Gideon Welles was an important political figure in Connecticut, serving as postmaster of Hartford and editor of the Hartford Times and Hartford Evening Press. But President Abraham Lincoln appointed him Secretary of the Navy primarily because of political geography. In those days it was considered essential that each region of the country be represented in the Cabinet, and Lincoln selected Welles as the New England representative over Nathaniel P. Banks of Massachusetts, who was the other contender. As a consolation prize, Banks was appointed a major general, though he subsequently proved to be a very disappointing one.

Welles’ appointment was not universally popular. When the New York political operative Thurlow Weed learned of it, he told the President that if he really wanted “an attractive figure-head, to be adorned with an elaborate wig and luxuriant whiskers,” he could easily “transfer it from the prow of a ship to the entrance of the Navy Department” and it would prove “quite as serviceable” as Welles. Lincoln deflected the mean-spirited taunt by replying, “Oh, wooden midshipmen answer very well in novels, but we must have a live secretary of the navy.” Similarly, when the 40-year Navy veteran Captain Samuel Francis Du Pont learned of Welles’ appointment, he wrote to a fellow officer that the best thing he could say about the new Secretary was that when Welles had served as the chief of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing, he had “made a remarkable contract for cheese.”1

Over the years, those kinds of flippant assessments have encouraged historians to dismiss Welles as a cartoonish character—a voluble, sputtering, quick-tempered arriviste who was little more than a figurehead at the Navy Department, where the important decisions were supposedly made by the assistant secretary, former naval officer Gustavus V. Fox. Such a conclusion is both misleading and unfair to Welles. In fact, he was earnest, candid, hard-working, loyal, and remarkably successful in managing the greatest naval expansion in the nation’s history until World War II. In testimony to that, Welles was one of only two men, Secretary of State William H. Seward being the other, to hold his Cabinet position throughout Lincoln’s presidency and into the Johnson administration.

