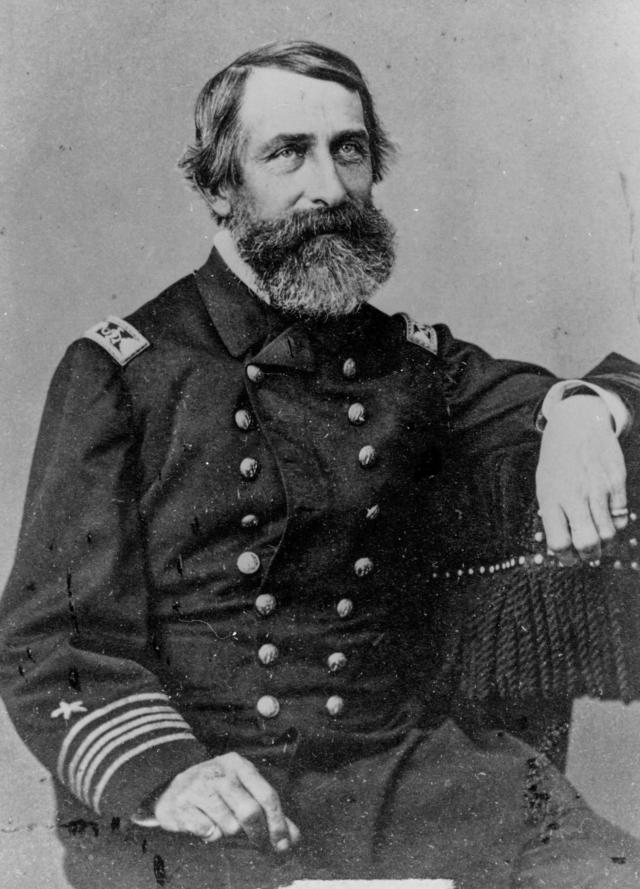

The influences of several generations of officers who shaped the practices and doctrine of amphibious warfare are well known to scholars of U.S. Marine Corps history. Especially noteworthy are the contributions made by Lieutenant General John A. Lejeune, to whom historians generally give credit for transforming the Corps into the modern amphibious force we recognize today. No mention is made of Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren’s influence on the evolution of this field of naval warfare.

Dahlgren is known to most historians as an inventor and a Civil War–era naval officer, but his vision of using sailors and Marines as a landing force featured elements found in modern Marine Corps amphibious doctrine. He not only put his ideas on paper, but also applied them during the Civil War. His views of an exclusive and coherent amphibious unit with prescribed doctrine are at the core of the principles the Marine Corps implemented decades later and perfected during World War II.

Weapons for Landing Forces

John Dahlgren, like most naval officers, spent much of his career at sea, but less than many of his contemporaries. During his extensive pre–Civil War service ashore, he developed new ordnance for the Navy. His most famous invention, the Dahlgren gun, was the most common cannon mounted on board U.S. Navy ships during the Civil War.

In 1857–58, he commanded the ordnance sloop Plymouth for two cruises as a gunnery-practice ship. His goals were to standardize training for gun crews and test his Dahlgren guns for shipboard use. On board, Dahlgren also developed ideas for the use of Marines and sailors ashore. During the Civil War, he rose to the rank of rear admiral and commanded the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron from 1863 to 1865.

Dahlgren, wishing to pursue his ideas on amphibious operations, issued orders to his squadron’s commanding officers to exercise and drill their men with small arms for service ashore. He also prescribed that members of naval landing parties use another of his inventions: the Model 1861 Navy rifle, more commonly known as the Plymouth rifle, which had been designed and tested while he commanded the Plymouth. Based on a French design, the 50-inch-long weapon fired a .69-caliber Minié ball or a load of buckshot. It could accommodate a short, broad-bladed bayonet or a longer sword bayonet, depending on circumstances.1

Dahlgren designed a boat howitzer specifically with amphibious operations in mind. Several 12-pounder versions were eventually produced, as well as a 24-pounder. The guns could be mounted on carriages at the bow of launches and then quickly remounted on wrought-iron field carriages, which were designed to be pulled by about a dozen men using a drag rope.

