This article by Alan L. Morse originally appeared in the February 1984 issue of Proceedings.

What's in a nickname? Today's Goodyear Blimp was named after the fat, fictitious Colonel Blimp of British cinema fame. But one of its ancestors – the World War I kite balloon – was whimsically christened the "rubber cow," and went to sea tethered to a "tin can."

They were the least glamorous of World War I pilots. Their aircraft were unlovely, unromantic, uncomfortable, and unpowered. They fought no aerial duels with the Red Baron nor skimmed the trees on reconnaissance missions. These pilots never fired a shot at the enemy, because they never carried guns, and yet they played a major role in the winning of the Great War.

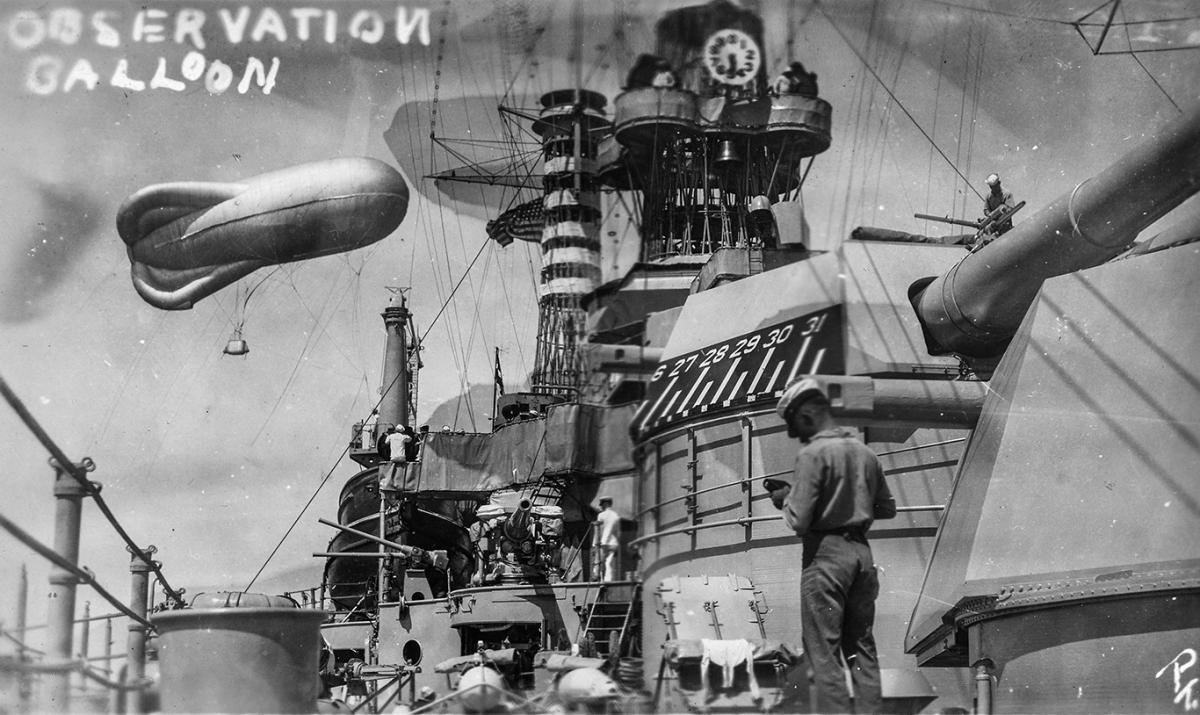

They were the U.S. Navy's "eyes in the skies," seagoing kite-balloon pilots. They flew in balloons tethered to destroyers that went to sea and rendezvoused with convoys. Those kite-destroyer units escorted convoy after convoy of merchantmen through enemy submarine zones and saw them safely into Allied ports. More than two million troops crossed the sub-infested Atlantic successfully because of the Navy's escort operation. From their baskets high above the ocean, the kite pilots spotted lurking U-boats and guided destroyers to drop depth charges and sink them.

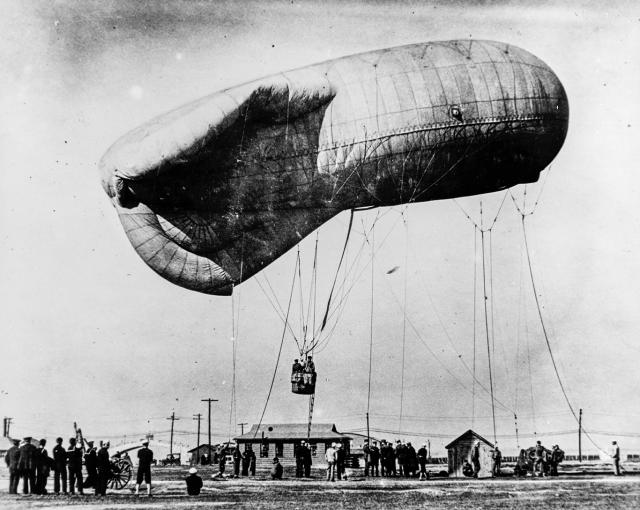

The use of kite balloons for spotting U-boats proved to be so successful that all destroyers on escort and patrol duty would have been towing them if not for the shortage of pilots. To supply this deficiency, an emergency balloon-pilot training program was established at Goodyear's Wingfoot Field in Akron, Ohio; by October 1917, 23 blithe young rookies had reported for duty. They attended ground school, served as handling crews, and were taken on training and solo flights in big, free-drifting spherical balloons. Then the pilots went on to fly in the kite balloons and became intimately familiar with their characteristics. These balloons came to be known affectionately as "rubber cows."

