At the outset of the Korean War, the U.S. Air Force quickly achieved air superiority over North Korea’s antiquated air force. The U.S. Navy followed this trend, with its new F9F Panther jet fighters shooting down two Yak-9s during the first naval air strike of the war on 3 July 1950.1 As summer gave way to fall, Navy aircraft flew unopposed over Korea, only worrying about the always dangerous anti-aircraft guns on the ground. By now, there were three carriers on station: the USS Leyte (CV-32), Valley Forge (CV-45), and Philippine Sea (CV-47). On 30 September, signs emerged that the game was beginning to change. One of the Philippine Sea’s F4U-4 Corsairs from VF-113 spotted an ominous sight 30 miles northwest of Seoul: a Russian-built MiG-15.2

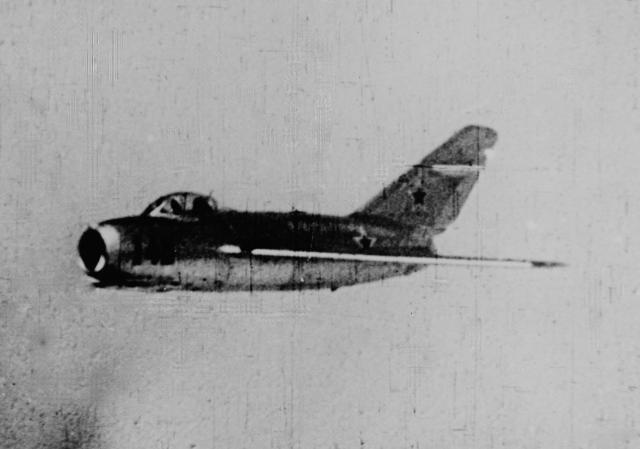

The MiG-15 was a new and somewhat unknown fighter that made use of captured German research in its swept-wing design. No matter their secrecy, the MiGs soon would become a common sight to Navy pilots, for November would see the Navy tasked with destroying the bridges at Sinuiju, from which across the Yalu River lay Manchuria, and the major MiG-15 base at Autung.

On 9 November, a joint strike on the bridges spanning the Yalu River by Carrier Air Group Five (CVG-5) and Carrier Air Group 11 (CVG-11) was carried out with air cover provided by the air wings’ respective Panther units. Lieutenant Commander William T. Amen, commanding officer of Fighter Squadron 111 (VF-111), was one of the Panther pilots covering the strike from the Philippine Sea. Before their 0904 launch, Amen borrowed F9F-2B BuNo 123454 from sister-squadron VF-112. The prop aircraft took off first, and the F9Fs stayed behind to launch later so they could provide well-timed coverage for the prop aircraft on their ingress, time over the target, and egress. This was accomplished using 12 F9Fs separated into three divisions of four aircraft apiece.

Amen was the leader of a TARCAP (target combat air patrol) division orbiting 4,000 feet over the Yalu. While looking for bandits, Amen’s division was alerted to a fast-moving jet approaching from astern. Without the slightest hesitation, the Panthers turned to meet the threat and spotted a silver MiG-15. The MiG was faster, but as the Panthers fired short bursts, the MiG made turns allowing the F9Fs to close the gap. The MiG then went into a dive and Amen followed him down, firing all the way. When his subsonic Panther began to buffet from the speed, Amen ceased shooting and pulled up with only 200 feet to spare as the MiG flew into a hillside.3

The pilot of the MiG, Captain Mikhail F. Grachev, was the first MiG-15 loss admitted to by the Russians. A U.S. Air Force F-80C flown by 1st Lieutenant Russel Brown claimed a MiG-15 on 8 November, but Russian reports state that all MiGs returned to base on that particular intercept mission. If true, then Lieutenant Commander Amen would have scored the first jet-vs.-jet kill not only for the Navy, but the first in history.

The mission was not without difficulty, for VF-111 also came extremely close to losing one of its own to the MiGs. Ensign John D. Omvig was targeted at such close range by one marauding MiG “that the tracers seemed to be going through, instead of around his aircraft” according to a mention of the combat in the cruise book.4 Omvig and his F9F-2B were able to return to the Philippine Sea without issue.

