Navy leadership prides itself on keeping fleet manning as one its top priorities. What many on active duty today may not understand, however, that to save costs—under the umbrella of its Optimal Manning Program—in 2002 the Navy changed the number of hours available each week for sailors to work on board ships from 67 to 70 hours. This change to manning calculations reduced the destroyer manning, for instance, by approximately 12 sailors. While many of the changes that supported the Optimal Manning Program have been reversed, this one has remained. According to a May 2017 General Accounting Office (GAO) report (GAO-17-143), the math did not add up then and does not add up now. In Orwellian Animal Farm fashion, the small change went unnoticed, like reducing the amount of corn allotted to each farm animal. The numbers became the new normal, but like in Orwell’s book, they have generated pernicious results over time.

Taken cumulatively since 2002, this three-hour change has had widespread implications ranging from maintenance overruns to crew fatigue. When multiplied by 240,000 enlisted sailors over 15 years, millions of man-hours were added to the shoulders of our ships’ crews. It is time to establish a realistic Navy workweek and assign an adequate number of personnel to each ship to support it. The first step is to reset the “applicable productive workweek” portion of the standard Navy workweek (SNWW) to 67 hours.

The Folly of Optimal Manning

In 2002, a group of action officers and civilians faced a difficult problem. The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) challenged them to create the foundation for the “optimal manning” and other cost-saving programs. The group was given a nonnegotiable number of personnel reductions, no matter how hard they tried, the workload on ships divided by the number of sailors under the new plan did not work.

One can imagine the frustration. Perhaps someone quipped, “I know! Change the number of hours in a day!” We have all at some point had this whimsical wish, often invoked by overloaded workers, new mothers, and college students studying for exams: “If only there were more hours in the day.” With the stroke of a pen, the CNO’s group found a way to achieve the stated goal—adding three hours to the productive work allocation in the SNWW.

OpNavInst 1000.16 states that manning requirements are equal to the “weekly work-hours required” divided by hours available in a “applicable productive workweek.” Previously 67 hours long, the official “denominator” of underway workload calculations was raised to 70 hours with the implementation of Change 1 to the instruction. This—according to a June 2010 GAO study (GAO-10-592)—was done "without sufficient analysis." The GAO study went on to conclude the Navy tends to “overstate the amount of sailor time available for productive work.”

In practice, we know most sailors work far more hours, often 80 to 90 per week or more, and are forced to prioritize what work will get done and what will not. The bad math built into the model exacerbates the problem by allowing the Navy to claim that the fleet is nearly fully manned based on a seemingly innocuous change in the number of hours available week for work.

Studies have shown the enduring negative impact of inadequate manning and reinforced the impact of suboptimal manning calculations. The 2017 GAO study states:

Current and analytically based manpower requirements are essential to ensuring that crews can maintain readiness and prevent overwork that can affect safety, morale, and retention . . . without updating its manpower factors and requirements and identifying the personnel cost implications of fleet size increases, the Navy cannot articulate its resource needs to decision makers.

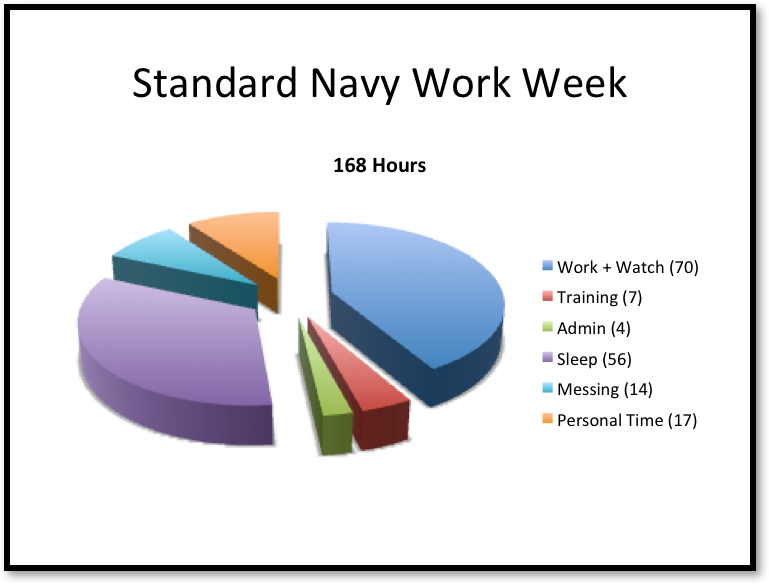

The Navy needs to develop a new model that honestly accounts for manpower requirements. But the math affecting the “numerator” of the manning equation—the calculated workload—is complex and remains difficult to define. One GAO recommendation, however, could be implemented today without any further analysis, and that is to change the denominator back to 67 hours because sailors on ships feel the impact of the higher number every day. The good news is it requires no congressional mandate and no new studies. Broken down, the SNWW looks like this:

1. Work + Watch = 70 hrs. This is based on three-section watch rotation (56 hours) and work (14 hours). While not all sailors stand watch, and there are other factors, the calculation applies to the vast majority of sailors and assumes equivalent workload demands for all crew members at sea.

2. Sleep = 56 hrs. No one is arguing that sailors get too much sleep, and there is plenty of science telling us that we should leave this number alone. (An added benefit to changing the model could allow ships to man four watch sections instead of three, allowing the use of circadian watch schedules, increasing the quality of sleep.)

3. Training = 7 hrs.

4. Admin = 4 hrs. (Probably reasonable—some will disagree!)

5. Messing = 14 hrs. (Two hours for three meals each day——pretty reasonable!)

6. Personal/Sunday Free Time = 17 hrs. (Two hours/day and five on Sunday)

If the Navy restored the hours available for work and watch to 67 hours, the other three hours could be used for:

1. Physical activity. The Navy’s Physical Readiness Instruction, OpNavInst 6110.1J requires two-and-a-half hours of physical activity per week (add 30 minutes for a shower).

2. On the job training (OJT).

3. “Block” learning—travel, PQS, OJT—under the Sailor 2025 program.

4. More free and personal development time—for a whopping 20 hours per week.

Changing the hours available for work section—the denominator—of the NSWW to use 67 hours likely would result in a 4 percent increase in the manning requirements of a ship—with the eventual result that when the manning demand signal increases, additional sailors follow, albeit a few years later.

Toward A Reasonable Work Week

As the June 2017 GAO study explains, “The fleet is projected to grow from its current 274 ships to as many as 355 ships, but the Navy has not determined how many personnel will need to be added to man those ships.” Now is the time to update the 15-year-old manning model and shorten the hours of productive work available in the Standard Navy Work Week to a more reasonable 67 hours.

Captain Cordle retired in 2013 after 30 years of service. He once served as the Director of Manpower and Personnel for Commander Naval Surface Forces Atlantic. He commanded the USS Oscar Austin (DDG-79) and USS San Jacinto (CG-56). He is the 2010 recipient of the U.S. Navy League’s Captain John Paul Jones Award for Inspirational Leadership.