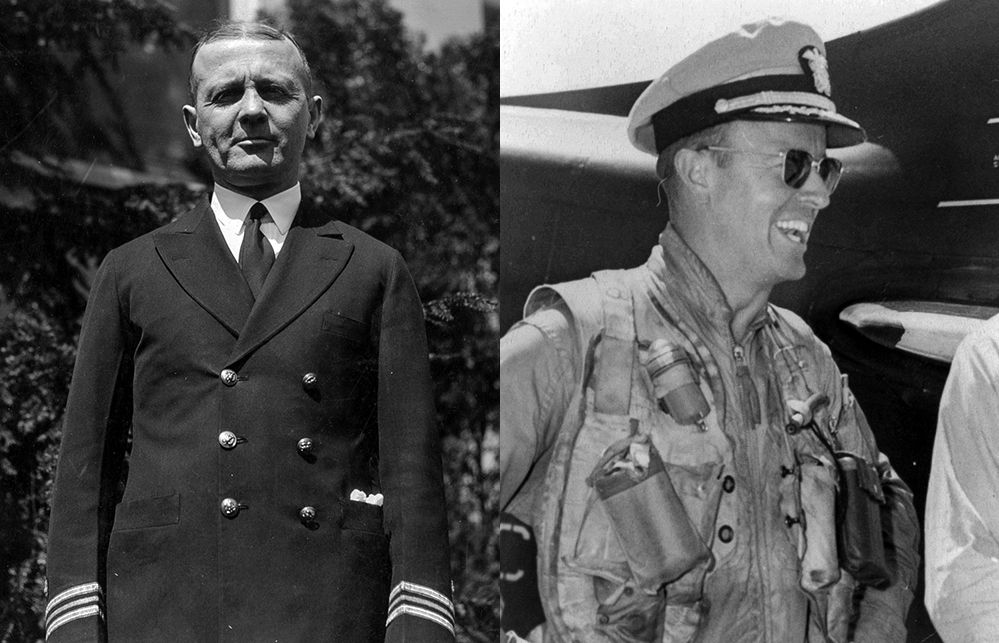

Melhorn, Kent C., Rear Adm., MC, USN (Ret.) and Cdr. Charles M. Melhorn, USN (Ret.)

(1883–1978; 1918–1983)

This volume comprises one interview each with a Navy father and a Navy son. The father was a doctor who served on active duty from 1907 through 1946. He had a variety of duties both at sea and ashore, and he describes them in a fascinating manner: with the Marines in Santo Domingo in 1915, two tours as a public health official in Haiti in the 1920s, two tours on the staff of Commander in Chief U.S. Fleet, and a stint as attending physician to the U.S. delegation to the World Disarmament Conference at Geneva in 1932. During World War II, Admiral Melhorn commanded the Navy Medical Supply Depot in Brooklyn.

Commander Melhorn led a charmed life from the time of his enlistment in the V-7 program in 1940 until his retirement in 1961. His PT boat was blown up at Guadalcanal in 1942; he then survived a plane crash during flight training, a midair collision, attacks on the Japanese fleet in 1945, a tour on Rear Admiral Jocko Clark's Carrier Division Four staff in 1949-1950, and a night ditching at sea in the Mediterranean in the 1950's. Through all of that, he managed to retain the delightful sense of humor which is evident in his oral history.

Interview I

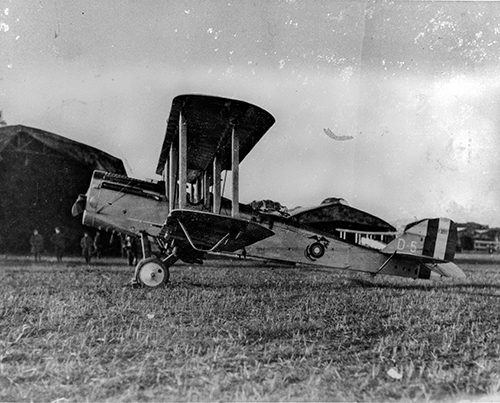

In this clip from his 14 February 1970 interview with Commander Etta-Belle Kitchen, USN (Ret.) and his son, Commander Charles M. Melhorn, USN (Ret.), Admiral Melhorn speaks of his deployment to Haiti in the early 1920s and his surviving a crash of a Marine DH-4B fighter plane in 1921.

