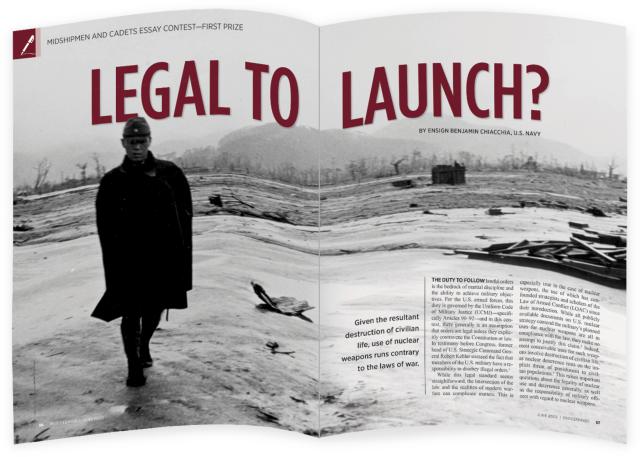

Legal to Launch?

(See B. Chiacchia, pp. 56–59, June 2020)

The abolition of nuclear weapons has long been endorsed by retired flag and general officers. In 1948, General of the Army Omar Bradley opposed their use as contrary to Christian ethics. Retired Rear Admiral Gene La Rocque in 1993 called for the United States to rid itself of nuclear weapons. And in 1996, a group of international flag and general officers signed a public declaration opposing the weapons’ existence. Signers included retired Navy Vice Admiral John J. Shanahan, among others. Admirals Shanahan and La Rocque joined Admiral Stansfield Turner in 2000 to sign a document prepared by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops opposing the existence and use of nuclear weapons.

In 1964 Senator (and Air Force Reserve Major General) Barry Goldwater, candidate for President of the United States, made remarks interpreted as advocating the use of low-yield nuclear weapons to defoliate the jungle in Vietnam. The proposal, however obliquely made, was met with horror and opposition by voters.

Yet the nukes remain. Ensign Chiacchia is part of the latest generation to question their existence and use, militarily, politically, ethically. Before its position in the world as a moral leader erodes even further, and invoking “American exceptionalism,” the nation can show the world that we are no longer hostages to an expensive, outdated weapon program that is ineffective and wrong on many levels and rid ourselves of the figurative nuclear albatross around our necks.

—CDR Earl J. Higgins, USN (Ret.)

I had just finished reading Chris Wallace’s Countdown 1945 (Avid Reader Press, 2020), which details the operational, technical, ethical, and moral issues associated with the use of atomic weapons against Japan, when I read Ensign Chiacchia’s prize-winning essay. It appears that little has changed since 1945, save for the attempted codification of when, how, and if nuclear weapons should be used. It is a tough nut to crack, and the more we learn or diversify the weapons, the tougher it becomes.

A constantly changing global environment adds complexity, putting pressure on the people at the pointy end of the stick, regardless of books of law and rules of engagement.

King Solomon exhorts his son to be equipped with knowledge and understanding and to seek out the wisdom to use it wisely. That wisdom will not be found in law, physics, or military acumen, but must be present at the moment of need. We must ensure our leaders are equipped with it.

—CAPT Art Wagner, USCG (Ret.)

Visual Comms is Worth Another Look

(See P. Pagano, pp. 16–17, June 2020)

While digesting Captain Pagano’s article, I wondered how this could be applied outside of ship-to-ship communication among surface forces. His statements about how visual communications are not limited to line-of-sight is right on the mark. Using manned or unmanned aircraft would be very effective.

By loading a message into a signal system on a plane and sending it to the approximate location that a task group/action group is operating in, commanders onshore can provide information updates, guidance, and/or orders to task group commanders. Furthermore, the task group can send information the other way—conceptually, a modern carrier pigeon.

