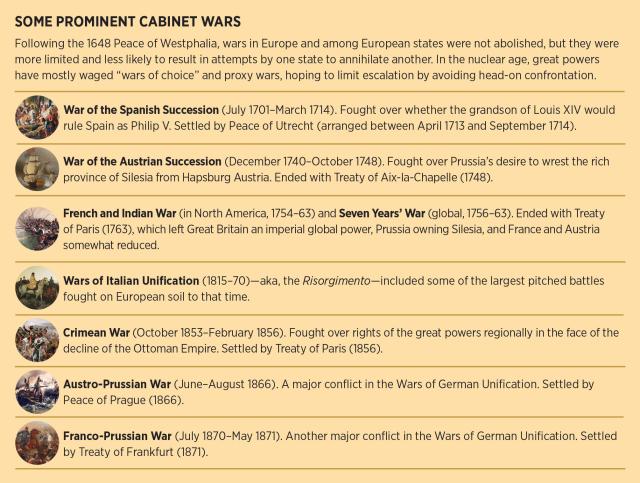

This political overlay typically set what appeared to be an attainable objective, such as seizure of a province or domination of a lucrative trade route, which, once attained, would lead to the war’s rapid conclusion. Such limited objectives made it possible to plan for war termination short of one side or the other being completely vanquished. In Clausewitzian terms, warfare no longer drove toward the absolute.5 In short, wars became more regulated, were fought over lesser stakes, and—most crucial—could end short of mutual ruination. Nonetheless, examples on the timeline on the next page show that even “limited” cabinet wars easily reach intensities requiring extraordinary mobilizations of military and economic resources.

While these wars never became absolute wars in the sense that nations were not conquered, left in complete ruin, or depopulated by military atrocities or famine, they were, nevertheless, total wars. Each was fought on a global scale and called on the warring states to undertake unprecedented mobilizations of their military, financial, and other resources. In their wake, virtually every European nation faced bankruptcy and suffered from hugely increased levels of internal instability, which would soon boil over into what historian Eric Hobsbawm named The Age of Revolution. As defined by their causes and how they ended, these wars were indeed limited. But, in the 150 years after Westphalia, “limited” was not synonymous with small, lacking intensity, or inexpensive. The “limited” conflicts of the future likely will be similarly costly in blood and treasure.

Historians often credit the French Revolution and particularly the Napoleonic method of war with ending the era of limited warfare. Certainly, by introducing the Levée en Masse, France replaced the cabinet wars of the previous century with wars of the people, in which a state’s entire population was mobilized for war.6 By tapping into newly burgeoning waves of nationalism, these “people’s wars” (Volkskrieger) were fought with extraordinary resolve and rarely ended short of the conquest and subjugation of one of the contestants.7 It was this new version of total war that became the model for Clausewitz, and, unfortunately, the driving dynamic for the great wars of the 20th century. In this new—some might say restored—paradigm, wars no longer were fought over such trifles as a province or a colony; rather, the stakes were elevated to national survival.

The Napoleonic era only ended when the Allied armies finally overran France in 1814 and then again in 1815. For nearly a century afterward, the Concert of Europe was able to put the genie back in the bottle. Still, while the Concert did an adequate job keeping the great powers from engaging in one another’s spheres of interest, it did little to limit any power’s actions within its respective sphere. Thus, Russia acted as it pleased throughout Central Asia, while Great Britain did as it wished in South Asia and, joined by France, did much the same in Africa. Moreover, the Concert’s framework, though adequate for stopping the great powers from engulfing Europe in the flames of war, was incapable of halting all European conflicts—opening the way to a renewed bout of cabinet wars.

Two such wars set the standard for how strategists think about them: the Austro-Prussian War (1866) and the Franco-Prussian War (1871). In each, the brilliant Prussian Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, deftly outmaneuvered Prussia’s enemies, leaving them diplomatically isolated and easy prey for Helmuth von Moltke’s brutally efficient Prussian Army. Still, in the wake of Moltke’s decisive 1866 victory at Königgrätz, it took all of Bismarck’s influence and political guile to restrain the generals from marching on Vienna—a huge enlargement of the war’s objectives that would surely have forced Austria to continue the struggle to a much bloodier end.8

Nor did Prussia’s war against France go entirely as planned. Although the Prussian Army almost effortlessly captured France’s two field armies in the 1870 battles at Metz and Sedan, the war did not end. Instead, France undertook a yearlong fight that threatened to become a Volkskrieg, as new armies were raised south of the Loire River. It was only with some difficulty that Bismarck was able to negotiate an end to the conflict in 1871.9

In the years after the war, Moltke gave considerable thought to what a return of the concept Volkskrieg meant for the future of conflict, particularly when it was coupled with the Industrial Revolution’s impact on the changing character of war. In his final appearance before the Reichstag, in 1890, Moltke warned:

The age of cabinet war is behind us—all we have now is people’s war. . . . Gentlemen, if the war that has been hanging over our heads now for more than ten years like the Sword of Damocles—if this war breaks out, then its duration and end will be unforeseeable. The greatest powers of Europe, armed as never before, will be going to battle with each other; not one of them can be crushed so completely in one or two campaigns that it will admit defeat, be compelled to conclude peace on hard terms, and will not come back, even if it is a year later, to renew the struggle. Gentlemen, it may be a war of seven years or thirty years duration—and woe to him who sets Europe alight, who first puts the fuse to the powder keg.10

The 20th century’s two world wars stand as evidence of Moltke’s foresight.