Admiral Melhorn: While on duty in Port-au-Prince at the Haitian General Hospital, I received a telephone call one day from a fellow medical officer on the south coast of Haiti, a town called Jacmel, that one of his children was seriously ill and he asked for help; so I volunteered to go. It would mean an eight-hour ride on horseback or a half an hour ride in a plane.

So I asked for a plane from the Marines, and they gave it to me. All their regular pilots were off on duty somewhere, so they gave me a sergeant in the Marines, who was experienced, but not quite as well as a number one pilot. We flew over the mountains, about 6,000 feet maybe.

Commander Melhorn: What were you in?

Admiral Melhorn: We called them the Jenny, another name was "flying coffin." There was no air field in Jacmel but a fairly good beach. So we landed on the beach, but we wound up on the nose of the plane. We'd hit a big cactus bush on the beach. Nobody was hurt; the pilot got out and he said he thought it was all right. I went about my business up the hill and did what I could to take care of the child, and when I came back, he assured me that everything was all right, so we took off. We got up practically over Port-au-Prince, about 6,000-7,000 feet, and I heard this thing, "pop—pop", and I knew we were in trouble of some kind. The last I remember I remember bracing myself, because we were headed down like we were going into a spin, and we landed in the mangrove bushes on the beach at Port-au-Prince. I was completely knocked out. I had a concussion. I awakened and I heard some chopping sound, and I tried to get up out of this seat I was in, and found I couldn't. I noticed something had happened to my left leg, and it turned out I had a compound fracture of both bones of my left leg and of my nose. The noise that I heard were the Marines with their machetes chopping their way in to get us. I was asked if I wanted to go to the Marine hospital or my own, and I said to take me to my own. I was there for a couple of months.

Commander Melhorn: Didn't you have some problems on the operating table with the anesthesiologist?

Admiral Melhorn: They had to give me a general anesthetic to take care of me. They called a medical officer from the Marine hospital to give me the anesthetic, and when he arrived, I saw what shape he was in—he was drunk. I just waved him away; I wouldn't let him touch me. So I called for my own anesthetist—in those days I was doing a little surgery myself.

He was a black man, a Haitian, and a darned good anesthetist, too, so he took over. They put me to sleep and put a cast on, but they didn't put it long enough; they only put it up to my knee and it should have been up to my hip joint, so after about two months, when they took the cast off, I had non-union, it was just like a piece of rubber. I had visions of being sent back to the States and getting a bone graft—sliding graft they called them in those days. Well, they sent a hospital ship in from Guantanamo, the old Solace, and took me to Washington and put me in the naval hospital.

Interview II

In this clip from his 15 February 1970 interview with Commander Etta-Belle Kitchen, USN (Ret.), Commander Melhorn speaks of the action that sank PT-44 off Guadalcanal in 1942.

Commander Melhorn: This was strictly Robert Montgomery in the movies and They Were Expendable sort of thing. But we always idled in with the mufflers down and tried to get into a shooting position. Then when it came time to get out, then we opened the mufflers, then we cranked on the throttles and got out of there at high speed behind smoke. But for the attack phase the watchword was stealth. So we started in behind this action that was swirling on ahead of us up in the sound as this destroyer column tried to punch its way through to the area of Tassafaronga. We were right behind it, and we could see tracers going off in all directions up in front, which meant that they were out there chasing our boats someplace. If you can see the tracer on a shell, you've got a pretty good idea that the shell is not for you because the tracer burns in the rear end of the shell. So we went on in.

Commander Kitchen: You were behind the attacking force?

Commander Melhorn: We were behind the attacking force. We were practically the last ship in the attacking force, but we were waiting until they would make their move to come out to present a broadside to us, and we would be in a good firing position. We were not in a good firing position at the time, because we would have been a stern chase for the torpedoes. So sure enough, finally they began to turn, and we picked this up with the glasses. The quartermaster, as I recall, told Frank, "Captain, your target is on the starboard bow."

