Imagine you are responsible for a swath of land in a protracted counterinsurgency operation. You decide to consider some metrics and find cause for optimism. Among more than 12,000 friendly sites, on average, fewer than 25 come under insurgent attack each day (99.8 percent protection rate); fewer than 800,000 of the area’s 6 million people live in contested areas (approximately 13.3 percent); about 90 percent of all population centers have elected governments; agricultural production has risen nearly 25 percent; and you can drive unescorted to any provincial center during daylight hours.1 By these and other basic data-driven metrics, objective analysis shows that your area of responsibility is increasingly successful.

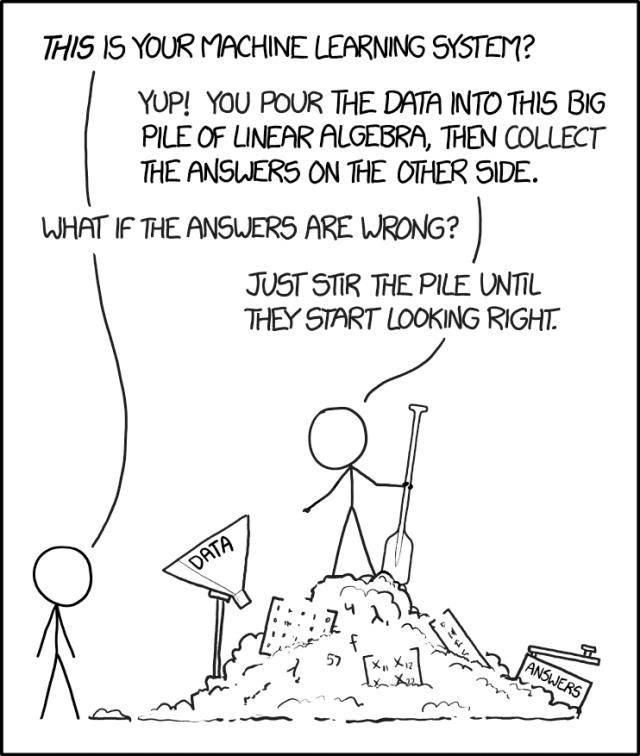

Now conceive of exponentially more data points and a more complex system of analysis. Instead of these few variables you have been tracking, you can track thousands of variables simultaneously. Where you may have failed to observe that those daily attacks disproportionately tend to occur a few days after heavy rainfall, the automated algorithms that continuously pore over your data noted it as one fact among many others. Armed with dispassionate and automated data analysis, you are empowered to make more-informed decisions, if the data collection and management do not first overwhelm your capabilities.

The U.S. military is not entering the age of big data analytics and machine learning; it is firmly inside it, riding the “peak of inflated expectations.”2 The spell of this digital sea change should be especially mesmerizing to the Marine Corps. Predictive analytics promise to illuminate the future, enabling warfighters to “exploit tempo and the continuous flow of events to suit [their] purposes,” resulting in faster, better decisions.3 The promise of this data revolution will be to manage (in the words of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld) the “known unknowns,” and perhaps more important, reveal some “unknown unknowns.”

Analytical rigor usually is viewed as objective—robust in the face of distortions such as personal biases and conflicting priorities. Furthermore, it limits at least partially the need to apply individual judgment to a decision, which is particularly attractive to an organization with standardization woven into its core. And it can be indiscriminately applied. The neoconventional wisdom is that if you do not understand a problem, you collect data on it until you think you do. Even if you do understand a problem, you collect data until you understand it more thoroughly or in a different way. To data acolytes, deterministic consequences are hiding everywhere in plain sight, if you only know where to look.

Formulate an AI Strategy

The Marine Corps appears to have bought in. Replete with data buzzwords, the 2018 “Marine Corps Concepts and Programs” envisions a command-and-control (C2) network that “will leverage technologies such as artificial intelligence [AI] and machine learning [ML] to automate data processing and dynamically adapt to the environment,” specifically extending into a logistics C2 structure “enabled by artificial intelligence that is data driven and predictive.”4 Such language closely follows the 2018 National Defense Strategy mandate to “invest broadly in military application of autonomy, artificial intelligence, and machine learning, including rapid application of commercial breakthroughs, to gain competitive military advantages.”5 Unfortunately but predictably, “Concepts and Programs” consigns these tools mostly to information warfare.

As ML and data analysis increase in complexity, they will affect every aspect of Marine Corps operations, not only information warfare. Technological revolutions are just that because their effects reach far beyond their traditional domains of origin. While the “Marine Corps Operating Concept” (MOC) imagines an infantry that “exploits man-machine and artificial intelligence interface to enhance performance,” it does not explicitly define the potential breakthroughs as applying to all the service’s functions.6 Can the Marine Corps visualize the benefits of cutting-edge analytics across its range of operations?

