I remind myself that the military has made great strides in equal opportunity. The “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy is a relic of the past. Women account for more than a quarter of the U.S. Naval Academy’s commissioning class and can choose to serve in every warfare specialty the military offers, including submarines and infantry. By contrast, when I was commissioned in 2007, my options as a female Navy officer were aviation or surface warfare. Today, in Washington, D.C., there exists not only a decades-old Navy Office of Women’s Policy, but also an Office of the 21st Century Sailor, intended to address hot-button issues such as sexual assault, drug and alcohol abuse, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender inclusion, suicide prevention, and diversity. And yet, in 2017, the military cannot decide how best to dress its servicewomen.

Hot-Button Uniforms

We have endured one confusing uniform policy change after another. In 2013, the issue making headlines was hats, called covers in the military.1 It was decided that the traditional dress uniform covers—previously designed differently for men and women—should be more standard. The newly designed women’s cover looked a lot like the men’s cover. The upswept sides and curves designed in the mid-20th century were replaced by a standard duck-bill brim airline pilot or police officer hat.

In 2015, we saw the testing of choker whites for women.2 Choker whites—the iconic high-collared, gold-buttoned look—worn by men in movies such as Top Gun and An Officer and a Gentleman caused their female costars to swoon. Choker whites on women, however, tend to make them look like, well, men.

Newspaper articles that covered the uniform changes included some very cautious quotes from high-ranking officers, stating explicitly that they were not trying to put women in men’s uniforms. They pointed to extensive fit testing and tailoring to make these new uniforms, both hats and choker blouses, fit better than even the old women’s uniforms. There was not, however, any discussion of tailoring women’s uniforms to fit men.

A few months before the spring 2016 Naval Academy graduation, the superintendent decreed that skirts and high heels—traditional optional dress components for military women—would be banned at the commissioning ceremony. Instead, women who graduated in the hallmark 40th year of women at the Academy were compelled to wear trousers like their male counterparts. If I had to guess, the Class of 2016 was more focused on that goal than on what they were wearing when they tossed their hats in the air. Indeed, one Academy senior noted on Yik Yak—an anonymous commenting app popular around campuses—“Skirts or pants, we are still going to be graduating in 94 days.”3

Does it matter what women wear, or do women’s achievements in the military eclipse what appears to be a fashion dilemma in the Pentagon? Another Yik Yak user believes the issue of skirts runs deeper than fashion: “It really isn’t just about uniform standards. I want equality of respect for our character. The misconceived notion is that women must wear a tailored male uniform to receive that respect.”4 A fellow naval aviator echoed this unspoken sentiment among many female officers: “Changing a uniform was a much easier way of handling the situation than taking a deep, introspective look. . . . I’d wear a potato sack, if that’s what the military decided my uniform would be. But I’d love to see my leadership stop paying lip-service to gender issues. They either care or they don’t, and new pants won’t convince me one way or another.”5