The admiral’s manual for their use instructed that the howitzers be organized in batteries of three sections of two guns each. Four smoothbore and two rifled 12-pounders would compose each battery. Dahlgren did not foresee that a landing force would use these guns massed in large numbers, instead believing that mobile artillery was more effective. He also believed that by dispersing his guns in combat, his men would be less exposed to enemy counterbattery fire.2

Inauspicious Beginning

Dahlgren first put his ideas to work in July 1863 during the Morris Island siege operations near Charleston, South Carolina. Mounting Union losses, combined with the Army’s increasing fears of Confederate counterattacks, spurred the admiral into action to help end the siege. Dahlgren decided to organize three naval battalions—one composed of Marines and the other two of sailors—to serve ashore to assist with operations. Marine Major Jacob Zeilin commanded the Marine battalion. The Navy Department sent Dahlgren about 260 men, and he also stripped as many servicemen as possible from blockading ships to form the command.3

The sole purpose of this 500-man force was to make quick amphibious landings. The admiral instructed Zeilin to clothe his men comfortably for the hot climate, to divest them of extra baggage, and to carry cooked rations as well as buckshot for close action. Dahlgren provided a detail of boats to land the force and four boats each armed with a howitzer and a field carriage to cover the landings.4

After only a week ashore, Zeilin wrote Dahlgren that the plan to forge a coherent fighting force from his Marine unit was not progressing well. The major reported that his men, who were accustomed to the organization on board ships, had never participated in large-unit maneuvers. Many of the Marines were raw recruits removed from Northern receiving ships and sent south. During their week ashore, the heat and the collateral duties of soldiering such as cooking interfered with drills. Zeilin thought it would be hazardous to use his Marines in an assault until he could drill them extensively and they learned discipline. Only then did he believe they could perform under fire with “coolness and promptness.” This news distressed Dahlgren, who wrote with despair in his diary: “Rather hurtful. What are marines for?”5

He did not forget these problems and would implement improved doctrine and training for the next mission. In June 1864, Dahlgren wrote Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that he would train the Marines with muskets as “light infantry” so they could serve as “sea infantry.” The admiral believed this would make them more serviceable while allowing them to retain their identity when operating with Army units.6