It is possible that references to AI and man-machine teaming are just cases of organizational “AI-washing.”7 In the modern rush always to embrace the latest technology, many civilian businesses have found themselves buying AI without clearly defining what they want it to do. Nearly 85 percent of global business leaders view AI as enabling or sustaining a competitive advantage, while less than 39 percent have an AI strategy.8 They might not know exactly how AI can help them, but they want it, nonetheless. Is the Marine Corps ready to become an early adopter of such technologies, or is it destined to be a laggard?

Knowledge and data are not synonymous, and the warfighter needs the former more than the latter. Increasing the amount of available data without deliberate, well-constructed hypotheses determined in advance will only amplify the noise and obscure the signal. This is not a hypothetical problem with big data. Measuring the wrong things or attempting to derive theory solely from data is a good way to be fooled by mere coincidence. For instance, in our hypothetical counterinsurgency, a correlation between insurgent attacks and the average monthly temperature a continent away might exist, but it is bound to be coincidental, not causal.

As the Marine Corps seeks to leverage the tools of the data revolution, it must wrestle with two fundamental facts: It is inadequately prepared to adopt those tools, and it must resist the temptation to become enslaved by data during adoption. The first is easier to address. Marine Corps leaders can accelerate the pace of technological adoption by using a blended approach consisting of vision, outreach, and incentivization.

Without an overarching data analysis strategy or clear guidance for how to employ ML and other data analysis tools, however, it will be easy for the Marine Corps to give in to temptations—forcing patterns onto randomness, measuring inconsequential variables, and searching only for those things it wants to find. Maintaining awareness of the forest while measuring individual trees may prove difficult.

The Noise Before Defeat

The Art of War notes, “Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.”9 The Marine Corps lacks a unified strategy for how to acquire and embrace the tools of data analytics, but there are isolated pockets of awareness that can and should be used to build momentum across the force. Loosening what the MOC calls “hierarchical constraints on data collection, production, and dissemination” is a component of evolving the Marine air-ground task force, albeit from a C2 perspective. Recent (and encouraging) administrative announcements call for data innovation in logistics as well as reclassification of military occupational specialties to address data science.10 This type of thinking should be expanded.

In the very near future, fluency in data science principles—and the ability to leverage analytics as a tool—no longer will be relegated only to specialists. It will be demanded of leaders across the force, in the same way all Marines are expected to embrace a mind-set of operating in the contested littorals. Those who remain illiterate will fundamentally misunderstand these tools as magic black boxes, grasping neither their power nor their limitations.

To help prevent this, Corps leaders should publish a vision for how the entire force should embrace the data frontier. For example, the next “Concepts and Programs” could recommend attachment of data specialists to all regimental-level units. Such specialists would be tasked with exploring what quick wins can be achieved using basic ML techniques, gaining adherents and exposure in the process. Whatever the experimentation, the hypothesizing needs to begin in earnest and across all warfighting functions.

Real Artificial Progress

The Marine Corps does not need to go it alone. These and related concepts are being worked on across industry and the Department of Defense—even within the Marine Corps. The Defense Innovation Board exists to encourage military adoption of innovative civilian technology. Practical applications of expanded AI, such as the X-47B unmanned combat air vehicle, the MQ-8 Fire Scout, or the Antisubmarine Warfare (ASW) Continuous Trail Unmanned Vessel, show the impressive results of top-down directives to increase automation and embrace AI. As far back as 2015, former Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus directed the Chief of Naval Operations to “coordinate with the Marine Corps to identify opportunities to use AI and robotics in integrated Navy-Marine Corps applications.”11

But AI traditionally has been viewed through the lens of automated machines. This undoubtedly is a very powerful view, but an incomplete one. Rather than embracing an understanding of AI’s fundamental concepts, this view simultaneously encourages complacency and distancing, seeing AI as a vastly complex endeavor that may replace various tactical functions but is beyond the comprehension of mere mortals. A more complete view would recognize that AI can support decision-making with relatively cheap, basic programming techniques—provided the data are available. Leaders such as retired Marine Corps General John Allen are providing insights into how AI might shape the future battlespace. (See “AI Will Change the Balance of Power,” pp. 26–31, August 2018.) Calls for advanced data analytics, mainly from the intelligence function, should continue.12

The present challenge is to expand these calls into all warfighting functions, perhaps by highlighting work being done by teams at the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory and the Department of Operations Research at the Naval Postgraduate School. The ways in which ML might be used to gain and maintain the Marine Corps’ competitive advantage should be more widely shared so the technology can be demystified to spur critique and imagination. All Marines are not expected to be naval architects, but they all must have a grasp of operations on amphibious ships. The Marine Corps should demand the same level of awareness concerning data analytics.

