The mission of the Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) is to deliver timely, effective, and sustainable naval aviation capabilities to ensure warfighter mission success and safe return. As the technical and acquisition arm of the Naval Aviation Enterprise (NAE), NAVAIR directly supports the Commander, Naval Air Forces (the Air Boss), and the Marine Corps’ Deputy Commandant for Aviation (DCA). In the fall of 2018, leaders at NAVAIR began redesigning the organizational structure and operating concepts to better accomplish this critical mission.

Prior to the restructure, numerous initiatives to increase speed and improve readiness were simply not “moving the needles” in terms of fleet outcomes. Additionally, the command was slow to recognize emerging problems and opportunities, and reallocate resources when required. Good intentions could not overcome organizational inertia, and Navy and Marine Corps major commanders—acquisition program managers, fleet readiness centers (FRCs), fleet type wings, and Marine Air Groups—were not getting the support needed to deliver, operate and sustain capabilities.

With research from outside of traditional lifelines, and input from across the command, we designed an organizational structure to maximize NAVAIR’s warfighting value and increase responsiveness to program and fleet needs. We also set a goal to support readiness and increase speed while reducing the cost of operations by consolidating redundant functions. Throughout the redesign, there was great interest and support from resource sponsors and fleet leaders. In addition, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition designated NAVAIR’s redesign as one of the department’s “Bold Moves” for 2019.

The resulting organizational structure better suits our mission responsibilities with foundational elements including integration of functional disciplines, significantly increased empowerment and delegation, and a more adaptive culture to deal with new circumstances and opportunities. NAVAIR’s new “Concept of Operations for the Mission-Aligned Organization” was released on 1 June 2020 and continues to be periodically assessed and refined.

The new CONOPS focuses on improving four areas: contribution to fleet readiness and the health of Naval Aviation; FRC performance and product integrity of organic and commercial repairs; the speed of decision-making and business process execution; and management of staffing levels and workforce affordability.

Achieving Mission Alignment

Our playbook for organizational redesign was based on a “Design Thinking” methodology employed by U.S. Special Operations Command and championed by the Naval War College. This methodology suppresses preconceived solutions, encourages divergent inputs and challenges assumptions. In addition, we visited numerous companies in the aerospace business and benchmarked world-class performance.

Vignettes reflecting day-to-day operations were used to highlight the impacts of NAVAIR processes on mission accomplishment. A change management and communication strategy was developed and employed throughout the organizational redesign. Feedback from NAVAIR employees indicated concurrence with the need to reduce layers of review and empower employees to decide and act. But many also expressed concern over changing roles and authorities, making the change management and communication strategy critical to successful transformation. In the end, we collectively agreed that a culture change, enabled by a new organizational construct, was required to meet mission objectives.

The legacy competency-aligned organization (CAO) had been in place for 26 years and emerged during the Base Realignment and Closure Acts of the 1990s. It was designed to preserve technical expertise during downsizing and consolidation of infrastructure. Over time, however, the rigid focus on narrow technical and business disciplines became a barrier to accomplishing our mission.

The new mission-aligned organization transforms NAVAIR into a service organization, providing technical and business support to program offices, FRCs, and the fleet, enabling faster capability delivery and more sustainable readiness. Our objective was to focus all possible resources and talent on these mission areas, while preserving NAVAIR’s responsibilities as the technical authority for Naval Aviation. In doing this, we eliminated numerous headquarters positions (a 28 percent reduction).

process is extensive and demands that maintenance experts and managers have the best tools and

are empowered to make important, time-sensitive decisions at the lowest levels possible. (U.S. Navy)

The new organization is command-centric, ensuring subordinate commands have the requisite resources, empowered individuals and decision-making authorities needed to achieve program and fleet outcomes. The NAVAIR direct-reporting commands (Naval Air Warfare Center Aircraft Division, Naval Air Warfare Center Weapons Division and Commander, Fleet Readiness Centers) are accountable for aggressive plans associated with product delivery, quality, cost, and staffing. Similarly, new NAVAIR headquarters group directors are responsible and accountable for resource allocation, policy development, and the design of workforce enabling tools. The procurement and comptroller groups are additionally accountable for contract and financial execution in support of program offices.

Empowerment and Delegation

Under the CAO, decision-making authority was held by the headquarters competency leads. This resulted in expertise in certain disciplines but led to a bureaucratic decision process and inflexibility when conditions changed or different skillsets were needed. The competencies became subunits, requiring dedicated support staffs and institutional resources to operate. Holding decision authority at the headquarters level was a barrier to execution and speed.

Central to mission-alignment, the new CONOPS establishes technical decision authority for personnel assigned to programs and FRCs, and it enables faster program and project execution. Purposefully decentralized, technical decision authority is the authority to determine technical solutions based on experience, established standards, and analyses and recommendations provided by subject matter experts.

Those empowered with technical decision authority do not establish the standards but are trusted to make informed decisions based on those standards. Decisions must consider the entire lifecycle of the end item and are expected to be made thoughtfully, with the appropriate amount of rigor, while keeping in mind that agility and responsiveness are paramount to mission effectiveness. Sufficient checks and balances still exist to identify problem areas without unnecessarily delaying mission execution.