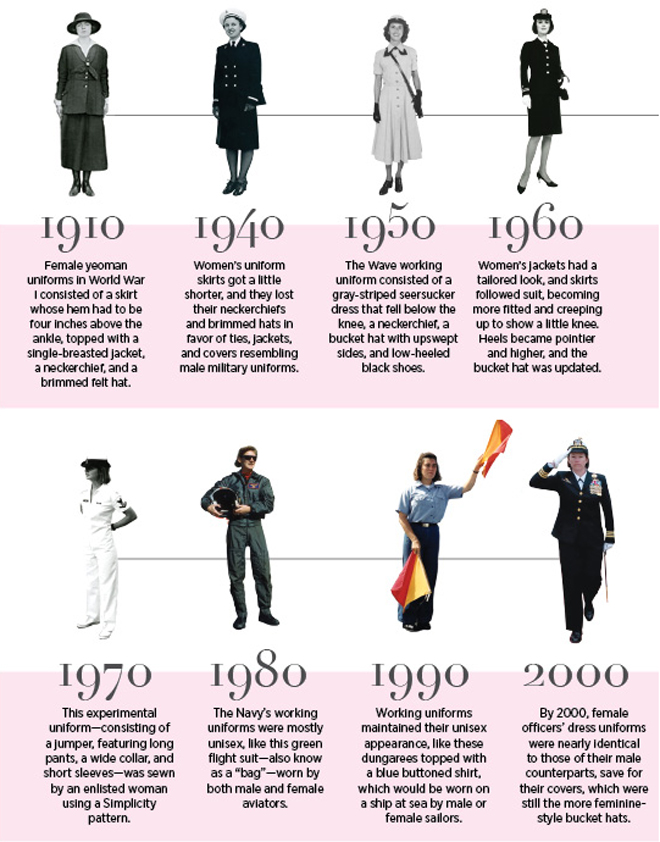

It is worth pointing out that working uniforms worn for warfighting—flight suits, scrubs, camouflage fatigues—are already unisex. The military is attempting to change women’s dress uniforms worn for special occasions or at professional meetings. In the mid-20th century, when dress uniforms were adapted for women, social constructs prevailed over common sense in military clothing design. The recruiting posters for women during World War II depicted attractive, sexy women in uniform. This advertising campaign did not address the broader question of gender integration. It did not address how to preserve sex difference while controlling sexuality.6

Clothes make the Woman

The psychology behind appearance stereotypes runs deeper than the sound advice to dress your best to make a good impression. Research referenced in Psychology Today supports the idiom that clothes make the man—or in this case, the woman.7 Stereotypes about appearance, while influencing careers of women universally, are exaggerated for professional military women. A uniform signifies acceptance, belonging, and respect. It is, according to researcher Cecilia Hock, “a certificate of legitimacy” that establishes both a mindset and an image.8 Appearances project power, and the traditional image of power is masculine. The military for decades has struggled to establish an acceptable image of the ideal woman in uniform without violating gender norms or threatening masculine power. This ideal woman warrior must be a unique blend of feminine and masculine, without sacrificing too much of either.

Professional women entering the workforce often were told to dress for success. In the 1980s, that meant wearing shoulder pads and boxy suits to emphasize masculine power. On the other hand, some companies such as airlines tried to accentuate the femininity of their female employees with dress codes requiring makeup and skirts. Many gender-specific rules concerning appearance were proven unlawful, with courts decreeing “that all dress dimorphisms are essentially and inextricably entwined with the elements of sexuality and power.”9

In the civilian sector, the days of masculine dress are coming to end. According to CEO: Chief Executive Officer, a woman in today’s corporate world does not have to dress like a man to be taken seriously. “Twenty years ago, there were fewer women in the boardroom and they needed to emulate men to get there. That’s where the masculine, built-up shoulders and hairstyles came from. But today, women have proved themselves as equal and there’s no need to copy men. Powerful female executives want to dress to feel feminine.”10

In the military, however, women do not have the option to dress in updated “power suits.” The gendered expectations regarding military dress and the importance of image are much more complicated. Examining the historical arguments about women’s military pants and skirts, and balancing fit and femininity, is critical.

Balancing Fit and Feminity

Prior to World War II, men maintained a monopoly on the military. Many men in the mid-20th century saw women as threatening this monopoly, and the intrusion of femininity into the military domain was met with resentment. While the massive military machine of World War II necessitated women’s service, changing deeply ingrained social norms would prove to be an uphill battle.

The military campaign to recruit women was so focused on maintaining the femininity of female recruits that the services opened themselves up to a so-called Slander Campaign in 1943.1 Ugly, false rumors concerning the loose morality of female service members circulated both in the ranks and in the civilian population, hurting the reputations of these women and negatively affecting morale. The rumors included pregnancy, use of government-issued prophylactics, prostitution, heavy drinking, and other conduct unbecoming proper young women and officers. The rumors were worse among soldiers overseas who had no contact with military women, and the libel grew to the point where the U.S. government investigated whether Axis enemies were behind the campaign. They were not.

