Although often overshadowed by the high-seas exploits of the U.S. Navy’s first six frigates, command and control of the inland waterways was at least as important to the early United States, if not more so. The easiest routes into the U.S. heartland for British forces massed in Canada passed across the Great Lakes—particularly Ontario and Erie—and down Lake Champlain.

In The Naval War of 1812, Theodore Roosevelt wrote of the Great Lakes: “What was at that time the western part of the northern frontier became the main theatre of military operations . . . [with] the command of the lakes being of the utmost importance.” Roosevelt noted that the operations there “properly belong” to naval and not military history. On the high seas, the Royal Navy boasted more than 30 times the number of U.S. Navy warships; on the lakes, however, the forces were in virtual parity, with most of the ships from both sides based on Lake Ontario.

In 1809, the United States repealed the disastrous Embargo Act of 1807 and replaced it with an embargo aimed specifically against France and Great Britain. Enforcing an embargo on the lakes, however, was impossible without ships. In the summer of 1808, President Thomas Jefferson’s administration decided to establish a naval presence on Lakes Ontario and Champlain by building one gunboat on the former and two on the latter.

Navy Lieutenant Melancthon Taylor Woolsey accepted responsibility for building the first U.S. Navy warship on the Great Lakes. The Navy negotiated a contract for $20,505 with New York City shipbuilders Henry Eckford and Christian Bergh to build the ship at the outlet of the Oswego River into Lake Ontario. There, the settlement of Oswego, New York, consisted of little more than two dozen houses and the ruins of old British Fort Ontario. The area had no infrastructure to support the ship’s construction other than the raw material of virgin forests. Arriving carpenters, blacksmiths, and shipwrights hailed primarily from New York City.

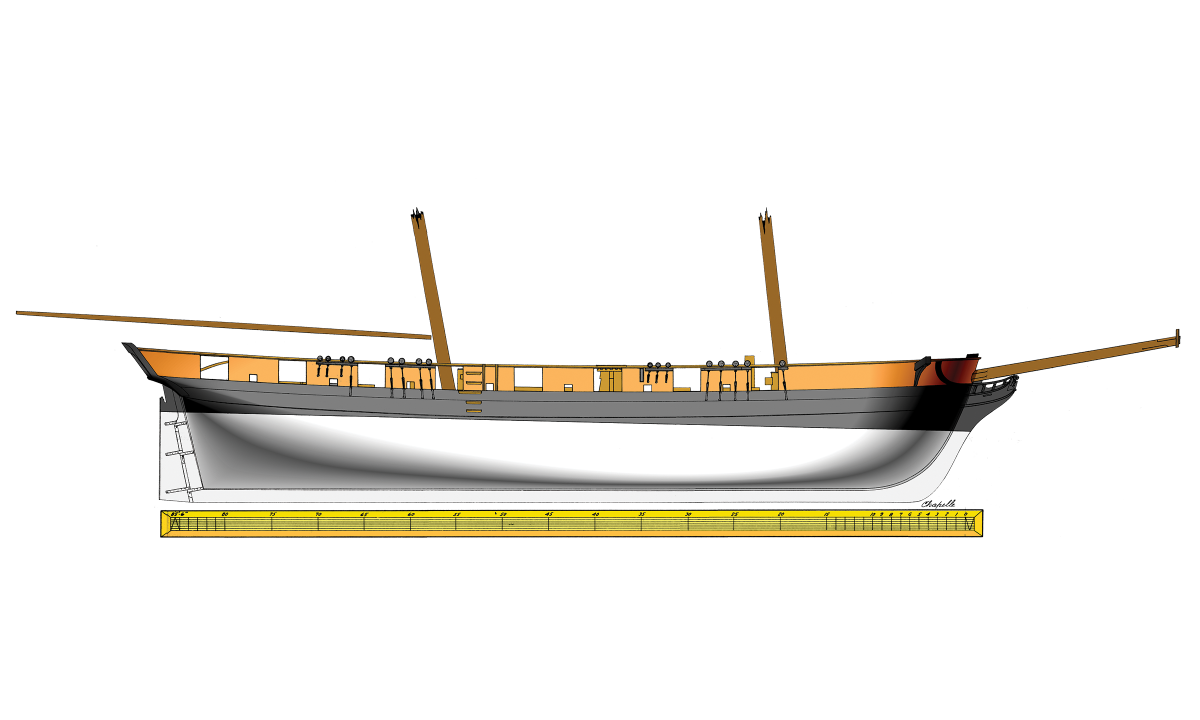

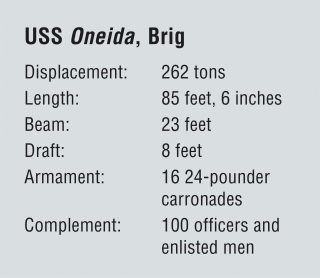

On 31 March 1809, the Oneida, a 16-gun brig, was launched. She proved a good sailer, but after fitting out she was laid up in ordinary. Over the following winter, ice built up on the lake and dammed the river, floating the ship out of her mooring and pushing her ashore. She remained there until late the next summer with irreparable harm to her sailing qualities.

