“DIVEST TO INVEST” continues to be heavy on the divestment side of the equation. The Department of the Navy’s fiscal year (FY) 2023 Budget Highlights Book, released in April, has revealed plans to eliminate a number of Navy expeditionary aircraft squadrons over the next two fiscal years, while also dropping the RQ-21 Blackjack unmanned aerial system from the Marine Corps.

If the plan survives review by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Department of Defense, and Congress. inFY2024, the Navy will begin sending all five expeditionary electronic attack (VAQ) squadrons to the Boneyard at Davis Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona. The plan will remove 1,020 officer and enlisted billets and see 25 EA-18G Growlers mothballed. These expeditionary squadrons are not attached to carrier air wings, but instead support combatant commander requests from land bases

The five squadrons to be shuttered— VAQ-131, -132, -134, -135, and -138- are based at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Washington. The report anticipates Future Years Defense Plan savings of $807 million.

In addition. Highlights reveals the Navy’s plan to sundown its only reserve hehcopter sea combat (HSC) squadron, HSC-85. The Firehawks of HSC-85 also are the service’s only squadron that primarily supports Naval Special Warfare.

Navy SEALs often rely on other services for transport, especially the Army ’s 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (the Night Stalkers), but this decision would leave the Navy without dedicated aviation support for its own special operations forces—a curious decision given recent calls for SEALs to return to their naval roots.

This is the second time in recent years the Navy has tried to eliminate the squadron. Navy Times reported in January 2016 on the Navy’s proposed shuttering of HSC-85 even as the unit was deployed overseas. HSC-84, a second Navy Reserve special operations support squadron, was inactivated at that time. Closing HSC-85 is expected to save $21.6 million in FY2023 and $312.5 million in future years.

For the Marine Corps, Highlights notes unsentimentally that:

The RQ-21A does not meet the capabilities required to support the Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations and Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment Concepts, and is no longer operationally relevant. Divestment will be complete by FY2025.

It predicts FY2023 savings of $7.8 million, and a total of $108.3 million in future years.

DDG(X) Moving Forward

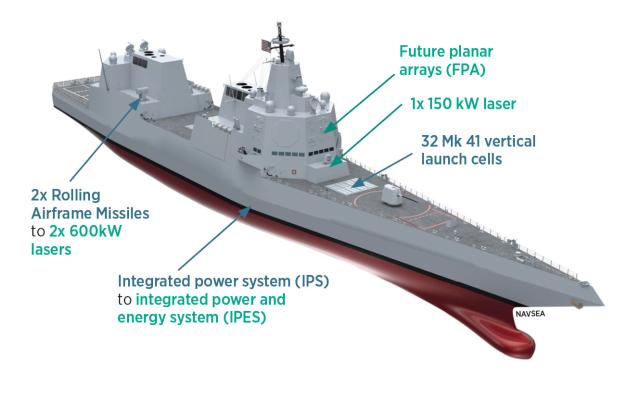

IF THE USS ZUMWALT (DDG-1000) and the Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) had a very ugly baby, it would probably look very much like the notional image the Navy released of tire DDG(X) Next-Generation Destroyer concept at January’s Surface Navy Association National Symposium. A Congressional Research Service (CRS) “in focus” briefing, released on 26 April, gives some details about current development and plans.

CRS says the Navy anticipates a displacement between the 9,700 tons of Flight III DDG-51 destroyers and the DDG-1000’s 15,700 tons. At the outset, DDG(X) will employ a proven combat system—that of the DDG-51 Flight Ills—to reduce program risk.

This will help offset risks created by the new technologies planned for DDG(X). For example, the ship will eventually incorporate a new integrated power and energy system (IPES) that draws on lessons from the challenging development of the Zumwalt-class destroyers and the Columbia-class ballistic-missile submarines.

On most conventionally powered Navy ships today, some of the ship’s engines (usually gas turbines) are dedicated to powering a physical transmission that turns the screws, while others (typically diesel engines) generate electricity for computers, sensors, ventilation, etc. In general, if one set of engines is offline, the other set can do little or nothing to power systems attached to it.

The Zumwalt and its integrated power system were supposed to change that. Any Star Trek fan is familiar with starship captains demanding “more power” from their engineers or directing that power be diverted with ease from one system to another in an emergency. By switching from a mechanical transmission to electric-drive propellers and generating all-electric power with its engines, the Zumwalt was supposed to be able to move power seamlessly from low-demand to high-demand systems. A variety of problems have reduced the integrated system’s utility, however.

But for DDG(X), the Navy needs to figure it out quickly. As the illustration shows, the Navy plans to incorporate a variety of medium- and high-power lasers (and perhaps other directed-energy weapons) on the design while improving fuel efficiency and increasing range and on-station time. Achieving these ambitious goals will require getting the electric destroyer’s power system right.

The Navy anticipates beginning construction on the first DDG(X) in 2030.

proposed weapons and sensors for the DDG(X). Items in blue are intended

for the baseline, while items in green might be added on later iterations. Credit: NAVSEA

1. Ronald O’Rourke, “In Focus: Navy DDG(X) Next-Generation Destroyer Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, 26 April 2022.

A Commercial Heavy Icebreaker For The Coast Guard?

IN ITS FY2023 BUDGET REQUEST, the Coast Guard asked Congress for $125 million to purchase a commercial polar ice breaker. In early May, the Department of Homeland Security (the Coast Guard’s parent agency) released a formal request for information from potential vendors, according to The Maritime Executive.

With the service’s Polar Security Cutter heavy icebreaker program moving at a glacial pace, the notion of obtaining an existing icebreaker as an interim step first appeared on the Coast Guard's FY2022 unfunded priorities list. The first Polar Security Cutter is now expected from builder VT Halter in FY2026, and the second (of a planned three) has been ordered. According to Arctic Today, the Coast Guard has identified the Aiviq, an "ice-hardened tug supply vessel built by Edison Chouet in 2012 for $200 million" as “the most likely candidate.”

With an expected refit time of 18 to 24 months, the proposed interim solution could give the Coast Guard a comparatively new heavy icebreaker in the Arctic several years ahead of what seemed possible just a year ago. The service's only heavy icebreakers at present, the USCGC Polar Star (WAGB-10) and Polar Sea (WAGB-11), were commissioned in 1976 and 1977, respectively.