Integration of Functions and Adaptability

Another foundational tenet is the integration of functional disciplines to effectively execute NAVAIR’s mission. Under CAO, the competencies performed specialized functions with a high degree of technical expertise, but without full connection to the larger mission. For example, cost experts were not routinely involved in proposal analysis, despite having analytical skills and data that could significantly reduce procurement cycle times.

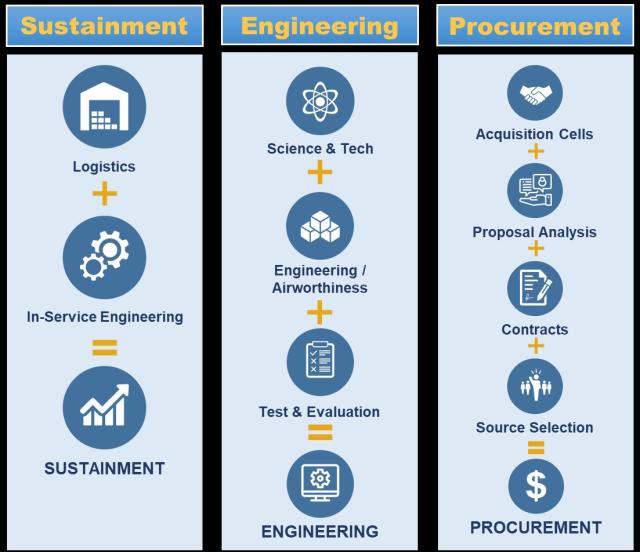

NAVAIR’s new Procurement Group takes advantage of all command expertise to streamline contract actions and source selections. Likewise, the new Sustainment Group sets policy and provides tools and services for FRCs and program offices, focusing on both engineering and logistics. Test and evaluation, long its own entity, is now integrated under the new Engineering and Cyber Warfare Group from a policy, process, and tools standpoint, greatly reducing administrative redundancy. The test wings and test squadron commanding officers have assumed full authority and accountability for execution of flight test.

Greater integration allows us to increase speed and adaptability and reduce costs. As the environment changes, NAVAIR is now positioned to shift resources to stay relevant and ready for new and expanded mission responsibilities. This integrated concept is shown in Figure 1.

Interrelationship with Naval Sustainment System (NSS) Reforms

During NAVAIR’s realignment, the NAE embarked on a series of reforms to improve fleet aircraft readiness by using best practices from commercial aviation. The pillars of NSS include: FRC reform (heavy depot, component repair, and in-service repair turnaround time reduction); supply reform; organizational-level maintenance reform; acceleration of engineering support services; and establishing a maintenance operations center (MOC) to control maintenance, supply distribution, and aircraft inventory management. In addition, NAVAIR and the program executive officers established a reliability control board for each platform, similar to boards employed by commercial aviation. An executive board, which includes full participation by NAE leadership, directs project resourcing and resolution of enterprise-wide systemic degraders, such as supply chain forecasting, corrosion, wiring, and data acquisition. At the heart of these reforms is response and optimization through engineering rigor and data analytics. Years of refining these fields are now being applied to achieve fleet outcomes.

NSS reforms were naturally integrated into the mission-aligned organization CONOPS since both concepts involve aligning resources to mission outcomes. Just as NSS aligns all supporting organizations to accomplishment of readiness outcomes, NAVAIR’s mission-aligned organization ensures that all components of the command are positioned to successfully achieve readiness and other fleet outcomes, supporting the program executive officers, program managers and FRC commanding officers in NSS transformation and sustainment. This is especially critical as NSS reforms expand to capture cost savings from support infrastructure efficiencies for reinvestment back into naval aviation, as prioritized by the Air Boss and DCA.

Results to Date

While additional work is required, initial results are promising and demonstrate the merits of mission alignment.

- Readiness: Naval Aviation readiness has improved by 13 percent overall, with mission-capable (MC) rates increasing from 55 to 68 percent. Results for Navy-specific platforms show an increase from 56 percent MC at the beginning of FY19 to 70 percent at the end of FY20.

- FRC performance: In FY20, the FRCs met or exceeded performance requirements for total components, critical components, and aircraft deliveries and exceeded the financial plan by $66 million. After five years of operating losses, this strong performance helped the Navy weather the impacts of COVID-19, and, most important, ensured fleet units on deployment and preparing for deployment were fully equipped.

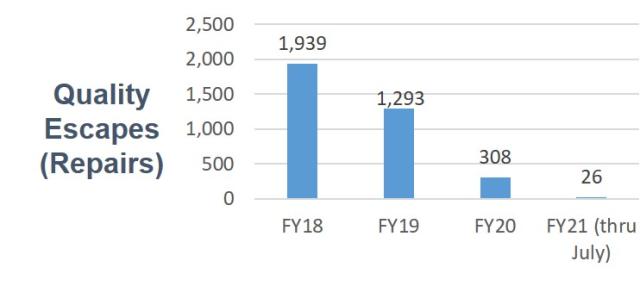

- Quality: Quality escapes are material defects in parts/equipment that are delivered to the fleet, disrupting readiness. Although not eliminated, the number of deficiencies (from the FRCs, inter-service depots, and industry) are down from nearly 2,000 escapes in FY18 to 308 in FY20 and are trending well for FY21. Progress is shown in Figure 2.

