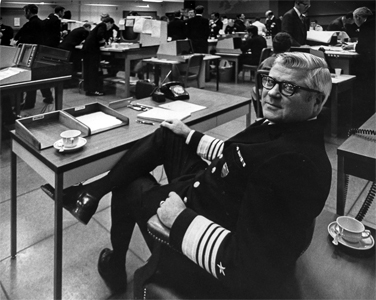

Train, Harry DePue II, Adm., USN (Ret.)

(1927–)

Because he grew up in a Navy family, Train was imbued from childhood with the goal of attending the Naval Academy. His career as a midshipman included playing center on the football team that played to a notable tie against West Point in 1948. After graduation in 1949, Train served as a junior officer in the destroyer USS Harold J. Ellison (DD-864) in the Atlantic and Mediterranean and in the destroyer USS Harry E. Hubbard (DD-748), which was reactivated for Korean War service. After submarine school in 1951, Train served in the submarine USS Wahoo (SS-565), whose skippers, Dennis Wilkinson and Bill Anderson, both later commanded the USS Nautilus (SSN-571). After duty in 1957-58 on the Joint Staff, Train was executive officer of the submarine USS Entemedor (SS-340) and submarine placement officer in the Bureau of Naval Personnel. In 1962-64, after resisting Admiral Hyman G. Rickover's efforts to draft him into the nuclear program, he was commanding officer of the diesel submarine USS Barbel (SS-580). After that he was administrative aide to Secretary of the Navy Paul Nitze and developed a close working relationship with Nitze's EA, Elmo Zumwalt. Subsequently, Train commanded the guided missile destroyer USS Conyngham (DDG-17) in the Med, served briefly on the Second Fleet staff, and then was executive assistant to Admiral Thomas Moorer during Moorer's duty as CNO and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. As a flag officer, Train commanded Cruiser-Destroyer Flotilla Eight, headed the systems analysis division of OpNav, and was involved in Incidents at Sea negotiations with the Soviet Union. After service in 1974-76 as director of the Joint Staff, he spent two years as Commander Sixth Fleet, and then served from 1978 to 1982 as Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic; Commander in Chief, Atlantic Command; and Commander in Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet. Admiral Train's oral history also includes his analysis of the 1982 Falklands War and discussion of his activities following retirement from the Navy, from hiking the Appalachian Trail to running his own defense consulting firm to serving in a variety of nonprofit pursuits.

Interview

In this selection from his second interview at his office at Strategic Research and Management Services Inc. in Norfolk, Virginia, on 16 July 1986, Admiral Train reflects on the psychic rewards of command at sea as CO of the USS Barbel (SS-580).

Admiral Train: The boat operated like a Swiss watch. It went fast. Each of those three submarines in the Barbelclass had some differing characteristics. We had clam-shell doors on the top of the sail, just like modern nuclear submarines do. They gave you a completely flat fairing on top of the sail when the periscopes and the masts were down. The other submarines didn't have clam shells. We also did not have the things that turned out to be a problem on the other boats. They called them rat traps. These were doors on the fairings for the ballast tanks that would have enabled you to close off and fair the ballast tanks. Even nuclear submarines today don't have those. They didn't work very well, and we were blessed by not having them.

We were about four knots faster than the other two submarines in the class, for reasons no one has ever adequately explained. The Barbel handled like a dream. We were still in the process of learning how to handle that hull shape, and we were, as a crew, virtually in the position of being test pilots for that hull form.[1] In very high-speed operations, it would do things that all your previous submarine experience didn't condition you for. One of the tendencies that it had was at very high speeds, when you put the rudder on, instead of the bow coming up, the bow would go down. Well, that's common knowledge in submarines today, that at high speed the bow does something different than it does at low speed.

We had Admiral Chick Clarey, who was then the submarine force commander, out with a bunch of SecNav guests.[2] He asked us to do what they call hydrobatics, very high-speed maneuvering. We were doing 23 knots and changing depths and making course changes. The boat would roll 37 degrees, what is called snap roll at a max-speed, max-rudder turn. On one occasion we were turning and changing depth at the same time. The bow went down instead of up, and all the inclinometers and the gauges went off the scale, so I have no idea of what angle we achieved, but somewhere in excess of a 50-degree down angle. The more the planesman pulled back on the yoke, to put more stern planes on it, the tighter the turn became, the more the roll. We were in what the aviators call a graveyard spiral. The stern planes became the rudder and we were turning tighter, and the rudder became the stern planes.

That right rudder was driving us down, and we didn't know what to do. So we took all the rudder off and the boat pulled itself out. It was a very stable boat. As soon as we let go of the rudder, it pulled itself out. But our vertical component was in excess of 1,000 feet a minute down. We didn't have much time to pull out.

Paul Stillwell: That must have been a startling sensation for Admiral Clarey.

Admiral Train: Yes, he was a little wild-eyed after it was all over. [Laughter]

Paul Stillwell: What were the psychic rewards of being a commanding officer?

Admiral Train: Accountability. I mean, you can almost wallow in accountability, knowing that there's no one else to turn to, that you're the ultimately accountable authority. No matter how much you delegate authority and chores to people, ultimately you're accountable. And I found that a very comfortable role to be in. No one was looking past you; they were just looking at you. It's hard to explain, but it's very satisfying.