After the war, some women remained in the military in a reduced capacity. In the late 1950s, Navy Captain Winnie Collins was surprised to discover that the public viewed military women as unfeminine. As head of all Navy women, she reexamined regulations on hair length, skirt length, and shoe heel height and brought beauticians and hairdressers in to the women’s barracks to reform this view.2

The introduction of women into the all-male service academies in 1976 marked another shift in military culture that many men were unwilling to accept. The uniform the women would wear in this tense environment and its design were integral to the success of these women. Unfortunately, caught between fear of overly masculine women and degrading the inherently masculine nature of the military organization, decisions made concerning female uniforms were abysmal. Femininity was placed over function, as seen with the choice for footwear: “High heels—the ultimate in impractical female footwear—could not be justified in terms of military utility or even neatness of appearance, but women cadets in high heels reassured an institution anxious about the competing image of women in big, black combat boots and fatigues,” says researcher, author, and veteran Elizabeth Hillman.3

The emphasis in uniform regulations for women on presenting a feminine appearance reflects the worry that only mannish—and this implied lesbian—women would apply. Hillman, in her chapter “Dressed to Kill? The Paradox of Women in Military Uniforms,” notes that all-male committees determining regulations were desperately trying to avoid “the worrisome stereotypes of military women as either prostitutes or lesbians.”4

In the process of assuaging their own fears with ill-fitting but “feminine” wear, the leadership did not consider that “in this way women were marked as ‘other,’ while the specifically sexual—or sexually attractive—aspect of that ‘otherness’ was denied.”5 The first service academy women, forced to wear impractical, unattractive heels and skirts, awkwardly stuck out among their male peers. Acceptance was impossible under these circumstances. When the academies did favor slacks over skirts, the slacks fit poorly and emphasized differences in the female anatomy, creating the illusion of wide hips and buttocks even on slim women. Not only do the pants cause many women to appear overweight, but the bizarre sizing conventions also require a size 6 Levi’s wearer to purchase size 14 uniform slacks. Failure to provide clothing that fits and balances practicality and femininity may have contributed to a low self-image among women in the military.

1. Mellissa Ziobro, “Skirted Soldiers: The Women’s Army Corps and Gender Integration of the U.S. Army during World War II,” Army History, 21 June 2016, www.armyhistory.org/skirted-soldiers-the-womens-army-corps-and-gender-integration-of-the-u-s-army-during-world-war-ii/.

2. Winifred Collins and Herbert M. Levine, More than a Uniform: A Navy Woman in a Navy Man’s World (Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 1997).

3. Elizabeth Hillman, “Dressed to Kill? The Paradox of Women in Military Uniforms,” in Mary Katzenstein and Judith Reppy, eds. Beyond Zero Tolerance (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1999).

4. Ibid.

5. Sharon MacDonald, Pat Holden, and Shirley Ardener, eds., Images of Women in Peace and War: Cross Cultural and Historical Perspectives (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998).

Unisex Uniformity

The controversy surrounding covers, neckties, choker whites, and skirt bans is only the most recent evidence of a service-wide campaign to hide gender differences and therefore perhaps unintentionally defeminize servicewomen. The party line from senior Navy leadership is a goal of unisex uniformity throughout the fleet. “Top personnel officials see this as an opportunity to streamline women’s uniforms to better match men’s,”reported Navy Times.11 The slogan “one in dress, one in standard, and one in team” is snappy, but it begs the question, why not adjust men’s uniforms to better match women’s? When this idea was even rumored, the mainstream press erupted with headlines like “Obama wants Marines to wear ‘girly’ hats.”12 The Commander-in-Chief was further accused of an attempt to emasculate the nation’s fiercest warriors. The result of this panic was that female Marines were immediately directed by senior leadership to adopt the male cover as the common uniform hat.

According Kay Sexton, author of A Soldier and a Woman: Sexual Integration in Military, “Women appear to be trapped by the relationship between their appearance and its effects on the male military machine.”13 The military has a history of sending mixed messages to women in uniform, probably because it has yet to determine its own institutional feelings on the subject. While social science research shows that attractiveness is an advantageous trait in the civilian workplace, it is unclear what image is required of a successful military woman. Cynthia Enloe, author of Does Khaki Become You? The Militarisation of Women’s Lives asks: “If women are called upon to soldier, should the government issue them uniforms that declare their ‘femininity,’ at the risk of emphasizing their sexual otherness in an essentially masculine institution? Or should women soldiers wear uniforms designed to hide their sexual identity, to make them blend in with men, thus sacrificing whatever privilege males get from being soldiers and whatever protection women are supposed to get from their ‘vulnerability?’”14 These questions are at the heart of the paradox of the ideal image for female service members.

