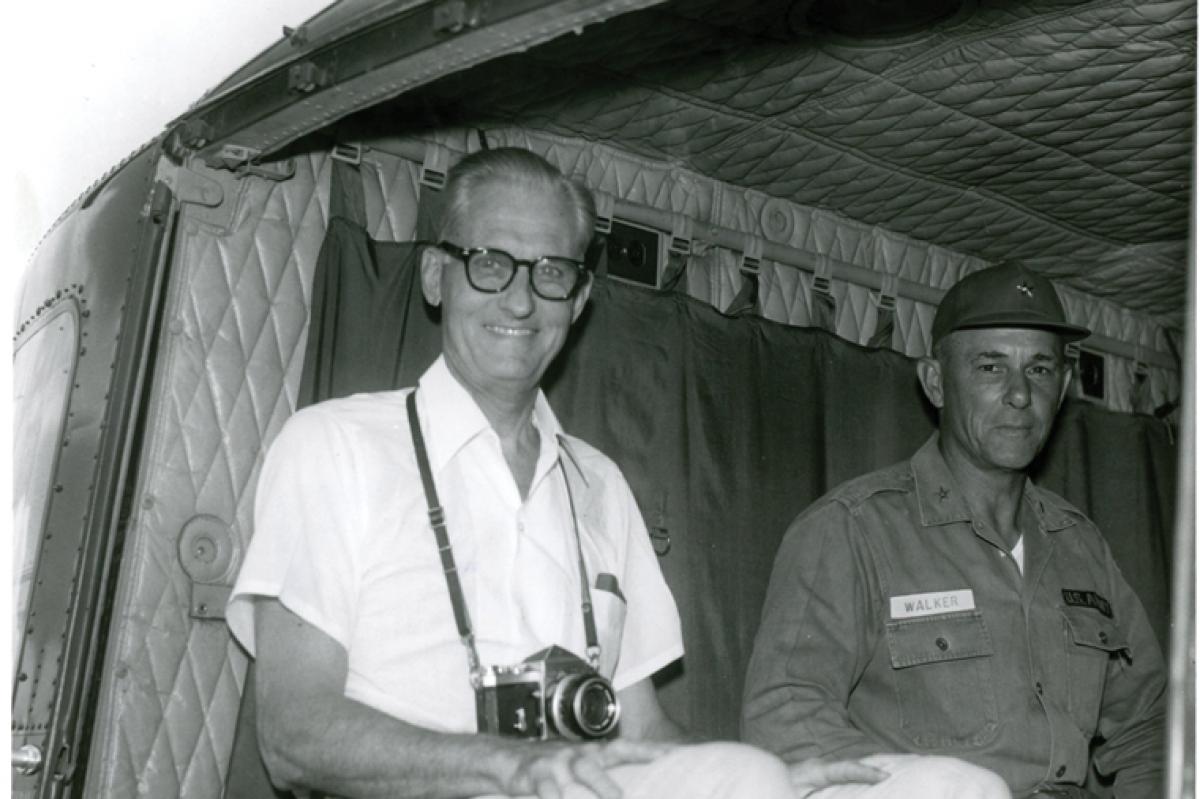

Baldwin, for many years the military editor of The New York Times, earned a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the early phase of World War II. In his U.S. Naval Institute oral history, conducted in 1976, Baldwin offered insightful perspective on American ambivalence over getting entangled in the conflict—and described his personal reservations at the outset regarding the amount of aid and material the United States was supplying to Britain.

There was one period where I found myself considerably at odds with some of our policies. Remember, before we got into the war the British were trying to order more and more arms and planes from the United States, and the policy of the administration was to let them have this, even at our own expense. I didn’t think that was too good an idea, particularly in view of the situation that then existed in England, and I wrote one or two pieces which showed that we were stripping some of our operating forces in order to send material overseas. I wrote quite a few factual pieces describing what war reserves we had and what was happening to them. We gave a tremendous amount to Britain in that summer of 1940—that year of 1940–41.

Then we started turning over B-24s, of which we had very few. Our Air Corps was quite concerned about this, and the British were pressing us hard to get them. I remember writing one piece that elicited a response from Commander, Coastal Command, Royal Air Force, Air Marshal [John] Slessor. He wrote a letter to me, I think, and also made some sort of a public statement. I think he was on a purchasing mission to the United States, and he stressed the importance of these planes to Britain. I still wasn’t convinced, but Roosevelt continued to give them the planes.

I thought it was completely uncertain at that time that Britain could hold out, and I still think in retrospect that if the Germans had been determined to gain local air superiority over the southeast of England and had confined it to that, that they could have made a successful landing. I think they dispersed their efforts so much and shifted from one objective to another that they couldn’t succeed. Hitler’s heart was never really in the invasion. It was improvised, as we know now, and impromptu. But we didn’t know that then, and neither did the British.

I had the feeling that we were in a situation where we ought to consider our own interests first and foremost, that this was a world of complete change. Don’t misunderstand me. I wasn’t an isolationist, but I felt very strongly that we had to be able to defend ourselves in the Western Hemisphere. By that I included South America and Greenland, and we didn’t have anywhere near enough to do it. Then, after the invasion of Russia, I felt very strongly that we would be intervening on the side of one or the other of the tyrannies, and that they’d probably end up with one or the other supreme (as indeed happened) instead of letting them exhaust each other. There was no reason to expend good American blood for that purpose.

Also, the shipbuilding program at this time was creating bottlenecks in all the American shipyards. There weren’t enough skilled people to go around, and we were trying to build for Britain as well as ourselves. Logjams were developing everywhere.

I seem to remember that there was the question of industrial mobilization in Washington. Bernard Baruch [adviser to the Office of War Mobilization] was very strongly on one side. His old mobilization plan was based upon a concept that was somewhat out of date. But he was fighting a vigorous battle to get this enacted, to get Roosevelt to carry it out exactly. Every once in a while, Baruch would call me up after I had an article on the subject and either object to or appraise the article in question.

Mobilization in Washington came to be such a political exercise that it didn’t necessarily follow a logical or rational pattern. The scope of what I was writing about grew broader and broader, because I discovered, as I think the Times did and nearly everyone else, that modern war meant everything. It dawned on me gradually that this was the meaning of total war. It was everything—psychology, and everything else.