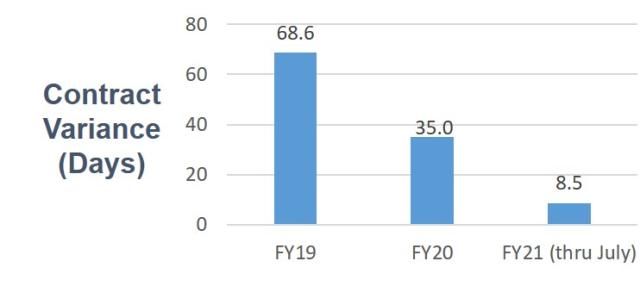

- Speed of procurement and financial transactions: Numerous acquisition approvals have been delegated to PEOs and lower echelon commands. As a result, procurement performance improved by approximately 50 percent in terms of meeting program and fleet need dates, with average variances improving from 69 days in FY19 to 35 days in FY20, as shown in Figure 3. Competitively awarded contracts generally met or beat required timelines. Through empowerment and elimination of duplication, financial transaction processing has improved from 12.2 days in FY19 to 9.3 days in FY21, saving more than 40,000 days of processing time annually.

Industry Alignment: The Next Opportunity

Fleet success depends on efficient, high-quality, and cost-effective maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) of aircraft and components. While we have made great strides in readiness by improving turnaround time, lack of data remains a persistent barrier to next-level maintenance performance—performance levels typical of commercial airlines and MRO companies. We lack data in two important areas: teardown and repair data for components repaired under commercial contracts; and detailed structural data required for establishment of organic aircraft and component repair capabilities.

In the first area, this data is required to optimize maintenance planning, improve supply chain forecasts, and identify opportunities for reliability enhancements. In our visits to numerous commercial aviation companies, we found repair data provides the foundation for reliability control boards and safety management systems.

In the second area, data is required to establish intermediate- and depot-level maintenance capabilities. I-level maintenance is common for naval aircraft because of shipboard operations, where access to global supply networks and transportation can be limited. Depot-level maintenance takes advantage of existing facilities and skilled artisans at our FRC’s, spreading overhead costs across multiple platforms and component lines, and ensuring repair capabilities are available long after aircraft are out of production.

Commercial MRO companies have heavy depot repair instructions readily available. In contrast, Navy and Marine Corps programs have had limited success acquiring repair data and obtaining delivery of structural data required for I-level and depot-level maintenance. In recent years, “no bids” for this type of data have become more common, resulting in reliance on prime contractors for repair services.

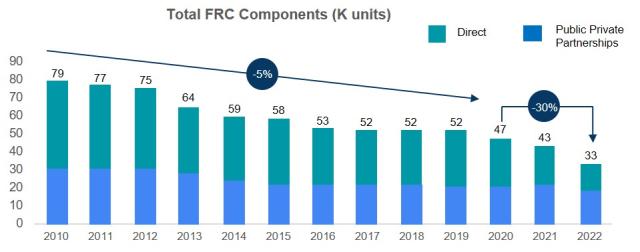

This model differs significantly from Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) regulations for civil aircraft, which require original equipment manufacturers to provide airworthiness maintenance data to owners and maintainers. Manufacturers readily provide this data in support of the FAA certification process, without which their products could not be operated. The magnitude of this issue is reflected in the decline of organic component repairs over the last decade, as shown in Figure 4.

The Navy and Marine Corps rely on the defense industry for the equipment they design and build, and our programs are generally successful in developing and producing formidable capabilities. However, the sustainment side of this acquisition partnership must be redefined. Depot overhaul data, engineering analyses, wire diagrams, and process specifications are required for troubleshooting, maintenance, overhaul, rework, and engineering development of non-standard repairs. Reach-back contracts and special licenses are expensive, time-consuming, and ultimately insufficient in the long-term. We must be able to organically repair our aircraft, engines, mission systems, and components; and accomplish the provisioning and supply chain management of our spares and repairs. Together with industry, NAVAIR can reverse the trends of the past decade and maximize warfighting advantage.

maintenance capabilities on the ship to the author. (U.S. Navy)

Continued Progress

Designing a new NAVAIR with a heightened mission focus—where decisions are informed by data, authority is delegated to the lowest possible level, and functional elements are integrated—has driven substantial and sustainable improvements in mission performance and responsiveness. With an eye on the future, we are proactively transitioning technical personnel to emerging mission areas such as cyberwarfare and network engineering. In FY22, NAVAIR will set even more aggressive targets for speed, readiness, and affordability, but we need industry’s help. Full and proactive access to sustainment data will ensure our warfighters have the best possible equipment and maintenance plans. Naval aviators and maintainers deserve nothing less.

The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Government, Department of Defense, or its components.