And we could see this destroyer making a turn to the right up there which would present us with a good shot. We had passed at this time, a destroyer which had been hit by one of our boats—we actually saw the hit. It was not a burning hit, it was just this great geyser of water that went way up above the mast on this hit, but all very, very silent. We didn't hear a thing. Of course our engines were making a noise, too, which is one of the reasons we didn't hear anything. Then the destroyer fell out of column. It later developed, it was the Teruzuki, which was a brand-new Japanese class of destroyer. We passed her, steamed on by. She was on our starboard hand as we went by. We passed her to pick up the rest of the action, so she was then well astern of us when we made out this first destroyer on our starboard hand crossing from left to right. At the same time I was standing behind the cockpit. There was an arrangement on these particular boats where you had the cockpit, and right behind the cockpit there were two .50-caliber machine guns in scarf ring mounts, side by side. I was standing up with my back resting against the gun mount acting as a lookout, and over on the port side I saw more destroyers suddenly coming in. I said to Frank, "Frank, I think we ought to shift target outboard. Otherwise we're going to be boxed." It was the apparent thing to do. As soon as he saw them, I never would have had to tell him. He was the boat captain, anyway. So we shifted targets. Then suddenly we saw two more even further on our port hand, which meant we were really in a box then, because we were surrounded then on an arc from beam to beam ahead with hostile ships. Just at that moment, the Teruzuki burst into flame astern which made us a complete silhouette, like daylight, and the shells started coming in. So we turned—we had to abort the attack—and turned and started out on high speed. The shelling was extremely heavy. So much so that I can still smell the cordite. The whole air around there was nothing but splashes and cordite. We finally got out of there without a hit, for some reason, and went out under the lee of Savo, and turned again to make another attack. We figured we had gotten clear and they would have to be coming out of there sooner or later. We'd slowed and we were starting in, and just then I saw behind this burning destroyer a muzzle flash and no tracer. Well, when I didn't see the tracer, I figured "that's for us.” "So I jumped down into the cockpit for some reason or other, and I was no sooner in the cockpit than we took a direct hit abaft the .50-caliber scarf ring mounts. This completely wiped out the whole rear end of the PT boat. I can remember looking back to see what was left back there, and it was just a black outline of the hulk with little tongues of flame around a void of what used to be the engines. Having been a battery officer on a destroyer myself, I could just hear that Jap gunnery officer over there knowing that he had his hit, saying, "No change, no change, shift to rapid fire." I knew that things were going to get pretty sticky around there pretty quick. There were figures running toward the bow. Frank Freeland started aft, and he muttered as he went by me something about going to the life raft.

Someone on the bow hollered, "Shall we abandon ship?"

And he said, "Yes." He continued to go aft. I was just standing up there deciding that it was time to go. There were about five of us standing up there in various positions and we hit the water at once. As soon as he said go—we went. I had no sooner hit the water—I dove deep because I just had a feeling something was coming fast—and just about then another salvo hit and hit the tanks. We had torpedoes, depth charges, 2,700 gallons of high-octane gas, because we had expended practically no gasoline—there were maybe 2,000 gallons by then. The whole thing went up together. I was underwater a few yards away—no more than that—and it just paralyzed me. I was wearing a kapok jacket and the jacket took charge and pulled me up to the surface. I came up in a sea of fire. I couldn't move and I figured I was just going to burn to death here, and then suddenly another shell hit and threw up a tremendous splash. The splash came down all around me and put out some of the fire.[1]

Commander Kitchen: Freeland went down with the second . . .

Commander Melhorn: I never saw Frank again, but nobody on that boat would have survived. The biggest piece of the boat was about as big as my finger. It just blew the boat completely apart. There were people in the water. I saw one helmet and I heard some cries from in the flames. These guys were out of it—they were gone.

[1] For a longer description of the same action, also quoted from Melhorn, see Robert J. Bulkley, Jr., At Close Quarters: PT Boats in the United States Navy (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962) , pages 97-99.

About this Volume

Based on one interview with Admiral Melhorn conducted by Etta-Belle Kitchen and Charles Melhorn in February 1970 (77 pages) and one with Commander Melhorn conducted by Etta-Belle Kitchen in February 1970 (76 pages), the volume contains 153 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyright 1983 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewees placed no restrictions on its use.