The U.S. Navy has been in steady decline qualitatively, quantitatively, and culturally in its ability to wage naval warfare against a peer adversary since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Navy has lost the corporate knowledge and cultural ethos to fight a peer navy and to prosecute an offensive naval campaign successfully. The causes are many, but of particular note are geopolitical shifts, budgetary pressures, and training focus. The Navy must move swiftly and seriously to escape its predicament while adversaries challenge the United States around the globe and several build blue-water navies and land-based anti-access systems specifically designed to defeat the U.S. Navy.

How We Got Here

Vladimir Putin has called the collapse of the Soviet Union the greatest geopolitical disaster of the 20th century. There may be some truth in that assessment, at least from the perspective that the collapse of the Soviet Union removed the lid from the simmering cauldron of ethnic, religious, and nationalistic conflicts across the globe. For the U.S. Navy, the end of the Soviet Union may not have been a tragedy, but it did result in a loss of identity, purpose, and political support for the service. Politicians, seeking a peace dividend, questioned the need for a large blue-water navy. Senior naval leaders failed to make the case to the nation or political leaders of the enduring need for a globe-spanning fleet trained and equipped to ensure maritime supremacy and safeguard the global maritime commons. To be sure, the Navy was a victim of its own success to an extent. But as the United States and NATO allies cashed in their “peace dividends” and slashed the sizes of their navies, former and rising adversaries started to arm themselves with the tools to challenge the international order—and the diminished navies that nevertheless safeguard it.

Hand in hand with the desire for a peace dividend came the expense of new entitlements and other non-defense spending in the federal budget, accelerating the decline in the funding to man, train, and equip the Navy. The Budget Control Act of 2011—“sequestration”—further exacerbated this fiscal pressure. Senior uniformed and civilian Navy leaders, always eager to appear willing to do more with less, have put this underfunded, under-equipped Navy in the position of maintaining a Cold War deployment tempo of about 100 ships overseas, but with a Navy of fewer than 300 ships, compared to a 1987 peak of 594. The result is a fleet that does not have enough time for adequate maintenance or training.

What training that the Navy does conduct in the limited time between deployments and maintenance periods is both superficial and misses the mark with regard to naval warfighting. Although leaders acknowledge that the Navy has to be prepared to fight a peer adversary at sea, training emphasizes defense over offense, control of escalation, and a law enforcement mentality versus a warfighting one on the part of tactical decision makers and watch standers. Strike groups do not train to take advantage of speed, maneuver, and offense, but instead are admonished “not to cede battlespace,” as if they are ground units holding a hill. When ships operate from fixed locales, such as carrier operating areas, they surrender all the advantages inherent in naval forces and instead fight battles of attrition that give all the advantages to the adversary. Fighting from a sea bastion is a viable tactic under certain conditions, such as when the geography supports it, but applied broadly sets up tactical decision makers for defeat.

This defensive, ground combat–influenced focus has come about from recent experiences. Since 11 September 2001, the United States has been engaged in ground wars primarily against asymmetric, nonstate terrorist enemies who hide among civilians. The Navy’s role largely has been providing air and missile strikes in support of U.S. troops on the ground. These strikes have been launched from sea bastions, far removed from the battlefield, where avoiding civilian casualties and providing the adversary “off-ramps” from further conflict have helped foster the law enforcement approach.

The absence of a blue-water adversary also has dulled the Navy’s warfighting prowess, and the insufficient numbers of ships in the fleet mean more Navy units operate independently than used to be the case. Today’s watch standers have much less experience than their predecessors in operations in multiship formations—with the dynamic maneuvering and flurry of signals and radio transmissions that require them to be highly proficient in their assignments, to have mastery of the contents of tactical maneuvering and warfare tactical publications, to remain calm under pressure, to be highly organized, and to be able to juggle multiple and competing priorities.