In combat, with interfaces added to allow data transmission as well as message traffic, elements of a task force could potentially share targeting data without putting the shooters at risk. A perfect example of this would be using maritime patrol aircraft as spotters, identifying targets, and passing target tracks along to shooters who do not use active search techniques to maintain themselves out of adversary’s eyes. Only the aircraft would be at risk of being detected within the EM spectrum.

Elements within the different Navy communities and the larger joint force should begin looking at how they can support being part of a visual-only communications network and what they need to do to support. We need to begin testing this at sea, soon.

—LT Avery Sheridan, USN

The Proceedings Podcast

(Air date: 2 July 2020)

The Burden of a Black Naval Officer

(See D. Walker, online, June 2020)

Recently an old colleague of mine, Lieutenant Commander Desmond Walker, was interviewed on the Proceedings Podcast regarding his article, “The Burden of a Black Naval Officer.” The hosts, both of whom are white males and retired naval officers, noted that they and many of their white male officer peers were hesitant or even scared to discuss and/or confront their black/minority or female subordinate officers regarding their performance if they deemed it was below performance expectations. Both admitted on air that what drove their fear was the belief that the subordinates would file an Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) complaint or grievance.

The thing that I find striking about these revelations is that they (the moderators) truly believed there is something devious in the nature of these black/minority/female officers that would cause them to resort to slander and destroy the careers of superior officers who were just doing their job. Unfortunately, this irrational belief is rooted in a long and vile form of racism and sexism that naturally assigns devious intent—such as conning, scheming, and manipulation—to black Americans and minorities, as well as the stereotype assigned to women officers as “cold-hearted females.”

This wicked taint is the exact reason why police in the United States disproportionately harass and kill black folks—the killing of George Floyd being just one recent example. It is exactly the reason why black folks and other minorities are followed and spied on in stores and malls. It is also a significant reason why black and minority officers have a problem advancing to the general and flag officer ranks in the Navy and other services.

It is stunning to note that the hosts did not seem to have this same concern when dealing with white male subordinates whose performance was substandard, even though white males can file EEO complaints just like their black peers. The hosts never noted where this fear of an EEO complaint came from, nor did they claim to know of or provide supporting evidence of white officers wrongly accused of racism or sexism resulting in these officers’ careers being destroyed. From this writer’s perspective and research, whenever the Navy or other military services has made a determination of racism, discrimination, or sexism against an accused, it is because an investigation found evidence of racism, discrimination, or sexism—in some cases, all of the above.

I believe both hosts are decent, hardworking, and patriotic Americans. Unfortunately, like the rest of us, they are victims of this country’s racist legacy, which has deeply permeated every aspect of society from education, to history, to social interaction, to cultural and political life. Until we, as a society, commit serious economic and psychological resources to overcoming these deeply held beliefs and perceptions, the nature of black people will always be perceived as “devious”!

—CAPT Jerome D. Davis, USN (Ret.)

Editor’s Note: I shared my story on the podcast because I realized how wrong I was at the time to fear such a reaction and because I realize now that such fear is part of the institutional racism that Commander Canady and Lieutenant Commander Walker were talking about—and, hopefully, to allay such fears among white leaders in the Navy today. Thank you for picking up on it and writing about it. I could not agree with you more.

—CAPT Bill Hamblet, USN (Ret.),

Editor-in-Chief, Proceedings,

and Podcast cohost

On this Juneteenth 2020, amid recent unrest across the nation and the world, I feel inspired to write about my experience and perspective as a black officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve.

America is on fire. On top of the economic shambles caused by the pandemic, there is blatant social injustice toward African Americans at the hands of law enforcement that we can no longer ignore. The people we should trust to serve and protect us have caused the deaths of Breona Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and—most viciously—George Floyd, unarmed and in police custody. Mr. Floyd’s inhumane death has incited a movement that has spread across America and around the world.

Unfortunately, after many years of progress towards racial inclusion, even after the country elected its first African-American president, the facts speak for themselves. In 2020, there are still racists living in our midst.