(U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)

After the first encounter with the sleek MiGs on 9 November, the swept-wing adversaries would interfere with almost every subsequent Navy strike on the Yalu bridges for the following week. On 10 November, Panthers from VF-112 were heavily engaged with four MiGs, and the naval aviators nearly fatally damaged one MiG. VF-112 CO Lieutenant Commander John L. Butts with his division composed of Lieutenant Robert E. Chilton, Ensign Ronald E. Aslund, and Ensign Alan E. Hill engaged the nimble swept-wing jet and scored hits along the fuselage, holing its fuel tank. The Panthers’ guns then froze in the extreme cold before the final blow could be delivered. A mention of this combat in the cruise book echoes the mood of VF-112’s aviators that day: “We waited over four months to demonstrate our talents in this particular pastime but, alas! We did not bring home any kills . . . Skipper and Auz were close enough to club one MiG but old man weather proved to be a foe of equal skills.”5

Two days later on 12 November, the MiGs rose again to counter a bridge strike, conducted this time by the Leyte’s air group. As the strike aircraft began their runs, 12 MiG-15s swooped down to ravage the attackers. VF-31, which had two divisions of F9F-2s up above on TARCAP, promptly dove into the MiGs with their altitude advantage. The first division was led by Lieutenant Kelly, and the second division was led by Lieutenant Davidson. The Panthers quickly used up their altitude advantage and began a 25-minute turning fight with the enemy jets. Multiple Panthers got within firing range only to find that their guns were frozen, the same problem VF-112 experienced on 10 November. Nevertheless, the Panthers accomplished their mission of not allowing any MiGs to get a clear shot at the Skyraiders or Corsairs.6

Things reached a head on 18 November, when aircraft from CVG-3, CVG-5, and CVG-11 were engaged by multiple groups of MiG-15s operating from across the Yalu River throughout the day. On this day, VF-52’s CO, Lieutenant Commander William E. Lamb, who already had six kills from World War II, and Lieutenant (junior grade) Robert E. Parker shared the credit for one MiG kill. Lamb remembers:

We were giving cover to our strike below at Sinuiju when the MiGs started making a series of fast passes at us, firing as they came. One of them passed directly in front of Parker and myself, full in our sights. We both fired but doubted that we had hit him until we saw him smash into the ground, making a mushroom explosion where he hit.7

Other pilots from Valley Forge’s air group confirmed the kill as well, watching the MiG disintegrate as it flew back to Manchuria before impacting the ground.8

The Leyte’s TARCAP F9Fs also made strides that day by downing one MiG and damaging another. Directly after VF-32’s Corsairs had finished attacking their targets and VF-33’s F4U-4s were beginning their runs, a frantic call came from a VA-35 AD-4 Skyraider pilot near the target: “Bogeys! Eleven o’clock high!” Fourteen contrails were spotted at 30,000 feet approaching from the Chinese side of the Yalu. A TARCAP of eight F9F-2 Panthers from VF-31 was airborne over the Korean side of the Yalu. The first division was led by VF-31’s CO, Commander George C. Simmons, who at the sight of the MiGs promptly radioed to his flight, “Tally-ho! Let’s take ‘em boys!”9 The second division was led by Lieutenant Davidson, who already had experience with the MiG-15s from the dogfight on 12 November.

VF-31's Panthers met the MiGs head-on and roared through the enemy formation. During the ensuing melee, the straight-wing F9Fs were easily able to out-turn their adversaries. This allowed one pilot, Ensign Frederick C. Weber, flying F9F-2 BuNo 125136, to cut inside the MiG-15 flown by Senior Lieutenant Arkady I. Tarshinov. Tarshinov, who was abandoned by his wingman, frantically tried to throw off his pursuer, but the young ensign would not be denied. He remained glued to Tarshinov’s six o’clock as the MiG pulled up sharply and was hit in the fuselage with 20mm rounds. The MiG then quickly dove to the right before twisting back up and to the left. The MiG, wounded, and probably its pilot too, straightened out and was finished off by Ensign Weber’s cannon. Tarshinov’s MiG plummeted uncontrollably out of the fight and into the Yalu.