Fix It

Navy leaders have recognized that there is a problem—usually considered the first step to fixing it—and that naval-oriented peer adversaries are on the rise and pose serious threats. But training with the same operating concepts and mindset to fight the last war, even as it continues today, may lead to a quick and humiliating defeat for the U.S. Navy in a future conflict. The Navy must relearn and master the core competencies of a world-class, offensive-oriented blue-water navy in which speed, maneuver, deception, and initiative are paramount. This will require a renaissance in training at the individual officer and enlisted professional levels, as well as at the unit and group levels.

It also will require a return to the schoolhouse to a degree not seen at present. For example, a junior officer who was commissioned in the mid-1980s could expect to attend six months of academics and hands-on practical labs at Surface Warfare Division Officer Course, followed by at least one billet-specific training (BST) course before reporting to his first ship. More BST courses and team trainers would follow during the course of his or her first sea-duty assignment. Enlisted sailors from the same era had a similar experience, with “A” schools and specialty courses prior to and throughout their sea tours. Officers and enlisted personnel did not report to their ships as resident experts, but they did arrive in possession of the core professional fundamentals and theory on which to build competency and depth of knowledge. This allowed them to contribute to mission accomplishment from the start of their tours. The current trend in computer-based, self-paced training at the Navy’s “A” schools is a step in a troubling direction. The Surface Warfare Officers School had gone down this path but has shifted back to more traditional instructional methods after poor results.

In recognition of this knowledge-base shortfall, the surface navy is expanding incrementally the training that ensigns receive prior to reporting to their first ships. Basic Division Officer Course (BDOC) has been increased from its original three weeks to almost six, but it still falls short and lacks the time to do more than “expose” students to topics rather than teaching them in depth. An advanced short course that emphasizes tactical topics is now part of the career track for junior surface warfare officers between their first and second sea tours. Another recent initiative is a pilot three-week Junior Officer of the Deck (JOOD) course to teach shiphandling and navigation to ensigns. Merging these courses with BDOC would better prepare junior officers for duty. BST courses of one or two weeks in length, depending on the topic, also should be reinstated. The physical infrastructure still exists, though it is currently underused (and might disappear in a new round of base closings). In most cases, the curricula already exist in archives, awaiting only review and updates.

At the unit and group level, training must be of sufficient length to provide the repetition and rigor necessary to prepare for naval combat against a peer competitor. When the Navy prepared to fight during the Cold War, refresher training consisted of six to eight weeks of intense damage control, tactical combat vignettes, shiphandling evolutions, and other readiness assessments. The length of time was determined by the performance of the ship’s crew, not an arbitrary date to meet a schedule line item. If a crew performed well, it could complete refresher training in six weeks. If not, the crew stayed until they got it right.

Refresher training was unit-level training, and ships’ crews left with the confidence and skills needed to tackle the next phase of pre-deployment training, which consisted of group-level live, at-sea training and culminated in battle-group versus battle-group events—fleet exercises where tactical leaders and watch standers matched wits and tactics against a thinking opponent. This type of time- and resource-intensive training requires a fleet of sufficient size to source this regimen and still meet overseas commitments. The training should prepare crews for high-intensity naval combat and must be intensive, pushing ships and watch standers hard, and keeping them at sea until they get it right. The tyranny of global deployment schedules drives and limits the scheduling of maintenance and training. A few weeks’ gap in overseas presence should be preferable to deploying a ship not fully ready for combat.

The Navy training community has begun the integration of live, virtual, constructive (LVC) entities—through fleet synthetic training vehicles—into at-sea training and certification events. This is a good step in the right direction, replicating large numbers of friendly and hostile forces. For LVC to contribute to high-intensity training scenarios, it will have to replicate more fully elements of all warfare domains. In addition, procedures and protocols should be explored to mix live forces more closely but safely with virtual ones. More realistic LVC combined with extended time at sea to build proficiency in, rather than exposure to, tactics, techniques, and procedures will go a long way toward better preparing deploying Navy forces for naval combat. To train for high-intensity naval combat properly will not come cheaply. It will require a reprioritization of existing funds and an increase in future funding. It also will require increased fleet size to provide time for adequate training and maintenance without curtailing operational commitments.