After being commissioned in the fall of 1810, she moved 40 miles to the north-northeast, to Sackets Harbor, New York. Woolsey had chosen the little hamlet as the only suitable available location for a naval station on the lake. The Oneida’s launching spurred something of an arms race on the lakes that would not end until 1815. The Canadian governor ordered construction of two larger warships: the sloop Royal George, at Kingston, at the far eastern end of Lake Ontario—just 35 miles from Sackets Harbor—and the sloop Queen Charlotte, at Amherstburg, at the far western end of Lake Erie.

In April 1812, President James Madison implemented a 90-day embargo, which further raised international tensions, as a final warning to Britain to lift its restrictions on American shipping. Early the next month, the Oneida left Sackets Harbor searching for violators. On 5 June, she seized the British schooner Lord Nelson and returned with the prize. War was declared less than two weeks later, on 18 June, and the next day, a British squadron led by the Royal George attacked the U.S. port.

The Oneida, being “such a dull sailor that it was useless for her to try to escape,” anchored near a bank to cover the harbor entrance. Her offside guns were landed and mounted on shore. After “a desultory cannonade” of about two hours, the British broke off the attack and returned to Kingston, thus ending the First Battle of Sackets Harbor.

The brig’s next action began on the evening of 7 November, when, under command of the newly named inland navy commodore, Isaac Chauncey, she left Sackets Harbor with six converted merchantmen to hunt down British convoy ships carrying supplies to Kingston. The next morning, they spotted the Royal George and began a chase. She sailed west into the Bay of Quinte, where, with night falling, the Americans lost her. While in the bay, however, the Oneida discovered the schooner Two Brothers undergoing repair and set her on fire. During the night, the Royal George slipped past the squadron and made it to the Kingston Channel, where she was spotted the next morning, the 9th.

As the pursuit continued, the Oneida captured the schooner Mary Hatt and sent her to Sackets Harbor as a prize. The squadron chased the Royal George into Kingston Harbor where, for almost two hours, the Oneida exchanged shots with her quarry and shore batteries until night fell and she broke off the action. In his war history, Roosevelt claimed the British sloop suffered extensive damage and “some of her people deserted her.” U.S. losses were light, with one man killed and three others wounded—all on board the Oneida. The next day, amid a storm, the squadron forced the schooner Governor Simcoe aground on a shoal, which later caused her to sink. The squadron returned to Sackets Harbor the next day.

Roosevelt was unrelenting in his criticism of the British. “The Canadian commanders, however, utterly refused to fight; the Royal George even fleeing from the Oneida, when the latter was entirely alone, and leaving the American commodore in undisputed command of the lake.”

For the remainder of the war, the Oneida served as an escort and conveyance for troop landings. On 25 April 1813, she set sail from Sackets Harbor with a squadron transporting 1,700 troops—several hundred on board the Oneida—under the command of Brigadier General Zebulon Pike to York (present-day Toronto), Canada. Two days later, the town was captured, despite the death of General Pike. On the night of 26 May, the Oneida once again embarked troops and artillery and sailed with the squadron for Fort George at the mouth of the Niagara River. The fort was taken the next day. On 27 July, she returned to York to liberate prisoners and seize provisions.

Later that year, the Oneida operated from the Niagara River at the western end of the lake. Into November, the brig served as a protective force for Major General James Wilkinson’s troops at the eastern end, around the St. Lawrence River, before returning to Sackets Harbor for the winter.

By 1814, the Oneida was decidedly an inferior ship. New construction at Sackets Harbor over the previous two years had displaced her. She was disarmed and rode at anchor in the harbor. In March 1815, the commodore reported to the Secretary of the Navy that the Oneida was “quite rotten and in the course of two years would be condemned.” On 15 May, she was auctioned off but only received a bid of $1,760. The Navy repurchased the ship and used her as a troop transport through the end of the year. From that winter, she was virtually abandoned at her long-time home port. The Navy retained the rotting ship for another decade before selling her on 3 March 1825—two years after she had sunk.

By the end of May 1826, she had been raised, refitted, and registered as a merchant vessel named the Adjutant Clitz. The last official record of her still in service is dated 1836. She was reported as having sunk at Clayton, New York, in 1837 and once again in 1838. But one newspaper report from July 1840 indicated she still was active.

Roosevelt wrote an unsparing epitaph for the brig. “The [General] Pike and Madison were fast, weatherly ships; but the Oneida was a perfect slug, even going free, and could hardly be persuaded to beat to windward at all.” Despite that pronouncement—and most likely fact—the U.S. Navy brig Oneida saw more combat against the British than any other U.S. warship during the War of 1812.