Invest in Knowledge

Society to date has proved unwilling to accept the delegation of decision-making or moral authority to automation. Machines collect data; people make decisions. Given that advanced analytics are tools that aid and guide human agency, it is imperative to train warfighters in the tools’ strengths and limitations. Yet, the Marine Corps does not aspire—nor should it—to become an organization of data analysts. One way to resolve this apparent paradox is to incentivize specific knowledge.

The Foreign Language Proficiency Program (FLPP) addresses a similar need. The FLPP offers financial incentives to those who acquire or possess knowledge of critical foreign languages. Machine-learning techniques, coding expertise, and knowledge of data science principles should be encouraged through similar incentives. This may spur recruitment of highly skilled civilian and uniformed personnel and simultaneously motivate self-starters to acquire new skills. Since these incentive programs need not be exclusive to specific military occupational specialties, they should encourage the diffusion of knowledge across all warfighting functions.

In this way, the Corps will supplement its top-down approach to adopting innovation. Instead, awareness of tools that can be used to address problems specific to particular roles and responsibilities will spread organically. This will empower individual warfighters. The current, top-down model wastes resources finding problems that already are known within the organizational consciousness. Worse, it develops new tools and then goes searching for problems they might solve. It is vastly more efficient to identify and understand the problem then select the most appropriate available tool to solve it. The latter is consistent with the Marine Corps’ culture of adaptability. Empowering Marines to apply—or even develop—such analytical tools will mean they are used in places specialized experts might never have thought to look.

Known Past, New Prologue

This diffusion of knowledge also must include awareness of the limitations of data analytics. Aside from fundamental technical limitations, in a warfighting context, some issues cannot be broken down into constituent variables and modeled by data, no matter how granular. As Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1, “Warfighting,” puts it, “War is fundamentally a dynamic process of human competition requiring both the knowledge of science and the creativity of art but driven ultimately by the power of human will.” Human will is unpredictable and impossible to quantify or measure—and probably always will be. Unless Marines embrace a full understanding of these new analytical tools, they risk entrusting the incalculable to the unknown, conflating the art with the science in the process.