Lieutenant Davidson also scored hits and damaged an additional MiG in the dogfight. Spooked in the face of such an aggressive defense and low on fuel, the remaining MiGs turned for home without inflicting any damage on the strike group. Senior Lieutenant Tarshinov’s MiG was the only loss recorded by the Russians on that date.10

U.S. Navy F9F Panthers tallied nine air-air kills over Korea by the end of the conflict. Besides the two Yak-9 kills from July 1950, the rest of the kills were against MiG-15s. Six out of the seven MiG kills were confirmed by both sides, with VF-52's MiG kill on 18 November 1950 being the sole outlier. The MiG in question just happened to cross paths with two Panthers whose pilots were on the ball and ready. The eight combined 20mm cannon of the pair of F9F-3s threw a volley of fire at the MiG, but even the lead Panther pilot, VF-52 CO’s Lieutenant Commander Lamb, doubted the rounds hit their mark. It was only after some Valley Forge Skyraiders and Corsairs reported that the MiG was disintegrating and losing altitude did the Panther pilots see the mushroom cloud it caused as it impacted the ground. This may or may not actually have been the same MiG, if a MiG at all, but the fact stands that the Panther pilots were ready at a moment's notice. If the MiG had passed by cleanly, it would have been possible for it to dive on the strike aircraft below. In a dynamic and contested aerial environment, when seconds mean the difference between mission success and failure, the attentive Panther pilots proved their mettle.

This aerial combat in November 1950 between the Panthers and MiGs is often overlooked but contains many lessons that should not be forgotten. First, the F9F’s success against the MiG-15 stemmed solely from the Navy’s ability to consistently send up well-trained pilots, many with experience from World War II. It was these World War II veterans who pioneered naval jet operations and led the younger aviators in the successful MiG encounters. The MiG, although superior to the F9F in almost every fashion, was consistently singled out and gunned down by divisions of F9Fs working together. The MiGs entered the fights organized, but often separated and went after their own targets, exposing themselves to the Panthers’ guns.

Secondly, the confidence of the Panther pilots is of heightened importance in this case. Naval aviators are trained to be ready for the unknown, but in 1950, no one would have predicted the MiG-15 and the mark it quickly left on the air war over Korea. The Navy had been drastically reduced in terms of manpower since the end of World War II and was not at the forefront of technology. The F9F Panther was a new jet aircraft; however, it retained straight wings to aid in carrier operations. Russia and the U.S. Air Force specifically had adopted swept-wing technology and developed aircraft that took advantage of it while Navy designs were held back in this crucial period of time. Even with these disadvantages weighing heavily on the minds of the aviators, they always dove into the fights with MiG-15s without hesitation, stuck to their training in the face of a much better-equipped adversary, and consistently came out the victor.

Indeed, our current generation of naval aviators also may face a similar situation in the coming decades as threats, especially those from China, expand in the Indo-Pacific region. Without a doubt, the current maritime strategy has pushed the Navy to the frontlines of the expanding Indo-Pacific battlefield. Naval aviation, as has been proven time and time again, will be first responders when the conflict arises, with the men and women of Japan-based CVW-5 most likely the literal first responders in terms of naval air power. One hopes that a surprise like the MiG-15 that shook up the order of battle so heavily does not appear again—but if it does, we must stick to our training, retain our confidence, and meet that threat head-on, just like the Panther pilots of November 1950.

1. Jim Burridge, “Len Plog and the Real Yak Killer,” Naval Aviation News, May–June 1997.

2. USS Philippine Sea CV-47 (Nashville, TN: Turner Publishing, 1999), 20.

3. Barrett Tillman and Henk van der. Lugt, VF-11/111 'Sundowners' 1942–95 (Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2012).

4. Carrier Air Group 11 (CVG-11) Korean Cruise Book 1950–51, 14.

5. Carrier Air Group 11 (CVG 11) Korean Cruise Book 1950–51, 25.

6. History of Fighter Squadron THIRTY-ONE, 1 July to 31 December 1950, 6.

7. War News: Aboard the USS Valley Forge in Korean Waters, November 1950, 29.

8. Richard Hallion, The Naval Air War in Korea (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2011), 75.

9. Adam Makos, Devotion: An Epic Story of Heroism, Friendship, and Sacrifice (New York: Ballantine Books, 2017), p236.

10. Leonid Krylov et al., Soviet MiG-15 Aces of the Korean War (Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2008).