But we should not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Despite the racists among us, all of America is not racist. The vast majority of Americans are decent, fair-minded, and hardworking people, and the United States is still by far the greatest country on earth.

America is not perfect, but it aspires to be the light that shines in the darkness, with equal justice under the law for all of its citizens. I believe in our shared humanity. I believe that you have everything you need to be a great success. You can do anything you set your mind to in this country.

Only in America can a black kid from Hawaii with a funny name grow up to one day become the (historic) first African American president. Only in America can a young Austrian with just $20 to his name become the highest-grossing actor in the world and the “Governator” of California. Only in America can a poor black girl from Mississippi become the most beloved and popular talk show host in TV history and the wealthiest woman on the planet.

And only in America can a preacher from Atlanta help lead a civil rights movement that would provide civil rights for an entire segment of the American population, bringing the country closer to its original ideal: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

America is an exceptional place. My godfather used to say, “12 million illegal immigrants cannot be wrong.” America must be very special for millions of people to risk their lives to come to our shores.

Despite much progress toward equal justice, we still have a lot of work to do. We need a majority of Americans to speak up and fight social injustice anywhere and everywhere it might be found. We cannot remain silent anymore. We cannot stay indifferent in our privileged bubbles. There is a significant portion of our population that is hurting right now; we need all hands on deck to do whatever each of us can, even in small ways, to right a wrong, and contribute toward a more perfect union.

For us as sailors, the best way to do that is to live out our core values of Honor, Courage, and Commitment and to reaffirm our solemn oath to support and to defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic.

—LCDR Bob F. Zinga, USN

Flag Officers of the Naval Services

(See pp. 103–16 and 119–24, May 2020)

In these times of heightened racial tensions in the United States, I have started noticing things I had not noticed before. In 20 years in the Navy, I believed my service gave every member an equal chance. But looking through the photographs in the flag list I was startled by the lack of diversity at the flag level in the Navy and in the Joint Chiefs of Staff. I found zero people of color at the admiral level, and only one among the rear admirals. The Marine Corps was better, but not by much. We can—we must—do better, not just for minority service members, but for the health of our services and the health of our nation.

—LCDR Monica Arnold, USN (Ret.)

Naming the Future Doris Miller (CVN-81)

(See R. Alley, p. 8, March 2020; L. Moyer,

p. 88, April 2020; T. Phillips, pp. 147–48, May 2020; and E. Coop, p. 9, July 2020)

There are more than enough sailors and Marines who have been awarded decorations for valor to solve the ship naming problem once and for all. Many ships have been and continue to be named for individuals who have no connection to or place in naval history, a distasteful practice that has gone unchallenged for too long.

Like many problems, however, the solution is simple. Any ship named for a person will be for a sailor or Marine who has been awarded the Silver Star or higher (and if we run out of those, we’ve got a great problem on our hands, as we’ve certainly surpassed the 350 ship mark!)

Ships currently in the fleet whose names do not meet that criteria should be immediately added to a list for renaming. Exceptions should not be made. This means renaming a large portion of our carrier fleet. So be it.

I served on board the USS Rentz (FFG-46), named after the only Navy chaplain in World War II to be awarded the Navy Cross, granted posthumously after the USS Houston (CA-30) was sunk by a Japanese submarine in 1942 in the Sunda Strait. Chaplain Rentz sacrificed his life jacket—and life—for a shipmate. Why do I know this? Because the Navy was wise enough to name my ship after him.

—CDR Brent T. Meyer, USN

Lieutenant Commander Phillips’ critical analysis of aircraft carrier naming brought back my concern about the naming of submarines. Initially, submarines were identified by numbers, letters, or a combination. From about the 1930s to well into the 1970s, attack submarines were named after fish. In the 1960s, the first ballistic-missile submarines were named after famous Americans and presidents. Currently, submarines of both types are named for states, cities, people, and historical events or places.