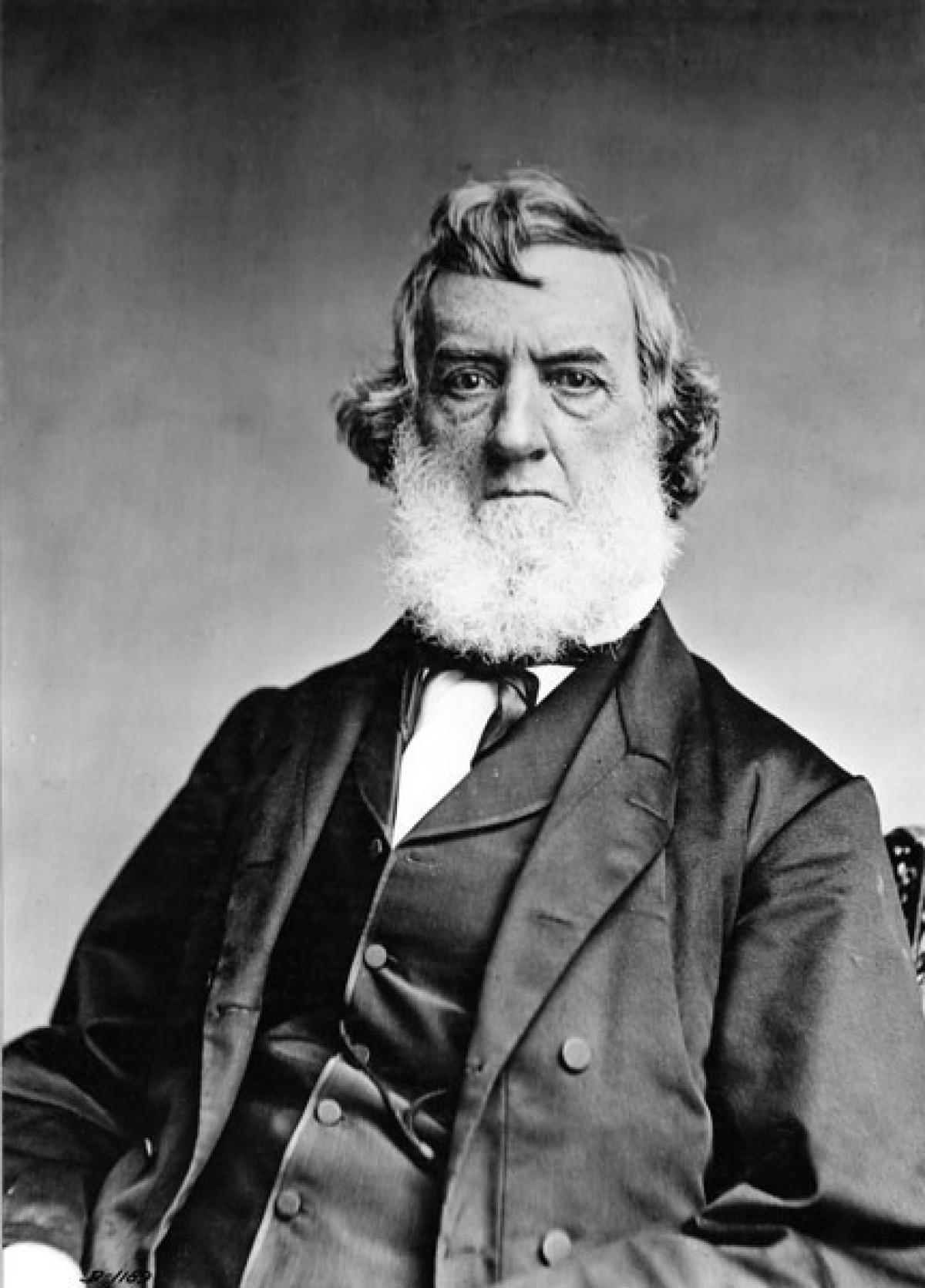

The origins of the negative appraisals of Welles’ tenure as Navy Secretary are easy to identify. For one thing, he looked eccentric. As Weed noted, he had “luxuriant whiskers”—a full, bushy white beard that no doubt contributed to Lincoln’s nickname for him, “Father Neptune,” and he wore an elaborate shoulder-length wig. Welles had purchased it some years earlier when he first began to lose his hair. At that time his beard was still brown and only slightly tinged with gray, and he bought a wig to match. When his whiskers turned to white, his Yankee thrift apparently prevented him from buying a new wig, so that by the time he became Secretary of the Navy, the difference between the lustrous brown hair and snow white beard was jarring. Moreover, when at his desk, Welles had a tendency to push the wig back on his head as he worked, and on other occasions it rested crookedly on his head, which gave him a comical look. Those who found Welles too blunt or insufficiently cooperative seized on such details to portray him as a clown.

In addition, Welles not only spoke his mind freely, he did so without much regard for the popular view of the day or the personal feelings of others. There was little nuance in Welles’ worldview: On most issues he saw things as either manifestly right or utterly wrong, and he did not spare those who either were wrong (in his view) or attempted to temporize. He found the dithering Major General Henry W. Halleck and the hesitant Major General George B. McClellan contemptible, and he said so. His judgmental attitude earned him many enemies, but it also won him the gratitude of the President, who appreciated Welles’ candor and counted on his Secretary of the Navy to be honest and straightforward, even if Lincoln did not always accept his views.

For both his eccentricity and his candor, Welles was often a target of opposition newspapers. During the Civil War, newspapers made no pretense of being neutral reporters of events, and instead openly championed one political party or the other. In New York City the Democratic paper was the New York Herald. Editor James Gordon Bennett routinely attacked the Lincoln administration on the grounds of perceived inefficiencies, particularly targeting Welles’ Navy Department. Every time a Rebel ship made it through the blockade or a Confederate commerce raider seized a Union merchantman, Bennett trumpeted it as another failure of Welles’ Navy Department. During the rampage by the CSS Alabama in 1863, Bennett wrote that her success as a commerce raider was evidence of “the neglect, the carelessness, the incompetency, and the utter imbecility of the Navy Department.” By humiliating Welles, Bennett hoped to embarrass the Lincoln administration and promote the interests of New York Democrats.2

All those circumstances contributed to a historical view of Gideon Welles that emphasizes his eccentricity and undervalues his contributions to victory, even though those contributions were many and substantive. Despite unprecedented difficulties, Welles played a central, even a crucial, role in virtually every aspect of the naval war. He supervised the expansion of the Navy from 42 warships in 1861 to 671 ships by 1865; he authorized and organized the strategic planning for the deployment of that armada; he was an early and consistent advocate of innovation, especially the acquisition of armored warships; and he oversaw the promotion (and dismissal) of key Navy leaders. In each of these roles he remained his uncompromising, blunt self and was consequently a target for critics, but in each case he faced down the criticism and emerged justified.

Welles’ first great task was to enlarge the Navy. Despite the two dozen steam warships that had been built in the last decade before the war, Lincoln’s blockade declaration on 19 April 1861 meant that the prewar Navy would have to be hugely expanded. To accomplish that, Welles immediately did three things: order home all the ships on distant station patrol; authorize the construction of 23 new steam warships (the original 90-day wonders), doing so without congressional approval in the hope that Congress would approve his decision after the fact, which it did; and begin a program to purchase merchant ships and convert them into men-of-war. The latter proved, by far, to be the Union Navy’s most prolific source of new warships, and in the end, 418 of the Navy’s 671 combatants were converted merchantmen.

The man Welles selected as the Navy’s purchasing agent for the ships was his brother-in-law George D. Morgan, who had carte blanche to buy whatever vessels he believed suitable, and to pocket generally a 2½-percent commission for every ship he bought. Naturally, the arrangement provoked sharp criticism about nepotism and peculation in the opposition newspapers, especially Bennett’s New York Herald. The chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, John P. Hale, insisted it was simple graft and corruption, and announced congressional hearings.