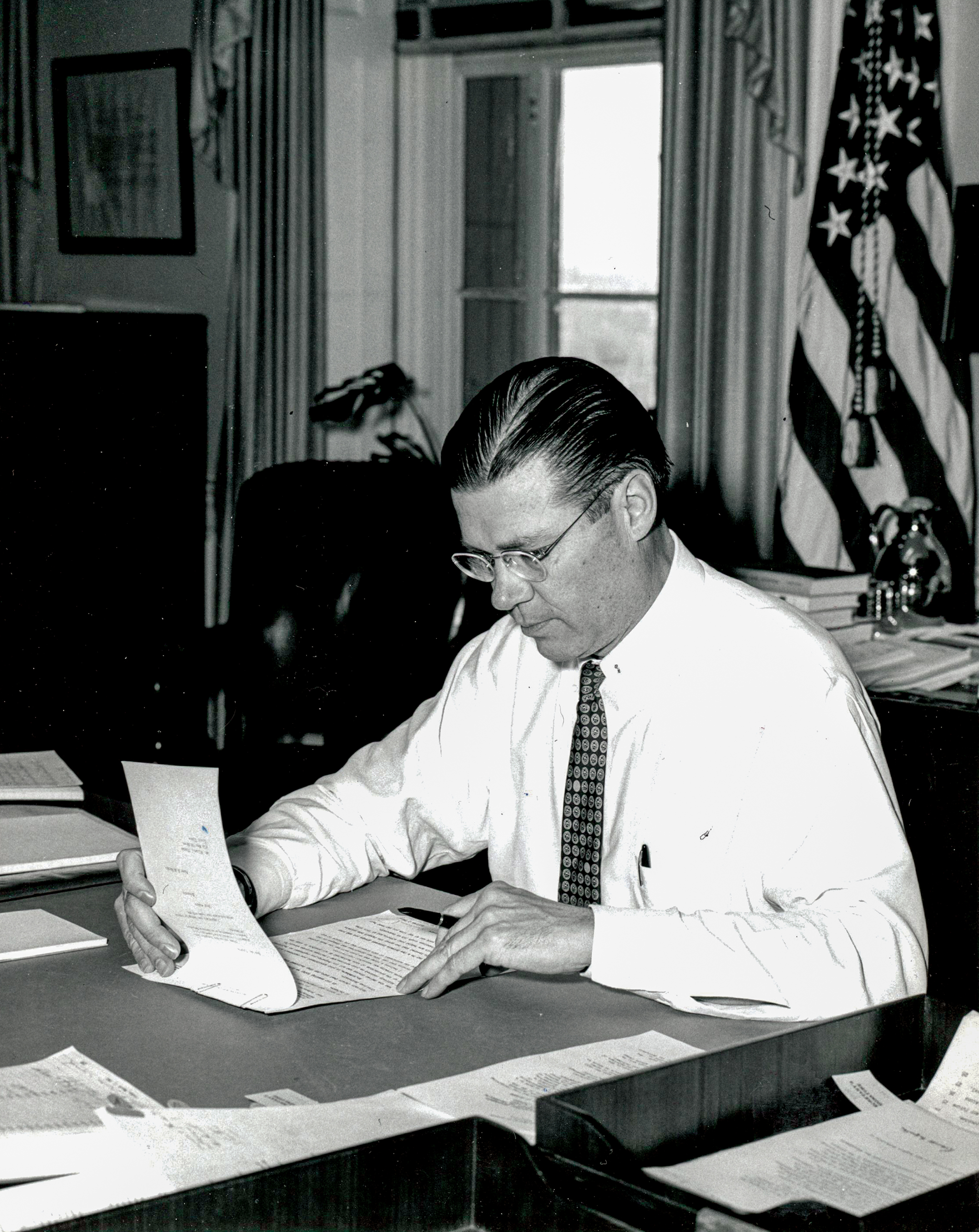

There is precedent for this. Retrospective studies of the Vietnam War broadly criticize then–Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and his insistence on reducing the conflict to a vast series of data points and spreadsheets, especially McNamara’s belief that progress could be accurately measured by the enemy body count.13 The lesson should not be that it was futile to collect data, or that statistical emphasis was the deciding factor in such a complex conflict. There is, after all, some wisdom in his statement, “But things you can count, you ought to count. Loss of life is one.”14

Taken to its extreme, though, this data-emphatic culture can go horribly awry, for example, by rewarding the underestimation of enemy forces to give the appearance of progress.15 Statistics from the early-1970s Mekong Delta, like those of the opening counterinsurgency example, cannot quantify the will of the enemy nor presage an entire conflict’s subsequent events. Neither do apparent tactical successes always translate into strategic victories.

Recognizing the shortcomings of data analytics is not to be defeatist but instead to appreciate its correct application. The era of big data has begun to force paradigm shifts in how decisions can be made and advantages sustained; it is critical for the Marine Corps to embrace both the power and the limitations of these changes. By affirming a vision for implementation across the force, fostering awareness of ongoing research, and incentivizing knowledge acquisition, perhaps the service can avoid chasing the wrong signal and getting lost in the random forests of machine learning—or another Southeast Asia.

The lesson is to know how and when to use these novel analytical tools by understanding them at a foundational level across the Marine Corps. The world produces 2.5 quintillion bytes of data per day—the Marine Corps must figure out how to interact with it.16

1. John Paul Vann, “Opening statement,” Senate Foreign Relations Committee Hearings on Vietnam, 17–20 February 1970.

2. Kasey Panetta, “Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies, 2018,” gartner.com, August 2018.

3. U.S. Marine Corps, MCDP-1, “Warfighting” (1997).

4. U.S. Marine Corps, “Concepts and Programs” (2018).

5. Department of Defense, “Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America” (2018).

6. U.S. Marine Corps, “Marine Corps Operating Concept” (September 2016).

7. “Gartner Says AI Technologies Will Be in Almost Every New Software Product by 2020,” gartner.com, 18 July 2017.

8. Sam Ransbotham, David Kiron, Philipp Gerbert, and Martin Reeves, “Reshaping Business with Artificial Intelligence: Closing the Gap between Ambition and Action,” MIT Sloan Management Review 59, no. 1 (Fall 2017).

9. Attributed to Sun Tzu.

10. U.S. Marine Corps, “2018 Logistics Innovation Challenge,” MarAdmin 443/18 (14 August 2018); “26XX Occupational Field Professionalization,” MarAdmin 495/17 (6 September 2017).

11. Ray Mabus, “Artificial Intelligence and Robotics for Support Functions,” USNI News. (5 June 2015).

12. C. A. Schaffer, “Who’s Your Data? Why Data Needs to Be the New Weapons System of Choice,” Marine Corps Gazette 100, no 10. (October 2016); C. B. Brida, “Small Corps, Big Data: The USMC Need for Open Source Intelligence and Data Analytics,” Marine Corps Gazette 99, no. 8 (August 2015); M. Hastings, “Automated Analytics: Natural Language Processing in Social Media Intelligence,” Marine Corps Gazette 101, no. 9 (September 2017).

13. Kenneth Cukier and Viktor Mayer-Schönberger, “The Dictatorship of Data,” MIT Technology Review (31 May 2013).

14. “Robert McNamara: Obituary,” The Economist (9 July 2009).

15. Central Intelligence Agency Library, “Episode 3, 1967–1968: CIA, the Order-of-Battle Controversy, and the Tet Offensive” (19 March 2007).

16. Ralph Jacobson, “2.5 Quintillion Bytes of Data Created Every Day. How Does CPG & Retail Manage It?” IBM Consumer Products Industry Blog (24 April 2013).