Only one active sub, the USS Seawolf (SSN-21), retains the name of a fish. And a very important name it is, as it reflects the World War II submarine fleet, the majority of which were named after fish.

The Navy has lost a total of 52 submarines over the years, 48 of which were lost during World War II, most by combat action, including the USS Seawolf (SS-197). We need to continue naming at least one or two new attack submarines with the name of a “fish boat” that never returned. Of the 48 that never returned, there are several fish-named subs whose valiant actions reflect the Navy’s fighting tradition, remind us of World War II history and the many sacrifices made, and honor those that never returned.

I have no objections to the naming of future submarines for cities, states, and deserving Americans, as submarines have graduated from “boats” to capital ships of the line. But wouldn’t it be great if a whole new class were named after the USS Wahoo (SS-238)?

—CAPT Robert J. Decesari, USNR (Ret.)

Incident at Ladd Reef

(See E. Cerne-Iannone and P. Farace,

pp. 68–72, July 2020)

The authors do a good job describing the final days of this ship and the effective work of the USS Cod (SS-224) in rescuing the crew. However, the reader might wonder why a Dutch submarine with a British liaison staff on board was based in Australia when it was transiting the South China Sea.

At the time of its loss, the O-19 was based at Fremantle, Western Australia, as part of the Royal Navy’s Fourth Submarine Flotilla. Three Dutch submarines and several surface ships arrived in Fremantle in March 1942 after the Netherlands East Indies (modern Indonesia) was captured by Japan. Fremantle became a concentration point for Royal Netherlands forces operating in the Indian Ocean. Prior to the arrival of British submarine flotillas in Australia in 1944, the few Dutch submarines at Fremantle operated alongside the U.S. Navy for intelligence operations and combat patrols into the NEI.

One other note. The O-19 was unusual, a purpose-built minelayer, and she also was the first Dutch submarine equipped with a snorkel as a result of interwar experiments. While the snorkel was not used by Dutch boats once they came under British operational control, incomplete units of the O-21 class captured by the Germans led to the Kriegsmarine developing their own version of the snorkel.

—Mark C. Jones

Introduce Wargaming to Wardrooms

(See T. Dixon, pp. 82–83, July 2020)

I am so pleased that professional wargaming is a subject we are hearing about in Proceedings.

I would like to offer Commander Dixon two suggestions. First, you may already have experienced wargamers on your boat. I was an enlisted submarine sailor on the USS Hammerhead (SSN-663), and I know from experience that we had historical wargamers on board who would have been able to assist. Such gamers could even run the neutrals and merchants that often need to be considered in a naval wargame.

Second, wargames can be treated as a simple problem played between two officers over coffee in the wardroom. Examples could include covering multiple choke points with limited assets or assessing how the red player could obtain local superiority for a limited time frame.

—Jonathan Yuengling

An Expeditionary Support Ship for a Navy-Marine Team

(See W. Stearman, online, June 2020)

Mr. Stearman’s proposal to convert very large crude carriers (VLCCs) to expeditionary ships (ESs) to project power and effect forcible entry is not viable.

As the author notes, “Technological progress by future adversaries has made amphibious assaults too hazardous,” and “Navy amphibious ships are safe only when at least 100 miles from a contested or hostile shore.” In the era of carrier-killer ballistic missiles there is no reason to believe that VLCCs would be any less vulnerable, no matter how heavily armored, than a carrier or large-deck amphib.

Even if the idea were sound, it is impractical, as the Chinese could rapidly build more of such ships than we ever could, given our deficiencies in domestic shipyard capacity. The United States is not among even the top three shipbuilders in the world.

Costs involved in conversion invariably are higher than for similar, custom-built ships. And the electric motors the author suggests would require tremendous power plants; gas-turbine power plants are not a viable or economical solution. There is a reason the Navy has used nuclear power for more than 50 years to power aircraft carriers.

