Naval officer retention is a pressing issue. A good job market, flat defense budgets, and high operational tempo have led many officers to leave the service, which, in turn, has led the Navy to offer large bonuses to encourage more officers to stay. What if the focus were shifted from bonuses to how officers are assigned to their communities?

The culmination of four years at the Naval Academy or in NROTC is an event often referred to as “service selection.” Midshipmen who do not get their top choices, however, are reminded that the process actually is “service assignment,” and the “needs of the Navy” are the primary factor in the outcome. In 2020, 81.7 percent of the Academy graduating class received their top choice, the lowest percentage in the previous five years, which averaged about 88 percent.1 Compare this with the West Point class of 2020 results, which saw 88 percent of cadets receiving their first choice, an 11 percent increase over the previous year.2 How can the Navy expect to retain officers who lose out under this system?

According to Naval Academy director of professional development Captain William Switzer, filling nuclear billets is the hardest and probably the “least-liked part of the process.”3 Nuke draftees likely would concur with this assessment. The Navy actually has an excess of female officers interested in becoming submariners, but limited billets prevent the optimal placement of personnel.4 However, changes in the service assignment process must go beyond the gender balance of the submarine community. There are some possible solutions.

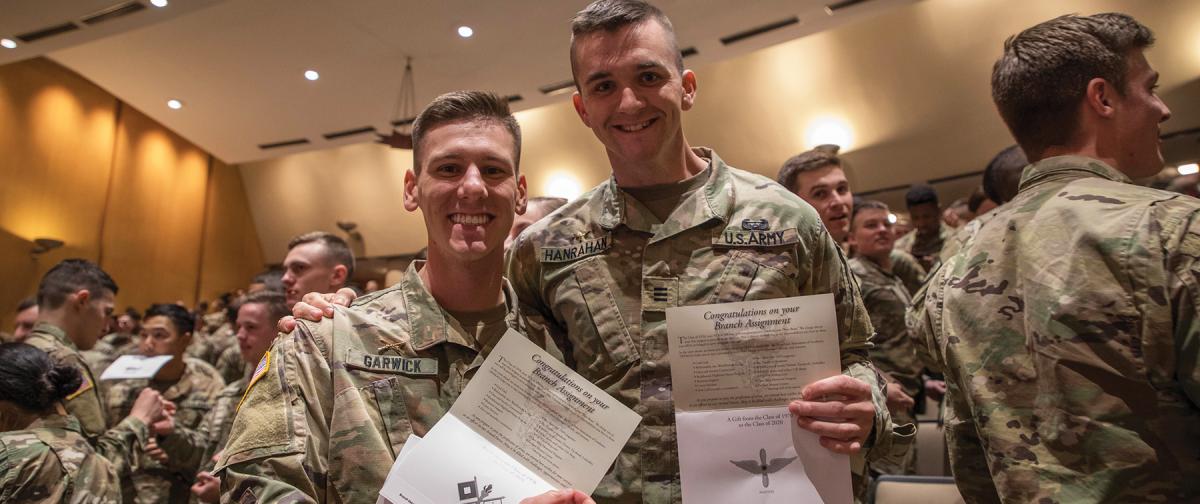

The improved outcome at West Point was a direct result of an overhaul of its assignment system, with the stated intent of improving retention and job satisfaction. The new Market Model Branching System is highly collaborative and transparent. Cadets have an opportunity to interview with the various Army branches so they are better informed regarding the life and duties of an officer in a given branch. In addition, the system not only considers cadet preferences, but also allows each branch to rank cadets. Cadets can see how the branches ranked them—as well as the results of a simulation that shows where they would have been placed—before finalizing their preferences.5 They can then move a branch up or down in priority based on their chances of receiving it.

Opening the service assignment process for midshipmen and communities to have a dialogue about the desires of the former and the needs of the latter is an important change that needs to be made.

The current Navy process also requires a structural alteration, and the Army has a solution for that as well. The Navy should offer a version of the Army’s Branch of Choice Active Duty Service Obligation, in which cadets commit to serving three extra years if selected for their desired branch. Through this program, the Army gets an extended service commitment and the cadets increase their chances of getting their desired branch.6

For many junior officers, the decision to serve beyond their initial commitment largely rests on job satisfaction, not monetary incentives, as bonuses will seldom match private-sector alternatives. If a midshipman is motivated to join a particular community, granting him or her a spot in exchange for extra years of service is a win-win solution. The Navy should follow the Army’s lead and improve officer retention, not by throwing money at the problem, but by working with midshipmen.

1. Selene San Felice, “Naval Academy Service Assignments: What Are the Odds Midshipmen Get Their First Choice and What Does It Take?” Capital Gazette, 27 November 2019.

2. Brandon O’Connor, “West Point Grads Get Assignments through New Branching System,” Army.mil, 18 November 2019.

3. San Felice, “Naval Academy Service Assignments.”

4. Ben Werner, “Submarine Community Can’t Meet Demand from Female Sailors,” USNI News, 11 November 2019.

5. O’Connor, “West Point Grads.”

6. Kyle Rempfer, “West Point Has Changed How Cadets Are Assigned Branches—ROTC Will Soon Follow,” Army Times, 13 September 2019.