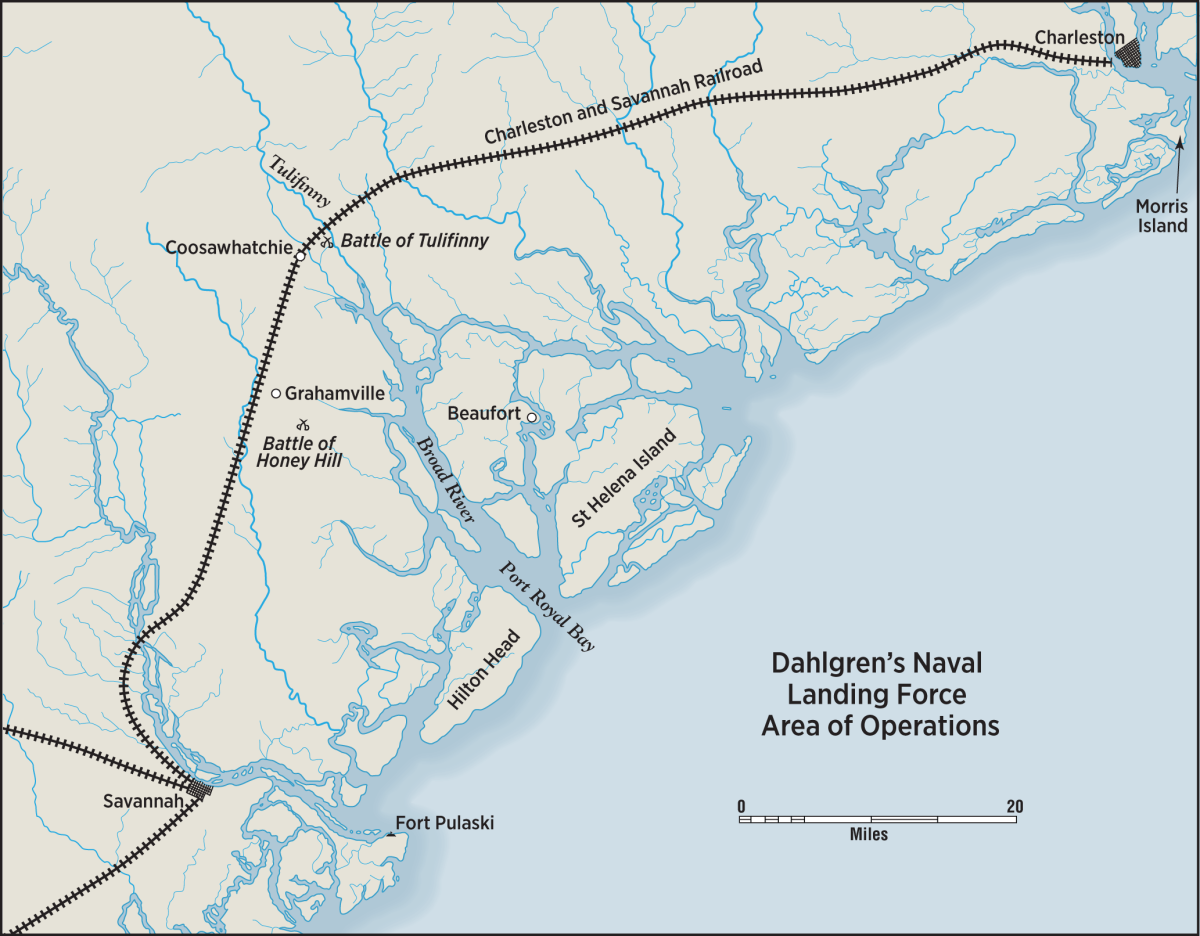

Birth of the Fleet Brigade

On the afternoon of 24 November 1864, the admiral got another chance. Dahlgren received a note from Major General John G. Foster, who commanded the Department of the South, requesting naval cooperation to assist with Major General William T. Sherman’s “March to the Sea.” Days earlier, Sherman’s forces had captured Milledgeville, Georgia, but they were still about 150 miles from Savannah. Envisioned was a diversionary expedition against the Charleston and Savannah Railroad. If Union forces could sever this rail line near Grahamville, South Carolina, they might prevent Rebel reinforcements from reaching Savannah, thus forcing its evacuation. Bringing “all the disposable” troops in his department, General Foster would collect about 5,000 men but would delegate command of the expedition to Brigadier General John P. Hatch. Dahlgren jumped at the opportunity to participate and before he turned in that night issued orders to collect light artillery, sailors, and Marines.7

Dahlgren referred to this force as the Fleet Brigade and detached Commander George Henry Preble to command the unit, which was assembling at Bay Point on South Carolina’s Phillip’s Island. Preble was one of the most senior officers in the Navy, having served more than 29 years. The naval force totaled 493 officers and men. Its 30 officers led three battalions: a naval artillery battalion (140 men), a naval infantry battalion (155), and a Marine battalion (157). Eleven African Americans served as hospital stewards and nurses.8

Dahlgren’s detailed instructions attached 20 men to each boat howitzer—13 to service the gun and another 7 armed with Plymouth rifles to act as infantry support. In addition, four pioneers were assigned to each howitzer to prepare firing positions or construct breastworks. Divided into 50-man companies, the Marines would serve as skirmishers to protect the artillery during engagements and as infantry. Learning from his previous effort, Dahlgren assigned an additional 40 African Americans to perform fatigue duty. Each battalion would have men to cook, pitch tents, etc., freeing the combatants to focus on fighting. To ensure his force could move quickly without a supply train if needed, each seaman in the naval artillery sections carried a round of ammunition. Reserve ammunition would follow in small hand wagons under the fatigue parties. Because the Navy did not have the means to supply horses, forage, and rations ashore, the Army quartermaster fulfilled the Fleet Brigade’s needs in these areas.9

This project had Dahlgren excited as a schoolboy. His flagship, the USS Harvest Moon, picked up Marines from various ships of the squadron. From 26to 28 November, he personally helped organize the seamen and Marines. Dahlgren had his men conduct drills so they would be more certain to act as a disciplined infantry force. Thus, the admiral had them dashing “through the bushes and over sand-hills with howitzers.”10