—LCDR Scott A. Wallace, MC, USN

Submariners are Warriors First

(See K. Chiang, pp. 67–68, June 2020)

Congratulations to Ensign Chiang for his Capstone essay. But officers should be reminded that things may not always be as they appear. Within the story of the “failed” hunt for the Russian submarine Severodvinsk there are many possibilities.

Think about your counterparts in the Russian Navy. Would they be interested in getting a better idea of the capabilities of the U.S. Navy in the event that a very quiet Russian sub made its way into the Atlantic? Of course they would! You may depend on Russian counterintelligence knowing where to drop a hint that the Severodvinsk was going on patrol in the Atlantic. The sub would be observed by U.S. satellites leaving port and submerging. But instead of proceeding to the Atlantic, she would remain quiet and within Russian territorial waters for the duration of her patrol. In the meantime, the Russian Navy could then carefully observe the U.S. response. Unless the Severodvinsk surfaced 30 miles off Norfolk or made a port call in Havana, was it ever really there?

Now consider the possibility that the Severodvinsk actually did enter the Atlantic and that the U.S. Navy has the ability to track her. Is this something you would want the Russian Navy to know? What better way to convince them that the U.S. Navy is unable to find the sub than by staging a massive and futile pantomime. The U.S. forces involved in the “search” would be intentionally dispatched to places where they knew the Severodvinsk was not to establish the authenticity of the effort. This would leave the Russians with the problem of having to decide whether they had a wonder weapon, the Severodvinsk was just lucky, or the U.S. response was a deception operation.

The takeaway is that officers need to expand the width and breadth of their thinking. Victory in battle is determined not so much by the capabilities of the weapons involved, but by the imagination and courage of the women and men who deploy them.

—Guy Wroble

Warfighting Demands Better Decisions

(See G. Galdorisi, pp. 32–35, June 2020)

Captain Galdorisi mischaracterizes the relationship between humans and

artificial intelligence (AI). As a result, he incorrectly concludes that humans are in danger of becoming subservient to algorithms and argues that humans should always control AI systems. However, humans have not been “dumbed down” by AI, nor are they at risk of becoming subservient to it for the foreseeable future.

Instead, AI serves to improve human efficiency by freeing us from mundane tasks. Furthermore, autonomy is not a black-and-white issue. There isn’t even a generally accepted definition of machine autonomy. But all AI systems lie on an autonomy spectrum, based on their capabilities and what autonomous actions humans assign them. Indeed, the relevant debate is not if humans should control AI, but rather the extent to which AI systems should be allowed to operate autonomously.

None of the examples provided in the article are instances of humans serving as slaves to AI overlords. In fact, they highlight how AI can free humans from wasting time on narrow, mundane, and easily repeatable tasks and allow us to focus on the higher-level cognitive tasks for which AI is ill-suited. With this framework in mind, it becomes clear that the “intelligent assistant” in the Ford Fusion allows its driver to spend less mental bandwidth on fuel economy, and more time thinking about higher-level priorities such as safety. The human driver—not the “intelligent assistant”—is very much in control.

As in any other domain, tasks that are easily repeatable should be considered for automation. Yes, humans should exert control over autonomous weapons. But the real question is not if humans should control AI systems, but how.

For military AI systems, it is vital to consider the context in which they operate, the rules of engagement, and the benefits and risks of automating various tasks. For example, in peacetime it is likely not worth the risk of allowing a drone system to engage targets autonomously.

During a large-scale war that uses numerous autonomous systems, however, the benefits of allowing a drone to automatically engage other drone targets (which it can do much faster than any human) may outweigh the risks.

Even in this scenario, humans are still in control. A human should decide to allow the drone to enter or exit a fully autonomous mode. The human can also give restrictions for the drone, such as limiting the drone against engaging specific targets or imposing geographic boundaries on autonomous operations. With these restrictions, the AI system is relegated to performing routine tasks, while the human remains in control and can focus on higher-level priorities.