Do Not Wait

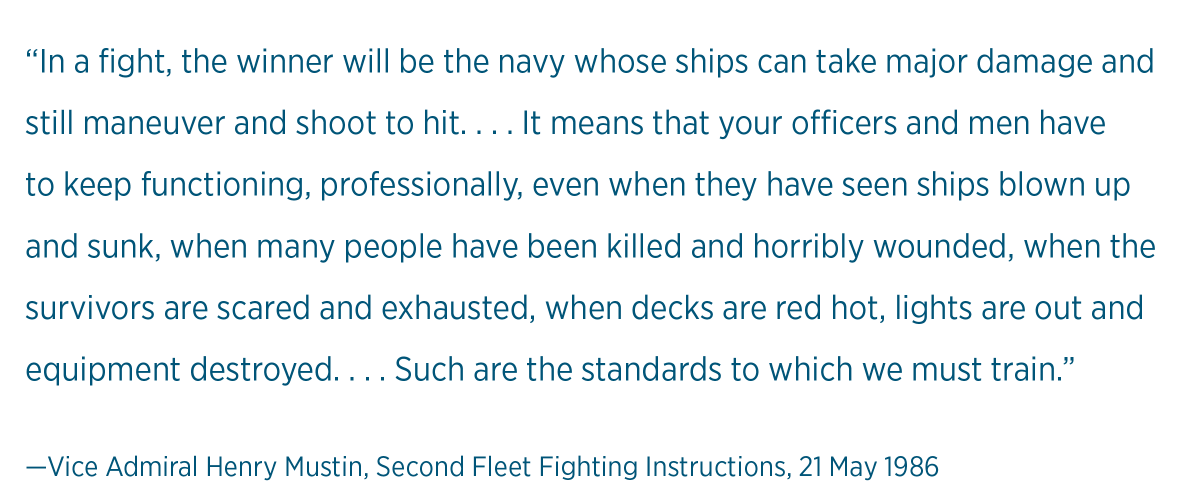

Even without spending any additional money, however, there is much the Navy can do. It begins with a change in mindset. Clear commander’s guidance and intent do not cost a dime. Leaders can offer instructions that will shift the tactical decision makers’ and watch standers’ mindsets immediately from a risk-averse, defensive orientation to an offensive one. Learning how to fight a naval war again will necessitate a servicewide cultural renaissance that emphasizes that the Navy is first, last, and foremost a warfighting fleet, whose purpose is to go in harm’s way and defeat the nation’s enemies. That message was best articulated in late–Vice Admiral “Hammering” Hank Mustin’s 1986 Second Fleet Fighting Instructions. Those instructions laid out the conduct and execution of NATO’s concept of maritime operations with clear and unambiguous guidance, intent, and priorities. It was written in such a way that if a ship’s captain or tactical action officer read only this document and then had no further communication with higher headquarters, he or she would know what to do to complete the mission. Describing operations in what today would be referred to as a communications-denied/degraded environment together with severely restricted own-force emissions in widely dispersed formations, the instructions offer a how-to manual for today’s warfighters facing again the possibility of high-intensity naval combat.

The findings of the recently completed surface force “Comprehensive Review,” directed by Commander, U.S. Fleet Forces, identify many of the systemic issues that are causal factors in the Navy’s warfighting decline. The recommendations for corrective action contained in the report are on point and refreshingly candid about the state of the surface navy and the changes needed to correct its decline. If implemented, they would go a long way toward helping the Navy regain its warfighting professional edge. It is encouraging that the review has been widely disseminated and is easily accessible. In contrast, the February 2010 Balisle Report (“Fleet Review Panel of Surface Force Readiness”)—another no-holds-barred, candid report about the state of the surface navy—was surrounded by secrecy and received very limited distribution. Its findings, also on point, were implemented only partially at best.

In Otto Preminger’s 1965 epic movie In Harm’s Way, Kirk Douglas’ character turns to John Wayne’s in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack and says, “Old Rock of Ages, we got us another war. A gut bustin’, mother lovin’, Navy war!” If today’s Navy woke up to find itself in a similar naval conflict tomorrow, would it know how to fight it?