On the afternoon of the 28th, the men prepared to embark on the expedition. Three sidewheel gunboats arrived to transport the Fleet Brigade. The Pontiac carried the artillery, the Mingoe the naval infantry, and the Sonoma the Marines. Other vessels arrived to transport Hatch’s troops.11

Advance on Grahamville

Dahlgren and Hatch planned to land their force up the Broad River at Boyd’s Landing, 35 miles northeast of Savannah. They would march through Grahamville, a distance of seven miles, and take possession of the railroad just west of there. Fog delayed the expedition for several hours, but the naval contingent began landing at 0900 on the 29th. Within 30 minutes, all of the seamen, guns, and Marines were ashore. Dahlgren landed on the ruins of a wharf, walked a mile with the advance units of his brigade, and remained ashore until 1100. The fog also delayed the Army, and arriving at noon, the troops did not land until that afternoon.12

The Fleet Brigade “pushed to the front” to occupy a crossroad about two miles inland from the landing. The Marines, under the command of First Lieutenant George G. Stoddard, began the march by deploying two companies on each side of the road, with the third in reserve. Following were eight howitzers forming the artillery battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Commander E. Orville Matthews, and the battalion of sailors commanded by Lieutenant James O’Kane. The men halted at a road fork, and Preble deployed the artillery in a defensive position.13

The brigade’s orders were to occupy the point where the Coosawhatchie and Grahamville roads converged. Without a proper map to guide him, Preble was concerned his men might not be at the right crossroad. Taking his adjutant, Lieutenant Commander Alex F. Crossman, and 15 men, Preble reconnoitered two miles in advance of the column. After exchanging shots with Confederate pickets, the scouting party returned, and Preble moved his men, along with an Army regiment that had just arrived, to a crossroad one and a half miles to the north. Union Brigadier General Edward E. Potter rode up later that afternoon and informed Preble that neither of the crossroads he had occupied was the one intended for his men to defend. Once again, Preble moved his “tired and hungry” sailors and Marines. They finally made camp that night at their initial site.14

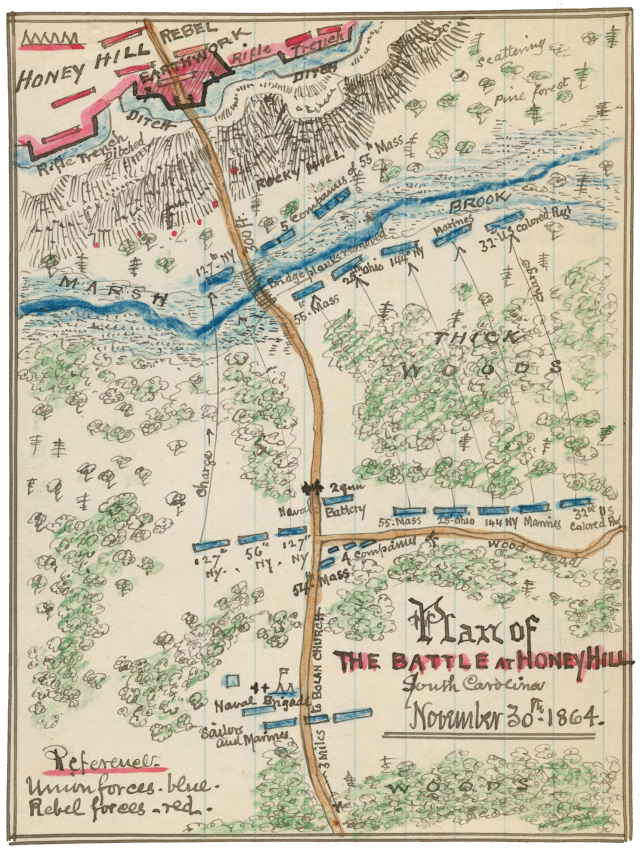

At 0700 on the 30th, Preble had his men moving again, and an hour later he reported to Hatch, who had him send his two lightest howitzers back to the crossroad. Soon after, the Fleet Brigade, along with their remaining howitzers, joined Hatch’s advance toward Grahamville and the railroad. The confused movement of the Union forces allowed the Confederates to assemble a hodgepodge force of about 1,500 men comprising Georgia militia troops, a pair of Georgia infantry regiments, and South Carolina artillery and cavalry units to oppose the Union advance. Before 0930, the Union forces had pushed the Confederates back toward an earthwork on Honey Hill. The Southerners had prepared well by clearing trees and undergrowth in front of the works and situating the defenses between a marsh and dense woods that discouraged attacks from either flank.15