—Keith Wilson

Let Sailors Be Tactical Incubators

(See R. Hilger, pp. 26–31, June 2020)

A partial solution to the fleet size problem can be seen in the 2019 San Diego-to-Pearl Harbor-to-San Diego voyage by an unmanned Navy ship, the Sea Hunter. Such a ship could be the harbinger of how to increase Navy force levels at a more reasonable cost than traditional manned warships. Although an unmanned ship cannot undertake all assignments given to a manned one, there are important roles that an unmanned ship could fulfill. And when more than one-half of the total ownership cost of a ship is directly related to people, reducing manpower-related costs is compelling.

Identifying the optimal use of unmanned surface ships will require a novel blending of people and technologies to enable cost-efficient and cost-effective concepts of operation. While the Navy, Department of Defense, and outside experts work on various fleet compositions, all versions rely heavily on connectivity and interoperability.

As Lieutenant Commander Hilger explained: “Unmanned systems have changed war on and over land. Intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, targeting, attack, and logistics all have benefited from unmanned systems use.”

In May 2020, Naval News reported that the Commander, U.S. Fleet Forces Command, Admiral Christopher W. Grady, had directed the Navy’s surface forces to develop a concept of operations (ConOps) for the large and medium unmanned surface ships now under development. The ConOps will address interoperability challenges to basing, sustainment, and deployment concepts. With respect to missions, the ConOps for “medium” unmanned ships will focus on intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and electronic warfare, while the “large” ship ConOps will address surface warfare and strike operations.

Admiral Grady says the ConOps, expected in late summer, could affect operations with individual ships, as well as aircraft carrier and expeditionary strike groups and surface action groups.

While having an unmanned ship will cost far less than a conventional naval ship, the unmanned platform would still have minimal accommodations for boarding parties, technicians, and possibly other “temporary occupants.” These would be flown aboard by helicopter if and when required for specific operations.

—Norman Polmar

The Minesweepers of Wonsan

(See A. Clift, p. 75, June 2020)

Mr. Clift’s illuminating article about Rear Admiral Sheldon Kinney’s career highlights the often overlooked subject of mine warfare, especially in Korea. However, the first paragraph (describing Kinney’s World War II record) caught my attention, because I had never heard the claim that the USS Bronstein (DE-189) sank three U-boats and damaged another “in a single night’s convoy protection action.”

Apparently, the claim must have arisen from wartime assertions, because there appears to be no supporting evidence elsewhere. I reviewed a number of online sources, including uboat.net, one of the finest naval websites afloat, as well as Admiral Kinney’s Navy Cross citation.

In 17 days of March 1944, the Bronstein attacked “a non-sub target,” damaged the U-441, and collaborated with TBF Avenger torpedo bombers from the USS Block Island (CVE-21) and the Corry (DD-463) in sinking the U-801.

A triple-kill submarine action surely would have generated more notoriety than the literature seems to contain. However, if additional documentation is available, it certainly would be welcomed by Proceedings readers.

—Barrett Tillman

Get Your Own Jacket

(See M. Frattasio, p. 15, April 2020

and A. King, p. 146, May 2020)

Despite four years at sea as an officer-of-the-deck (and more) in both amphibs and destroyers, I carefully describe myself as a “surface warfare officer” with small caps.

I was not a career officer, but those “surface warrior” years—including two formal letters of commendation from CincLantFleet and my own admiral for service in the Cuban Missile Crisis on my 25th birthday—taught unforgettable lessons of teamwork, leadership, responsibility, and much more. With some of my own profession’s highest decorations and honored six times by four governments (including my own, for three decades of pro bono support of “the foreign policy and national security interests of the United States”), I often describe myself as a “former naval officer.”

As for the flight jacket, I recall photos of a Chief of Naval Operations swanning about the Pentagon in his leather jacket with naval aviator’s pin and thinking “how insecure.”

—Terence R. Murphy, Life Member