Command at sea really defies description. You can write about it all you want, but it means different things to different people. To some it means importance, and the authority is more important than the accountability. To others it means loneliness. I never found it to be a lonely role, but other commanding officers that I've known very closely, because of that role and because they are constantly contemplating their role, sort of detached themselves mentally and emotionally from the people around them.

[1] The Barbel was one of the early submarines with a tear-drop shaped hull of the type proved in the USS Albacore (AGSS-569). The hull form was designed to facilitate operation underwater, whereas previous submarines were designed essentially as submersible surface ships.

[2] Rear Admiral Bernard A. Clarey, USN, served as Commander Submarine Force Pacific Fleet from 1962 to 1964. He was later a four-star admiral and Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet. His oral history is in the Naval Institute collection. SecNav—Secretary of the Navy.

Interview (Cont'd)

This selection is from Admiral Train's fourth interview with Paul Stillwell at his office in the Science Applications International Corporation in Norfolk, Viriginia, on Wednesday, 17 July 1996. Because it is a continuation of thoughts from the previous day's interview, it's content has been grouped with the third interview in the printed version. In the selection, Train recalls the Son Tay POW raid from his then-vantage point as assistant to the Chairman of the Join Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Thomas Moorer, USN.

Admiral Train : In connection with Vietnam, I thought that the Son Tay prison raid was one of the more interesting events that occurred during the time that I was executive assistant to the Chairman.[1] It was a very, very highly classified planning evolution and very highly classified operation. The operational commander in the field was an Army colonel named Bull Simons, a special forces guy.[2] The overall commander in the field was an Air Force brigadier general named Roy Manor.[3]

The operation was planned using very, very few people. There was, at that time, a special forces director on the Joint Staff, General Blackburn, who headed up the planning effort.[4] Roy Manor and Bull Simons also fully participated in not only the training and execution but also the planning. Bull Simons made quite a few visits to Admiral Moorer in his office, which is a very unusual way for the Chairman to oversee the planning, training, and conduct of an operation.

We decided that we really did know where a large group of prisoners were. We planned a raid to go in and take those prisoners out. But in order to train for that raid, we had to assemble a force and build a full-size replica of the prison camp down at Eglin Air Force Base.[5] We erected it at night and collapsed it during the daytime so that the Soviets couldn't see it from their satellites. The rescue force trained for the better part of a month to go in and conduct the raid.

The raid was to be conducted using an H-3 helicopter, which is a very slow helicopter, to actually land inside the prison compound.[6] Then there would be support from H-53 helicopters that would land outside.[7] The rotor blade clearance for this landing inside the compound was about two feet on each side, so it was a very, very tight operation. They completed their training, and then we deployed them under the command of Roy Manor, who was Air Force Special Forces, to Vietnam and then waited for the appropriate time to conduct the raid.

When the raid was conducted, it was monitored by the JCS in the JCS conference room by radio. The night before the raid, the Secretary of Defense approved the execution of the raid and gave us a specific date. The night before, Mr. John Hughes, from the Defense Intelligence Agency, came in to see Admiral Moorer. He had been the photo interpreter who detected the missiles in Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis and was then the deputy director of DIA.

I was present at this meeting when Hughes told the admiral that the prisoners weren't there. Admiral Moorer quizzed him about how he knew that the prisoners weren't there. He said the photos showed the grass hadn't been walked on in a week or two, and that would indicate to him that the prisoners weren't there. The only other explanation was that they had all the prisoners locked inside and weren't letting them out to exercise.

So Admiral Moorer and I went up to see Secretary Laird, and Admiral Moorer recommended that we cancel the operation. Secretary Laird said that he didn't believe there was any way we could cancel the operation. One, he didn't have 100% confidence that John Hughes's interpretation was correct. The nation would never forgive us if we went through all that training, canceled the operation, and then found out that the prisoners were, indeed, still there. Second, having gotten this far, there was surely going to be a leak somewhere that we had planned and then canceled this operation, and he did not think that would be politically helpful to the President.

So we went ahead and executed the operation, knowing—at some high confidence level—that the prisoners were not there.

Paul Stillwell: As indeed they were not.

Admiral Train: As indeed they were not.

[1] On 20 November 1970 a U.S. commando force landed at the Son Tay prison, 23 miles west of Hanoi, North Vietnam, in an attempt to free U.S. prisoners of war reported to be held there. The commandos did not recover any POWs, because they had been moved to another location shortly before.

[2] Colonel Arthur D. Simons, USA.

[3] Brigadier General Leroy J. Manor, USAF.

[4] Brigadier General Donald D. Blackburn, USA, Special Assistant for Counterinsurgency and Special Activities to the Chairman of the JCS.

[5] Eglin Air Force Base is near the towns of Valparaiso and Niceville in the panhandle region of western Florida.

[6] The SH-3 Sea King, primarily an antisubmarine helicopter, had a maximum speed of approximately 165 miles per hour.

[7] The CH-53 Sea Stallion was a troop-carrying helicopter operated by the Marine Corps. It could accommodate 55 troops and had a cruising speed of 173 miles per hour.

About this Volume

Based on seven interviews conducted by Paul Stillwell from July 1986 to October 1996, the volume contains 534 pages of interview transcript plus a comprehensive index. The transcript is copyright 1997 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee has placed no restrictions on its use.