As a flight-suit-wearing naval aviator—and one of the just 5 percent of Navy pilots who are women—I appreciate the sensibility of the unisex, comfortable, and flame-resistant green “bag,” as flight suits are affectionately dubbed. In flight school, before we students earned the privilege to don our flight suits, I chose the ill-fitting khaki pants over the optional skirt and heels. I was usually the only woman in the classroom, and part of me worried I would not be taken seriously in a skirt and heels.

Tactics Over Trousers

In the wake of the seagoing services’ internal public relations nightmare over the abolishment and then hasty return of sailors’ time-honored ratings, it occurred to me that it is not a skirt or cover that detracts from warfighting. It is the fact that uniform policy changes and the subsequent debate distract from the job at hand. We are having conversations about skirts and unisex covers and gendered titles when we should be talking tactics.

Just before my winging, my Dad removed his father’s gold wings from his white chokers. In the picture taken outside the auditorium in the Florida sunshine after the ceremony, I am smiling broadly with my Dad’s arm around me, wearing our family heirloom wings while shiny new ones decorate my Dad’s chest. I’ve never been prouder, as I am sure my grandfather felt when he first wore the wings in 1944.

I was wearing a skirt.

1. Sam Fellman “Female Uniform Tests Include New Combination Cover,” Navy Times, 23 December 2013, www.militarytimes.com/story/military/archives/2013/12/23/female-uniform-tests-to-include-new-combo-cover/78544426/.

2. Lance M. Bacon, “Navy to begin testing new female dress uniforms at Naval Academy graduation,” Navy Times, 10 May 2015, www.navytimes.com/story/military/2015/05/10/naval-academy-graduation-marks-launch-of-female-sdw-wear-test/26974051/.

3. Christina Jedra, “No more skirts: Female midshipmen to wear trousers at Naval Academy graduation,” Capital Gazette, 24 February 2016, www.capitalgazette.com/news/naval_academy/ph-ac-cn-naval-academy-skirts-0224-20160224-story.html.

4. Ibid.

5. Personal conversations and emails with LT Alyssa Wilson and LT Flannery Woodward (March-April 2016).

6. Sharon MacDonald, Pat Holden, and Shirley Ardener, eds., Images of Women in Peace and War: Cross Cultural and Historical Perspectives (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998).

7. Jordan Gaines Lewis, “Clothes Make the Man – Literally,” Psychology Today, 24 August 2012. www.psychologytoday.com/blog/brain-babble/201208/clothes-make-the-man-literally.

8. Cecilia Hock, “Creation of the WAC Image and Perception of Army Women, 1942-1944,” Minerva: Quarterly Report on Women and the Military, vol. 13, no. I, (31 March 1995).

9. William R. Corbett, “The Ugly Truth About Appearance Discrimination and the Beauty of our Employment Discrimination Law,” Duke Journal of Gender and Law Policy, vol. 14, no.1 (2007), 153-78.

10. Staff writer, “Dress for Success,” CEO: Chief Executive Officer, 13 April 2007, www.the-chiefexecutive.com/features/feature716/.

11. Sam Fellman “Female Uniform Tests Include New Combination Cover.”

12. Jeane MacIntosh, “Obama wants Marines to wear ‘girly’ hats,” New York Post, 23 October 2013. nypost.com/2013/10/23/obama-wants-marines-to-wear-girly-hats/.

13. Kay Sexton, review of A Soldier and a Woman: Sexual Integration in the Military, (No. 143) 2 September 2009, www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/143.

14. Cynthia Enloe, Does Khaki Become You? The Militarisation of Women’s Lives (London: Pluto Press, 1983).