The Rebels easily repulsed two Union Army frontal attacks, inflicting severe losses. At noon, the 25th Ohio Infantry Regiment, supported by the Marine battalion, formed on the right flank for a third assault. After advancing nearly a mile through the woods, the Marines came under heavy artillery fire but continued to engage the enemy until 1500. When the Union Army units began to withdraw a half hour later, the Marines also fell back.16

The Fleet Brigade “behaved splendidly,” reported Preble, but most of it played only a reserve role. The sailors moved two howitzers into line late in the afternoon, firing for about three hours, including discharging the last shots of the battle. One Army officer observed the naval gunners and commented on their enthusiasm. He said it was “laughable” to see them serve the guns with “great dexterity,” firing off a shot and then withdrawing to a nearby ditch. This allowed them to escape the volley of cannon and musket fire that the enemy subjected the pieces to after each discharge. The sailors then “sprang again to their guns.” Thus, they avoided the losses suffered by the Union Army artillery units earlier deployed in the same location.17

The brigade retired in good order and took a position at a crossroad to cover the withdrawal of Hatch’s forces. In the Battle of Honey Hill, Preble’s force suffered trifling casualties of two killed, seven wounded, and one missing. The Union Army suffered just more than 750 killed, wounded, and missing, while Confederates returns reported fewer than 100 casualties.18

Second Attempt at the Railroad

For several days, Union Army units made probing attacks with no clear results. Not satisfied, Dahlgren and Foster agreed to try another advance on the Charleston and Savannah Railroad, near Tulifinny Crossroads. The Fleet Brigade meanwhile remained in a defensive position along the Grahamville Road. The men entrenched and spent time drilling from 1 December until the evening of the 5th. Receiving orders to withdraw, the Fleet Brigade embarked for the expedition up the Tulifinny River and at midnight on 6 December disembarked at Gregory’s Landing, about ten miles northeast of their previous position. The naval infantry landed with Army units and advanced to support troops already ashore. The Marines and guns came ashore at a lower landing. This location proved to be a poor choice because of the marshy terrain. Once landed, the men dragged their howitzers through a swamp with “great labor.”19

Fighting broke out at 0900, and Preble hurried his men toward the sound of musketry. As the main body of the Fleet Brigade reached an open field about two hours later, an enemy cannon began raking its position. With Rebel musket fire also pouring in from nearby woods, Preble wheeled his howitzers into position and, with other Union artillery, drove back the Confederate infantry and silenced their gunfire. The Navy and Marine battalions served as skirmishers on the Union right flank, advanced to near Tulifinny Crossroads, and then moved to a position on the left. This encounter is sometimes referred to as the Battle of Gregory’s Landing.20

The Fleet Brigade slept on the battlefield that night, and soon after daylight on the 7th, Confederates skirmishers renewed the fighting. Preble ordered his howitzers into action and dispersed the skirmishers with artillery and rifle fire. The Confederates then pressed the Union force, and Preble received instructions to leave two heavy howitzers at their present location and to withdraw the rest of his command to the rear and entrench. Amid a hard rain during the latter part of the day and all day on the 8th, the brigade worked to improve its entrenchments.21

On the 9th, the Union leadership opted to clear a road to the railroad to give the artillerists an opening to fire on passing trains. Preble again ordered his men forward on the right. He placed four guns in position to shell the woods in front of a column of advancing Union troops. A Union regiment forged into the woods with axes to clear a 100-foot-wide lane. The Marines, part of the force protecting the axmen, took their position on the extreme right, flanked on the left by two Army regiments. This three-quarter-mile line advanced almost due north under the cover of ten artillery pieces. The Confederates mustered fewer than 1,000 men to oppose the Union advance.

