What will China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) make of the U.S. Navy’s after-action report on the coronavirus outbreak on board the carrier Theodore Roosevelt? Rest assured the red team will pay the report close scrutiny while digesting the commentary surrounding the affair. PLA thinkers and practitioners do their homework and apply what they learn. Estimating how they will interpret events could furnish a glimpse of how they may modify their practices to compete with the U.S. Navy to greater effect in the near future.

So, let’s look at this prospective foe looking at us.

First of all, the outbreak may reaffirm unflattering impressions of U.S. Navy competence and matériel that have coalesced in recent years. Observers in China could see an antagonist in disarray, plagued by scandal, collisions, engineering woes bedeviling new ships, and on and on. Most recently the amphibious assault ship USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6) burned for four days in San Diego and may be written off as a total loss. The spectacle of a U.S. capital ship being gutted by fire while berthed in its home port will only reaffirm disparaging views among America-watchers in China.

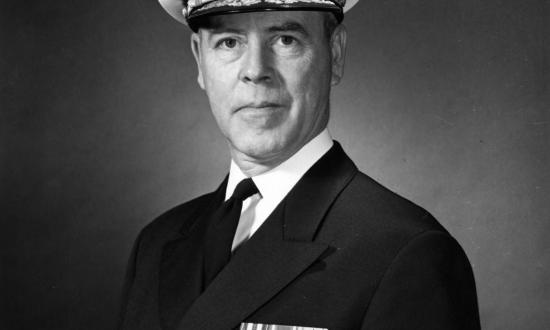

weakness by the Chinese People's Liberation Army. (U.S. Navy photo)

Peril skulks within such impressions. Think about it. If Washington wants to deter Beijing from, say, attacking Taiwan, it needs to make Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders believe in U.S. military capability and U.S. leaders’ willpower to use that capability when and how they say they will. CCP leaders will be deterred if they conclude they cannot defy Washington’s deterrent threats with impunity.

Beijing will refrain from assaulting the island if it knows it cannot win—or cannot win at an acceptable cost. Conversely, Beijing is less likely to be deterred if PLA commanders and their political masters come to doubt that the U.S. Navy and fellow armed forces can defeat the CCP’s aims.

A perverse dynamic takes hold when an open society squares off against a closed one. Strategist Edward Luttwak, in his 1974 book The Political Uses of Sea Power, notes that the differences between political systems can skew impressions of the naval balance. Open societies, including the United States, make a habit of beating themselves up in public over naval and military foibles. Closed societies, like Communist China, go to extravagant lengths to conceal their failings. Otherwise authoritarian rulers fear they will lose face with domestic constituents and foreign interlocutors—and lose power or even their lives in the process. Because the candid contender airs its troubles in public while its rival hides them, the latter appears ascendant at sea—no matter what objective reality might say.

There are upsides and downsides to openness, though. Luttwak maintains that raucous debate about martial matters is actually a good thing. Critique and accountability make an armed force better over time. They are a bad thing in that they may hurt the force’s reputation for prowess in the meantime, and thus degrade its capacity to cow aggressors and hearten allies. That being the case, U.S. Navy leaders must refurbish the service’s image lest allies lose faith in America’s ability to keep its commitments to them, or lest China do something rash on the assumption that U.S. military might has wilted and can no longer stop the PLA. America’s standing in the Western Pacific would suffer either way.

Second, the USS Theodore Roosevelt brouhaha must have reminded PLA officers that U.S. command arrangements in the Pacific are deeply fragmented. The ship’s chain of command sprawled from the ship to Japan to Pearl Harbor all the way to Washington, D.C., when the pandemic struck. Perspectives differed from place to place. Coordinating action against a pandemic proved a chore under trying circumstances; wartime would prove more trying still. The PLA may espy an advantage in this. China’s military aspires to wage “systems-destruction warfare” against the United States and its allies. In other words, if China’s enemies wage war in “systems-of-systems,” (a.k.a. networks), the PLA will try to dismantle those networks. Breaking them apart will spread confusion while simplifying the task of taking down each node in the network once isolated.

PLA commanders may try to pry open the seams in the U.S. Navy chain of command exposed during the Crozier affair—impairing the cohesion of U.S. operations at sea.

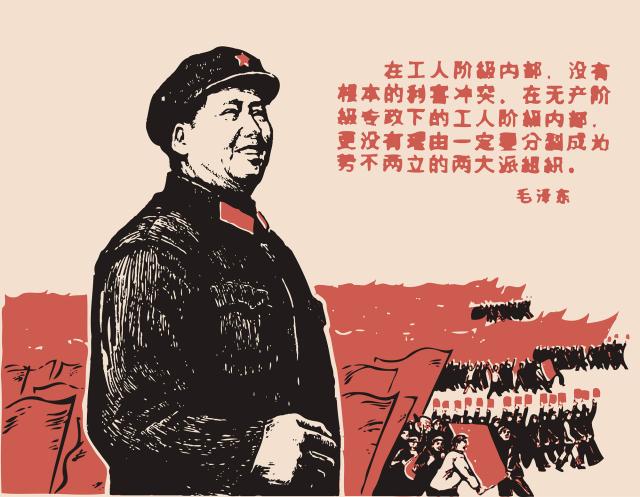

Third, U.S.-watchers in China may take note of the outlook expressed by Captain Crozier in the memorandum that precipitated his firing. “Sailors do not need to die,” Crozier told his superiors, because “we are not at war.” That China’s chief antagonist sees itself on a peacetime footing—and appears overly concerned about military lives—likewise telegraphs opportunity for China. Founding CCP chairman Mao Zedong, who imprinted his way of war on the country, denied that a state of peace ever exists for Beijing. “Politics is war without bloodshed,” proclaimed Mao in a twist on Carl von Clausewitz’s classic definition, “while war is politics with bloodshed.” Maoists are at perpetual war, regardless of whether they are actually spilling blood.

while war is politics with bloodshed," he proclaimed. The U.S. military must accept that its PLA

adversaries see themselves on a war footing already. (Shutterstock)

The PLA may very well conclude it commands a psychological edge over the U.S. military because of its martial mindset vis-à-vis an America in repose. Commanders in China may take an even more aggressive approach during future “gray-zone” operations in such arenas as the South China Sea, Taiwan Strait, and the East China Sea. They will press their psychological advantage trusting that Americans will yield under duress.

Lastly, the role played by information technology in the Theodore Roosevelt controversy cannot have escaped the PLA’s notice. Crozier sent his missive through unclassified email only to see it promptly leaked to the San Francisco Chronicle and published. (The culprit remains unknown.) The ship’s medical staff penned its own letter openly threatening to go public and distributed the letter to scores upon scores of recipients. This bespeaks indiscipline in Navy ranks with regard to operational security. Also noteworthy for Chinese observers is the part played by social media. The report documents how Crozier was taken aback when he started sending the crew ashore in Guam for quarantine and crewmembers took to complaining on social media about living conditions. Social-media posts shaped—and according to the Navy report misshaped—the skipper’s handling of the crisis from then on.

Here, too, China may see an opportunity. The PLA wages “three warfares” on a 24/7/365 basis in an effort to bend foreign opinion in China’s favor. Two of the three are media and psychological warfare. PLA influencers may surreptitiously attempt to use social media to reach into ship’s crews and squadrons, making trouble for U.S. Navy commands from within.

The COVID-19 outbreak on board the Theodore Roosevelt and the fire that gutted the Bonhomme Richard did not telegraph U.S. Navy strength to our Chinese adversaries. Now is the time to exercise some foresight—and shore up our frailties.