The last kite-balloon training flight that year was made late in December. Two trainees were let up into a howling, blinding blizzard with gale-force winds and a near-zero temperature. The wind screamed, the fabric cracked, and the low-hung basket all but tore itself loose. The snow built up on the kite's nose and drove into its air scoop. It jerked and jerked on its cable as it plunged and pitched. It was a punishing storm, but balloon rode it out and the cable held. Those rubber cows may not have been beautiful, but they were very tough.

At the Rockaway Naval Air Station, the Navy tested a new parachute arrangement for kite balloons. The pilot had only to pull down on an overhead lanyard, and he and the basket were on their way down. As they fell, a big parachute was jerked out of a box-like container that hung in the rigging. The 'chute popped open and afforded a swaying, swinging descent to a knee-buckling landing.

The "basket-dropper" passed its tests cum laude. Nevertheless, the conventional pilot-only parachute was preferred for use at sea. It was packed in a flat container that hung on the front of the basket, with a shroud line that dipped into the chest ring of the pilot's parachute harness. In case of an emergency, the pilot had only to dive overboard. His falling body jerked the 'chute out of its container, and the pilot descended to a cold, wet splashdown.

On 31 January 1918, kite-balloon trainees were detached from Rockaway, commissioned as ensigns, and about a month later took passage for Liverpool, England, on board the passenger liner St. Louis. With her 20-knot speed and three 6-inch guns, she was a match for any U-boat. The crossing was smooth, and on 6 March, 23 shiny-new ensigns stepped ashore in Liverpool.

Their journey was far from over. Shortly after they landed, the pilots were on a train bound for Holyhead on the coast of Wales. They crossed the Irish Channel on board a fast packet ship and landed near Dublin, Ireland. From there, they traveled again by train to Queenstown on the southeast coast. There, they reported to Commander F. R. McCrary, who assigned them to bases in Ireland, England, and France for duty as kite-balloon pilots on convoy-escort missions.

An escort mission started when a destroyer moved into the air-station dock and blasted its siren. A kite balloon was then transferred from its shore cable to the destroyer's tether cable and was let up a few hundred feet with an empty basket. Then the pilot boarded the ship, checked in with the skipper, and stowed his gear while the destroyer headed out to sea with her balloon.

On one such mission, the destroyer had scarcely cleared the breakwater when she ran head on into a roaring, screaming gale. She was tossed and battered by the crashing seas and lashed by the driving rain. Her foredeck was awash with green water, while her balloon yawed, plunged, and jerked above on its cable like a crazed animal. Cooking was impossible, and the crew subsisted on "tinned Millie" and other cold rations. Their wet clothing and the constant reek of fuel oil aggravated their discomfort. For the pilot, his rough sleeping accommodations added to his travail. On a crowded destroyer, there were no spare cabins for a balloon officer, so he spent his nights strapped to a transom in the wardroom, where did little sleeping. Each time the ship pitched, the transom dropped away from under him; he then met it on its way back up while he still was going down.

It was dark when the skipper contacted his particular convoy, so he took station a cable's length to port of the lead ship while the kite rode out the storm aloft. Well before daybreak, it was hauled down close to the deck and brought into wild air turbulence aft of the stacks, where it started diving, first on one side of the ship, then on the other. With each dive, the basket scooped into the water and then was jerked out with a snap. From time to time, however, there occurred brief smoothness, when everything rode on an even keel.

It soon would be daylight, and the pilot was standing by to make his transfer from the deck of the destroyer to the basket of the kite balloon. His boarding line went up through a pulley in the kite's rigging above the basket, then dropped back down to the deck. He clipped his end into the chest ring of his parachute harness, four husky sailors laid hold of the deck end, and all was ready. When the next smooth period occurred, he nodded his head, the sailors walked away with the line, and up to the basket he went. It was not unusual for him to be dunked while making his transfer but, wet or dry, he spent the entire day aloft on the lookout for enemy submarines. A U-boat's periscope was almost impossible to spot from a surface craft. But aloft in his "rubber cow," the pilot could even see the submerged hull. And so he held the balance of responsibility for the safety of the convoy vessels and the lives of their crews. Balloon pilots were keenly aware of this responsibility and forced themselves to remain rigorously alert, no matter how long they stood watch in their baskets or how miserable the weather.

When a pilot spotted a lurking U-boat, he telephoned the bridge of his destroyer via the insulated core of his tether cable, and immediate action followed. Three wailing screams of a destroyer's siren warned the convoy and other escort units, and the chase was on. If the U-boat, aware that she had been seen, attempted evasive action, it was often too late. The pilot guided the destroyer so she could drop her depth charges right over the target and destroy the U-boat.

To get back on board ship, a kite-balloon pilot used the "going up" procedure in reverse. However, there usually was an added element of danger: darkness. The black, cold ocean seemed to reach up for a pilot's basket when it dropped into the water, and the snap upward into the air seemed particularly vicious. The heaving destroyer's deck seemed to be an indistinct blur to the pilots. They could only hope for the best when bailing out, but somehow they managed to drop onto the deck.

For the kite-balloon pilots, World War I was an endless succession of escort missions—out to sea for a few days, back ashore to recuperate, and then out to sea again. When being towed by a destroyer, one day was much like another. Pilots faced the same grim moments of appalling hazard and endured continuous discomfort. However, they survived and returned home safely—all but one.

It happened on 14 August 1918 with a convoy on its way to Liverpool. A balloon pilot had been aloft all day. It was dark and stormy when they hauled him down and his balloon started diving, first on one side of the ship and then on the other. His basket was scooping into the water and jerking out while he struggled to hang on, but suddenly the basket was empty. On that night, one heroic pilot who went aloft in the "rubber cows" drowned in the cold Irish Sea.