About 350 yards from the railroad, Confederate pickets opened fire on the advancing Yankees. The Union line pushed forward 150 yards, and the Marines, under First Lieutenant Stoddard, made a “gallant attempt” to flank an enemy battery, advancing to within 50 yards of it. Exposed to a “severe fire,” the Union regiment to their left retreated at about the time Stoddard was preparing to charge the battery. Instead, the Confederates advanced and he ordered a withdrawal, with the Marines passing toward the rear alongside the Tulifinny River. The Navy howitzers maintained a continuous fire into the woods on both flanks to discourage any enemy movements that might disrupt the axmen. With the firing lane completed, the Army withdrew without successfully cutting the rail line. During the three days of intermittent fighting, the Fleet Brigade suffered about three dozen casualties while Union Army losses were about 200; Confederate casualties were 52.22

Ideas to Build On

Dahlgren was proud of the actions of the Fleet Brigade. He authorized distinguishing pennants for each battalion—red for the naval artillerists, blue for the naval battalion, and white and blue for the Marines—all marked with an anchor. On 20 December, Confederate troops evacuated Savannah, which was occupied by Sherman’s troops the next day. Dahlgren disbanded his brigade on 5 January, and the men returned to their ships.23

Union attempts to cut the Charleston and Savannah Railroad had little impact on the war effort. Had either probe succeeded, it would have materially helped Sherman’s campaign. The Marines and sailors behaved well under fire and fought as a disciplined and effective force. Hatch held the Fleet Brigade in high esteem, commending their “gallantry and action and good conduct during the irksome life in camp.” He believed any “jealousy” that existed between the service branches disappeared after they fought in harmony.24

The Honey Hill and Tulifinny engagements were not a sufficient test for Dahlgren’s concept of a naval landing force. His ideas, however, were models for later amphibious operations. Dahlgren’s Fleet Brigade exhibited many of the components of a modern Marine Corps expeditionary force. It had specialized equipment and designated logistical elements. It participated in an expeditionary warfare mission to seize the Charleston and Savannah Railroad, part of a task-oriented force closely integrated with Army units. The brigade was forward deployed and had sustainable power projection. This matches the doctrine in the Department of Defense’s Joint Doctrine for Amphibious Operations, Joint Publication 3-02.25

While Dahlgren’s ideas were more simplistic than the tenets of current amphibious doctrine, advanced modern technology thoroughly has shaped the contemporary principles of amphibious warfare. Dahlgren’s foresight is worth taking into account when considering John Lejeune as the visionary of amphibious warfare. But while Dahlgren’s concepts predate some of Lejeune’s by decades, the admiral can never take Lejeune’s place as the father of the modern Marine Corps.

1. Robert H. Rankin, Small Arms of the Sea Services (New Milford, CT: N. Flayderman and Co., 1972), 118; John A. Dahlgren, Boat Artillery and Infantry, 8 August 1864, Orders to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, 1863–1865, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (hereafter HSP).

2. CAPT John A. Dahlgren, USN, “Form of Exercise and Manoeuver for the Boat-Howitzers of the U.S. Navy” (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1862); Preble to Dahlgren, 5 December 1864, Richard Rush et. al., Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894–1927), ser. 1, vol. 16, 78 (hereafter ORN).

3. Madeleine Dahlgren, Memoirs of John A. Dahlgren Rear Admiral United States Navy (Boston: J. R. Osgood, 1882), entries for 12 July, 8 August 1863, 400, 406; Dahlgren to Parker, 12 July 1863, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 14, 337; Dahlgren to Welles, 29 June 1863, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 14, 303; Welles to Dahlgren, 3 July 1863, Dahlgren Papers, Library of Congress Manuscripts (hereafter cited as LCM); Dahlgren to Welles, 6 August 1863, LCM, 428.

4. Dahlgren Instructions, 7 August 1863, LCM, 428–29; Zeilin to Dahlgren, 10 August 1863, LCM, 434.

5. Zeilin to Dahlgren, 13 August 1863, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 14, 439–40; Dahlgren, Memoirs, 14 August 1863, 407.