Hale’s motive was political: He was angered that Welles had not granted enough government contracts to Hale’s friends and political allies, and he hoped to secure Welles’ dismissal. His plan was derailed when he could not turn up any actual examples of fraud or corruption. Morgan bought some 89 ships for the government at a cost of $3.5 million, a bargain at an average of $40,000 per vessel. Morgan thereby earned commissions of some $70,000, a huge sum in 1861. Embarrassed by that and by the public outcry, Morgan offered to return all the money, but Welles would not hear of it. Characteristically, his view was that a contract was a contract and Morgan was entitled to every penny.3

Welles also established the first naval strategy board in American history. Aware that establishing a blockade meant more than simply sending warships one at a time down to anchor off one or another Southern harbor, the Navy Secretary called together a panel of experts headed by Captain Du Pont, with instructions to establish organizing principles for the blockade and the management of the saltwater war. The report of the committee led to the creation of the four blockading squadrons; the seizure of Port Royal, South Carolina, in November 1861; and eventually the establishment of a Union foothold all along the Rebel coast.4

Welles actively promoted the Navy’s first ironclads. Only a few months into the war, it had become evident that the Confederates in Norfolk were converting the former U.S. steam frigate Merrimack into an iron-armored battery. Though veteran officers tended to be skeptical of the dangers posed by such a warship, Welles decided it was essential to develop a counterweapon. He asked Congress for an appropriation of $1.5 million for the construction of three experimental ironclad warships, and issued a call for proposals. By the end of the summer, a score of designs had been submitted to the Ironclad Board, composed of three officers. The officers themselves, all very senior Navy captains, tended to favor the proposals that looked most like the ships they already knew and understood. But with Lincoln’s support, Welles ensured that one of the designs selected was John Ericsson’s for the vessel that eventually became the Monitor.

After the Monitor’s success against the Virginia in Hampton Roads on 9 March 1862, Welles became an enthusiastic champion of ironclads, and especially ironclads of the Monitor type, characterized by a rotating turret. Indeed, Welles’ commitment to those ugly ducklings of the naval war very likely led the Union to overlook alternate designs that might have proved equally successful or even better. That blind spot led him to reject the assessment of Du Pont, then commanding the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, that “monitors” were not a kind of magic bullet that would allow him to steam triumphantly into Charleston Harbor and put the city under his guns.

Thanks to Welles, we know as much as we do about the inner workings of the Lincoln Cabinet. Throughout his years as head of the Navy Department, he kept a careful record of each day’s events. He was even more candid in his private diary than he was in his public conversation, and since the publication of the diary 50 years ago, it has provided historians with a rich supply of insider observations about Lincoln, his Cabinet, and the generals and admirals who ran the war. Welles did not suffer fools of any rank, and he wrote scathingly about his Cabinet rivals (especially Secretary of State Seward and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton), Army generals (especially Halleck and McClellan), and, of course, the senior officers of the Navy.

He did not, however, criticize Lincoln, whose only weakness, Welles believed, was that he was too tenderhearted to protect himself from the many charlatans who tried to take advantage of his generosity and compassion. Welles cast himself in the role of Lincoln’s protector against such “schemers,” a group that, in Welles’ view, included both Seward and Stanton. Of the former, Welles wrote that the Secretary of State was “assuming, presuming, meddlesome, and uncertain,” that he had “no great original conceptions of right, nor systematic ideas of administration,” and that he was “a trickster” who sought to take advantage of Lincoln’s “wonderful kindness of heart.”5

For all his eccentricities, including his mismatched wig, blunt and judgmental assertions, and unapologetic standard for promotion and recognition, Welles proved to be a responsible and reliable administrator whose contributions to Union victory are often underappreciated.

1. Thurlow Weed, The Life of Thurlow Weed (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1883), vol. 1, p. 611; Du Pont to Samuel Mercer, 13 March 1861, in Samuel Francis Du Pont: A Selection from his Civil War Letters, edited by John D. Hayes (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1969), vol. 1, pp. 42–43. The best biography of Welles is John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973).

2. The New York Herald, 9 October 1863.

3. Craig L. Symonds, Lincoln and his Admirals (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 57–59; Craig L. Symonds, The Civil War at Sea (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2009), p. 35.

4. Kevin Weddle, Lincoln’s Tragic Admiral: the Life of Samuel Francis Du Pont (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2005), pp. 106–24; Stephen R. Taaffe, Commanding Lincoln’s Navy: Union Naval Leadership during the Civil War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2009), pp. 225–29.

5. Gideon Welles, The Diary of Gideon Welles, ed. by Howard K. Beale (New York: W. W. Norton, 1960), entry of 16 September 1863, vol. 1, pp. 134–35. See also Gideon Welles, Lincoln and Seward (New York: Sheldon, 1874).