The Return of Cabinet Wars

The past 70 years have provided numerous examples of conflicts in which great powers have engaged in what are now commonly called “wars of choice.”11 For the United States, a list of such conflicts includes Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Russia waged similar wars of choice in Afghanistan in the 1980s and Georgia in 2008—and in Ukraine today. China has fought such wars against India (1962) and Vietnam (1979). Still, since 1945, the great powers have not squared off directly against one another. In fact, many analysts believe such a conflict is impossible, as—when weighed against the risk of nuclear Armageddon—any possible objective pales to insignificance.12 That leaves strategists and policymakers with a question: Will any great power ever initiate or allow itself to be drawn into a war against another great power?

Given the multiple stresses within the international system, and the increasing militarization of many of them—the South China Sea, Taiwan, the Baltic states, Ukraine, Korea, Syria—the possibility of a great power war cannot be discounted. Still, no sane leader believes any of these points of confrontation are worth a strategic nuclear exchange. Moreover, few people believe the United States will risk thermonuclear war to maintain Taiwan’s or the Baltic states’ independence. Still, it remains widely accepted that the United States will fight a conventional struggle for either of these objectives, as well as for other vital interests. If it did, what would such a war look like?

During the Cold War, the United States developed an entire strategic vocabulary to think about and discuss this problem. Then, every strategist was steeped in the ideas and theories of “flexible response.” While the topic was typically discussed in terms of nuclear options, the flexible response concept was sustained through the maintenance of huge amounts of NATO’s conventional power, capable of stopping a Soviet attack without having to resort to nuclear weapons. At the height of the Cold War, in the 1980s, NATO’s leaders were hopeful a conventional Soviet attack could be blunted, and peace negotiated, without ending the world. Any such conflict was likely to be prolonged, costly, and involve the mobilization of huge portions of the U.S. and NATO conventional military forces. But if peace could be negotiated before the silos opened—the Clausewitzian absolute—the war could remain limited.

This is the essence of a cabinet war. It leaves one to wonder when and why so many current strategists abandoned the notion of limited war remaining viable. Certainly, the possibility of a great state war is no less likely than it was during the Cold War, and it must be prepared for with the same care Cold War strategists employed to reduce the risk of nuclear escalation.

In any future great power war, it might be helpful to think of objectives such as Taiwan or the Baltics as small territories that are in one camp but are coveted by another great power, like provinces in an 18th-century cabinet war. One side is willing to fight to keep the province (state) within its sphere, while the other side is willing to fight to take it. Neither great state, however, is willing to see itself destroyed or its internal political order overthrown to attain its objective. This is a recipe for a future “cabinet war” that would be horrifically costly in blood and treasure. At the very least, such a conflict is far from unimaginable and, given the trajectory of the world’s current great state competitions, it should be considered probable.

Avoiding Cabinet Wars

How can tomorrow’s cabinet war be avoided? The answer is both simple and expensive. As during the Cold War, the United States and its allies must find the funds to pay for large and capable conventional forces, ones capable of intimidating other great state competitors. As it has always been, the best way to deter an enemy from making a grab at a friendly “province” remains convincing adversaries that the likely result will be catastrophic for their forces and any ill-gotten gains eventually will have to be surrendered. At the same time, the United States must fund a modernized nuclear arsenal, large enough to guarantee an overwhelming second-strike capability to ensure the United States cannot be blackmailed into accepting an international fait accompli. Finally, the United States must telegraph its intentions and redlines to the world, both to assure allies and to keep foes from gravely miscalculating. And if war still breaks out, every nation must understand where the others’ conventional and nuclear firebreaks are. This, coupled with an established and internationally integrated crisis management procedure, will be crucial in terminating a conflict short of Armageddon.

In sum, strategists need to think long and hard about how the United States will fight a prolonged war against another great power that can—and surely will—become “total” without becoming “absolute.” Moreover, they will have to put just as much consideration into ideas for war termination as they do for planning the fight, and then find ways to put these termination efforts into effect even as conflict rages without a clear victor.

1. Rod Lyon, “Is Major War Obsolete?” The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 19 August 2014.

2. Cam Rea, “‘Lion of the North’ Gustavus Adolphus and the Thirty Years’ War: Fighting the Holy Roman Empire—Part I,” War and Civilization blog, www.camrea.org, 18 January 2017.

3. Iskander Rehman, “Raison d’Etat: Richelieu’s Grand Strategy During the Thirty Years’ War,” Texas National Security Review 2, no. 3 (June 2019).

4. Hugo Grotius, The Rights of War and Peace (1901 ed.), oll.libertyfund.org/titles/grotius-the-rights-of-war-and-peace-1901-ed.

5. Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Michael Howard and Peter Paret, eds. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), 8.

6. Paul Halsall, “Levee en Masse,” Modern History Sourcebook.

7. Mark Hewitson, “Princes’ Wars, Wars of the People, or Total War? Mass Armies and the Question of a Military Revolution in Germany, 1792–1815,” War in History 20, no. 4 (November 2013): 452–90.

8. Rea, “‘Lion of the North’ Gustavus Adolphus.”

9. Stig Förster, “Facing ‘People’s War’: Moltke the Elder and Germany’s Military Options after 1871,” Journal of Strategic Studies 10, no. 2 (October 1987): 209–30.

10. Quoted in Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War: Explaining World War I (New York: Basic Books, 2008).

11. Rod Lyon, “Wars of Necessity, Wars of Choice,” The Strategist, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 26 April 2017.

12. Graham Allison, “The New Spheres of Influence,” Foreign Affairs 99, no. 2 (March/April 2020).