6. Dahlgren to Welles, 15 June 1865, Dahlgren Papers, LCM.

7. Dahlgren, Memoirs, 24 November 1864, 477–78, 608; Foster to Halleck, 7 December 1864, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office), ser. 1, vol. 44, 420 (hereafter ORA); Hatch to Burger, December (nd) 1864, ibid., 421–22.

8. Preble to Hatch, 2 December 1864, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 74.

9. Dahlgren to Preble, 26 November 1864, ORN, 66–67; Hatch to Preble, 4 October 1866, Preble Journal, Operations of the Fleet Brigade, Subject File HJ, Joint Military-Naval Engagements, Record Group 45, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington DC (hereafter NARA); General Instructions, John A. Dahlgren, 26 November 1864, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 67–68; William A. Courtney, “Fragments of War History Relating to the Coast Defense of South Carolina 1861–65 and the Hasty Preparations for the Battle of Honey Hill, November 30, 1864,” Southern Historical Society Papers 69 (1898); John A. Dahlgren, Dahlgren Biography, 229, John A. Dahlgren Papers, Navy Department Library, Washington, DC; Dahlgren to Reynolds, 25 November, 1864, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 63; Entry for 28 November 1864, George H. Preble Diary, George H. Preble Papers, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA (hereafter AAS).

10. Dahlgren took all the Marines off the blockaders along the southeastern coast. Green to Patterson, 25 November 1864, Green Journals, Port Columbus; Dahlgren, Memoirs, 25–28 November 1864, 478; Dahlgren to Reynolds, 25 November 1864, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 63.

11. Dahlgren to Preble, 28 November 1864, ORN, 69; Dahlgren to Welles, 26 November 1864, ORN, 65.

12. Dahlgren Order No. 101, 28 November 1864, Orders to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, 1863–1865, HSP; Dahlgren, Memoirs, 28 November 1864, 479–80; Dahlgren to Welles, 30 November 1864, Dahlgren Papers, LCM; Dahlgren to Balch, 29 November 1864, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 71; Hatch to Burger, December (nd) 1864, ORA, ser. 1, vol. 44, 421–22.

13. Preble to Hatch, 4 December 1864, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 76; Stoddard to Zeilin, 5 January 1864, ORN, 63.

14. Charles Soule, “The Battle of Honey Hill,” Peter Cozzens and Robert Girardi (eds.), The New Annals of the Civil War (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2004), 449. Potter was also confused; he took the wrong road and marched his men six miles before returning. Preble to Hatch, 4 December 1864, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 76; Preble to Dahlgren, 5 December 1864, ORN, 78–81; Hatch to Burger, December (nd) 1864, ORA, ser. 1, vol. 44, 422–25.

15. Smith to Hardee, 6 December 1864, ORA, ser. 1, vol. 44, 415–16.

16. Preble to Dahlgren, 5 December 1864, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 78–81; Smith to Hardee, 6 December 1864, ORA, ser. 1, vol. 44, 415–16.

17. Entry for 4 December 1864, Preble Diary, Preble Papers, AAS; Soule, “The Battle of Honey Hill,” 463.

18. Confederate casualties were probably higher because several units made no reports. Dahlgren to Welles, 1 January 1865, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 96.

19. Preble to Dahlgren, 7 December 1864, Dahlgren Papers, LCM; Preble to Dahlgren, 8 December 1864, 10 January 1865, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 84–87, 105–6.

20.Stoddard to Zeilin, 5 January 1864, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 100.

21. Preble to Dahlgren, 10 January 1865, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 107–8; Dahlgren to Welles, 1 January 1865, ibid., 97; Entry for 7 December 1864, Preble Diary, AAS.

22. Preble to Dahlgren, 10 January 1865, ORN, ser. 1, vol. 16, 107–9; Stoddard to Zeilin, 5 January 1864, ORN, 101; Woodford to Perry, 15 December 1864, ORA, ser. 1, vol. 44, 441.

23.Dahlgren to Preble, 9 December 1864, ORN, 1, vol. 16, 88.

24. Hatch to Dahlgren, 7 February 1865, Dahlgren Papers, LCM.

25. Department of Defense, Joint Staff. Joint Publication 3-02, Joint Doctrine for Amphibious Operations, Washington, DC, 2001.